I started asking myself the other morning if I could remember when I really felt like I was going to become an academic. I was a precocious child – I was passionate from a young age about reading and learning, about conducting my own research into specialized subjects that interested me. But I found myself thinking just now about when exactly the point of no return might have been.

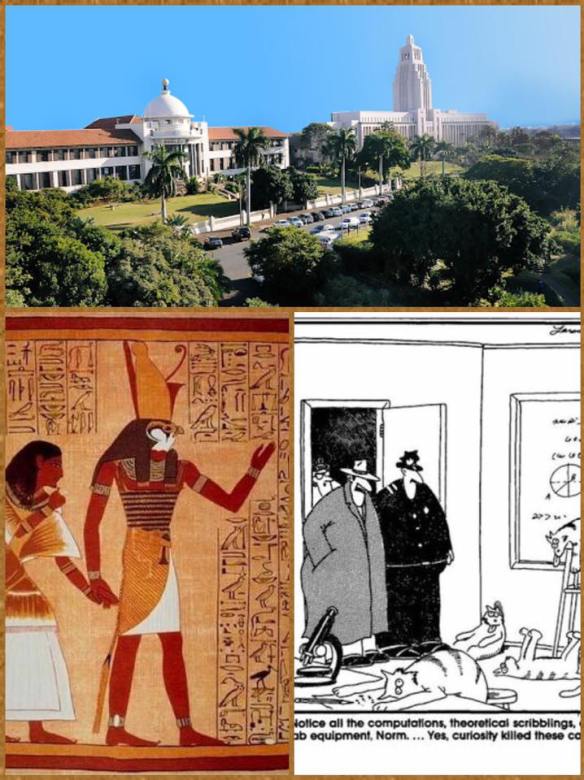

I am the son of a (now semi-retired) professional academic. When I was growing up, I would often visit my Dad’s office in the English Department at the University of KwaZulu Natal in Durban, South Africa. My Dad worked for many decades as a professor there, and the university looms large in the city and my snap-shot memories of it. It is a tall, tan building that looks down somewhat imperiously onto the city from atop a small hill. Pushing up from the folds of land surrounding it, it exudes a quiet constancy. Yet despite its classic monastic-fortress on the hill feel, any firmness it might manage is ultimately lost to Durban’s humid haze, and the city’s trademark red sand has coated the building’s stonework altogether too thoroughly for it to maintain any illusion of celestial stateliness – ruddy-cheeked and dusty, the university’s brand of monasticism is less regal abbot, and more older, disheveled but dignified bachelor – tall, skinny and off to one side, a friend of the hosts at the mixer, pulling nervously at his collar. Continue reading