When I was a kid growing up in pre- and post-Apartheid South Africa it wasn’t easy to study occultism.

To be sure, South Africa is a country filled with professional and semi-professional sorcerers, but it is also a nation whose white supremacist government for a long time directly funded a special ‘Occult-Related Crimes Unit’ attached to the national police force. This unit, which was founded in 1992 and which was supposedly officially disbanded/absorbed in 2006 (but which is in fact still operating in various capacities) was guided for the most part by the expertise and priorities of white, Afrikaner Christian investigators. Working under the auspices of the state, pastors with police training, criminology degrees and a measure of knowledge about local black South African ‘customs and traditions’ investigated South Africa’s dark and criminal occult underbelly. While the existence of witch-lynching and so-called ‘muthi killings’ – ritual murders conducted to ostensibly secure human parts for sale in criminal magical economies and use in rituals – served as the primary justification for state-spending on the Unit, the majority of the Unit’s time appears to have been spent on locating and routing out ‘cells’ of adult and teenage Satanists, and assisting especially young South Africans who had been afflicted by demons and other Satanic forces.

(Dr Kobus Jonker at his desk. The white rock/paper-weight has the Afrikaans translation of Psalm 18:2 engraved on it, “The Lord is my Rock, my Fortress (‘skuilplek’ -‘Hideaway’), my Redeemer”)

A few years ago, Vice Magazine conducted an interview with the former head of the Unit, Christian preacher and homeopath Dr Kobus Jonker. Although the Unit no longer formally exists in the way it once did, Jonker continues to train and consult with the South African Police Services, and act as an expert witness for a range of gruesome and spooky court cases. From the interview, it is clear that Jonker has in recent years learned to moderate his Christian chauvinism. While 2010 Jonker avows that Pagans and Wiccans have ‘nothing to do with Satanism’, and that Heavy Metal does not inevitably lead to Devil Worship, a brief perusal of his earlier expert publications on Satanism and the occult in South Africa reveals a different picture. Certainly, I know more than one South African Pagan or ritual magician who can recount stories of being directly targeted by the Occult Crimes Unit and authorities associated with them (this includes one old friend who was framed for a ‘secret Satanic temple room’ prank that some classmates of his pulled in high school. My ritual magician friend was already known to be involved in occultism, so, although he had nothing to do with dressing up an unused room on the school premises to look like a thriving location for Black Masses, or with anonymously tipping off school authorities about alleged ‘Satanic activity’ in the school, he was subjected to interrogation by Unit representatives and preachers and subsequently expelled).

(Signs that Reveal The Dark Side…or just well, being a moody teenager. A clipping taken from the South African newspaper The Sowetan, 19 March 2013)

As 2010 Jonker explains, South African Satanists are not like their distantly-related ‘philosophical’ LaVeyan Satanist cousins in places like the USA. They are active criminals obsessed with murder, ritual sacrifice, rape, and torture, who are beset by and in league with legions of demons (see here for a document prepared by the South African Pagan Rights Alliance which argues that this latter kind of Satanism is a sensationalized media construct).

Whatever the case, by the mid to late 90s when I was beginning to actively pursue a personal education in Western occultism, shelves devoted to ‘New Age’ ‘Metaphysical’ and ‘Esoterica’ titles had only just began to cautiously appear in major book retailers. I still remember having to ask a very nervous-looking middle-aged Afrikaans woman at CNA, a national South African book and stationary franchise, to retrieve a special key from a backroom to open a locked compartment behind the check-out counter that housed three or so packs of cutesy Tarot cards and about four mass-produced books on astrology and candle magic by American authors. With time and the post-Apartheid’s constitution’s commitment to freedom of religion under inclusive secular democracy, specialty esoteric book and supply stores started to become more feasible and prevalent in the country.

Years ago in Cape Town, after high school ended, I would often walk in my school uniform to one specialist retailer called ‘Wizards’ bookstore. Wizards books sold New Age, Pagan, Occult, Ritual Magic, Alternative Healing, and Conspiracy Theory/Alternative History literature. I was a regular, and the women behind its counters were (somewhat) less nervous than the auntie in CNA, especially after they read a column I used to write at fifteen on Western esotericism in one of the New Age magazines they sold for a while. It still felt weird being in there in a recognizable school uniform but I had their respect and respected them in kind.

