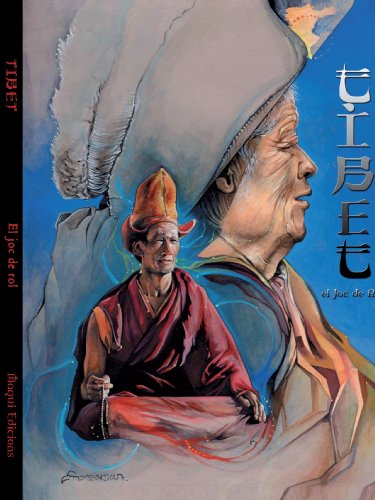

Recently, Brian St. Claire-King, the Creative Director of Vajra Enterprises and creator of Tibet: The Role Playing Game sent me a response to my essay on this blog about his game, and he was kind enough to let me share it with readers. Brian has honoured me with some very thorough and thoughtful comments on my post. I’m glad he responded – I made it very clear to him that what moved me to write the piece in the first place was the extent to which he achieved what struck me as a remarkable level of feasibility in his representations of Tibetan life. I was amazed to discover his work, and at least a few Tibetans who read my article have let me know that they were fascinated to see it too.

In his letter below, Brian answers some of the questions I pose in the article, and points out some areas worth elaborating on or exploring further. He expands persuasively on gaming’s power to engender empathy, and echoes eloquently some of my own thinking on the parallels between anthropological and gaming ‘pedagogies’ (I especially love the idea he mentions of gamers using RPG resources to get into the headspace of the very same Christian moral crusader ‘enemies’ who sought to oppose their activities). Continue reading