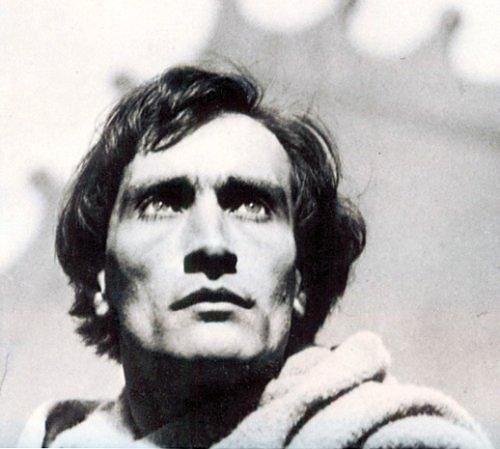

(Celebrated ex-monk Tibetan intellectual Gendun Choepel)

I was recently reading through Donald Lopez’s excellent book “The Madman’s Middle Way’ on the contributions of controversial and brilliant early twentieth century Tibetan intellectual Gendun Choepel (1903-1951), and I came across something I had missed before, namely, Gendun Choepel’s reflections in Tibetan on the popularity of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831-1891) and the nature of her new religious movement Theosophy, as found in his ‘Serki Thangma’ or ‘Field/Surface of Gold’. This travelogue (which has been fully translated into English by Lopez and Thupten Jinpa) constitutes an extensive autobiographical account of the ex-monk’s wanderings in the 1930s and 40s throughout India and then Ceylon/now Sri Lanka. It is chock-full of fascinating insights about British empire, comparative religion, gender, and science as seen through the eyes and experience of an extremely gifted and innovative Tibetan scholar, poet, and artist. Continue reading