(A special event for ‘Free Comic Book Day’ held outside Wizards Warehouse store in Cape Town, South Africa in 2011)

What I had less respect for then was the other half of the store. For Wizards was not only a purveyor of esoterica, but also a Role Playing Gaming hub. The shop sold RPG packs and accessories alongside translations of 16th century ritual magic texts, instructional manuals on Taoist inner alchemy, and indigenous Hawaiian shamanism. Tarot cards sat next to Magic the Gathering decks. Fellow high-schoolers competed in gaming tournaments at tables outside.

I found the whole thing quite embarrassing. I was not really a gamer, although I had friends who were. My sister and I played MTG once, but I’d never (and have still not) played any off-computer table-top Role Playing Games, the kind with character sheets and dice. I did what I could to avoid RPG sections and fans while at Wizards. The few specialty occult dealers I’d visited before did not double-up in this way. For me magic was not a past-time or a game. Sure, ‘pop occultism’ and ‘mainstream Paganism’, like Role Playing Gaming, had its associated demographics and aesthetics, but for me magic was predominantly private and internal – what mattered most was personal transformation and insight. Study, practice, and hard work were everything. Teenage me saved up for new books, read and practiced rituals and meditations in my room and in other locations almost every day. I didn’t want to be associated with RPG-ers. Like me, they were often nerdy misfits fascinated by history, cross-cultural experience, and the arcane and esoteric, but I resented their presence at the store all same. For them, magic and spirits were recreational and imaginary, for me they felt all too real and challenging.

My feelings about the popularisation of occultism were mixed. On the one hand, I was happy when others acknowledged esoteric knowledge’s worth. Yet I also resented that these RPG-ers mined material for their fantasy world-building from what I thought of as the unfairly rejected and infinitely profound treasure-trove of esoteric traditions. In his earlier satanicky-panicky materials, Dr Jonker suggested that even if RPGers denied any active belief or interest in the occult, games like Dungeons and Dragons were a gateway into absolutely real and absolutely deadly diabolism. It was even more aggravating then when, in response to these demonizing claims, I would hear South African RPGers respond that magic or esoteric disciplines were just a bit of fun, historical and intellectual curiosities that didn’t really work or couldn’t really do anything, good or bad. Whether I liked it or not, esotericism and RPG culture occupied overlapping social and economic spaces in early 21st century South Africa.

Playing the Game of Tibet: ‘Accurate’ historical fiction, ethnography, and the imagined other

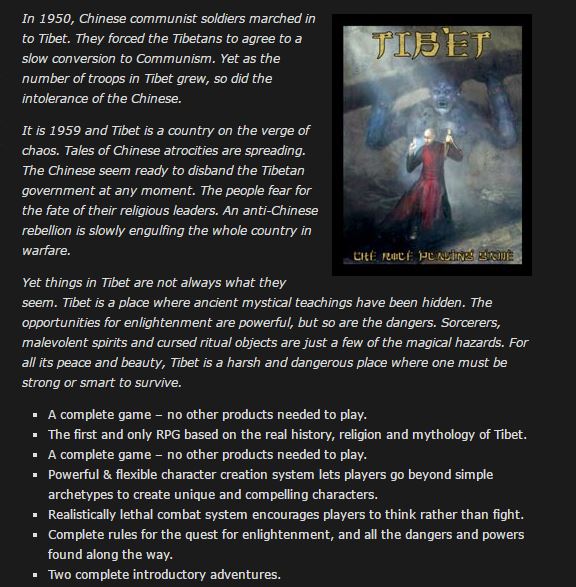

Specifically, what I was feeling, what bugged snobby teen-occultist me, was the politics and ends of knowledge production and re-production, and had to do with, in a word, jurisdiction. Just a few days ago, I found something very interesting online, quite by accident. This something has got me thinking very hard indeed about the politics and social lives of expert knowledge production, about this idea of jurisdiction. It also ties in neatly with my recent reflections on here about imagined versus actual experience in relation to Tibetan cultural life. What I found was an RPG called Tibet. This Role Playing Game is the brain-child of writer Brian St. Claire-King, who published it in 2004 through Vajra Enterprises, the publishing company he founded three years before that in Oregon, USA. ‘Tibet’ is billed as “the first and only RPG based on the real history, religion and mythology of Tibet”. The game is set in Tibet of 1959, just prior to the (real-world history) crushed Tibetan uprising against communist Chinese occupation that saw the Dalai Lama and tens of thousands of Tibetans flee the country into exile.

Players of Tibet are able to chose from a list of 26 Principal Characters, with varying overlapping and unique skills and capacities (as it happens, you can do an online quiz here to determine which of these best suits your own temperament. I got ‘Kagyupa monk-yogi’ and ‘White Robe’ non-celibate yogi. Funny, huh?).

Aristocrats

Ascetics

Astrologers

Bonpo priests

Craftpeoples

Dob Dobs

(Traditional Tibetan) doctors

Farmers

Foreigners

Gesar bards

Kagyupa monks

Merchants

Mirror-gazers

Nomads

Nyingmapa monks

Oracles

Revenants

Sakyapa monks

Savages

Sorcerors

Treasure-finders

Unclean (professions/social classes)

Weather-makers

White-robes (non-celibate yogis)

Yellow-hat sect monks

(For a fuller break-down on these options, see the video here). All of these categories are actual Tibetan ones, and many of them point to religious and socio-cultural roles which I have written about on this blog. For example, the mirror-gazer diviners to which St. Claire-King refers are often called pra phab pa in Tibetan, and use special polished surfaces, like brass ritual mirrors, sword metal, or finger nails, to see visions that are produced by familiar spirits known as pra. These practitioners obtain one of these spirits and hone their capacities to see them clairvoyantly by engaging in special mantra recitation and visualization retreats, through which different meditational goddesses bestow pra from their retinues. There are different pra associated with different natural spheres and elements. The ‘revenants’ in the above list describe ‘das log or shi log pa, people, overwhelmingly women, who die briefly, experience visions of the after-life and other worlds and then return to life to tell others of what they saw. They often function as diviners and other sorts of religious specialists following their experiences.

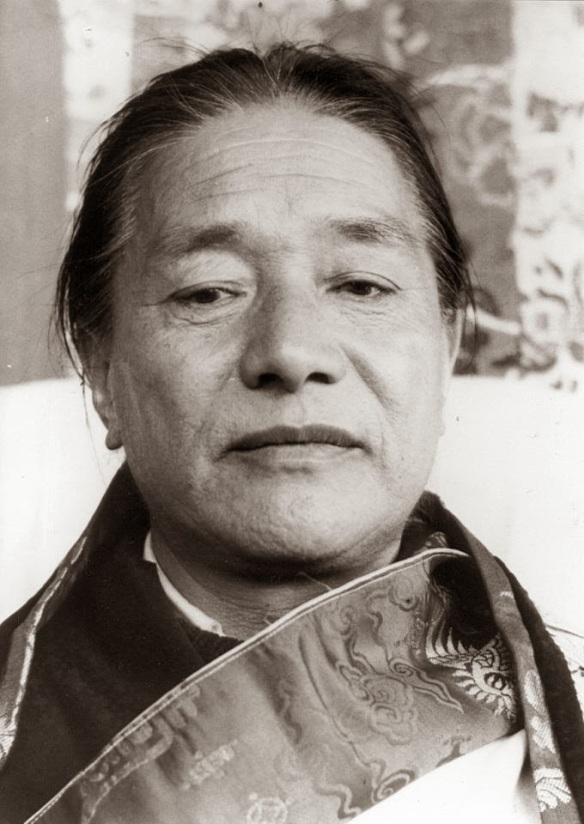

(The great Tibetan master Dudjom (‘Demon-Conquering’) Rinpoche, Jigdral Yeshe Dorje, 1904-1987)

Tibet’s four major religious schools are represented in St. Claire-King’s list along with Tibet’s pre-Buddhist state religion Bon. Adherents of each of these categories are described as ‘monks’. The RPG format demands discrete classes or careers for player characters, and St. Claire-King’s list includes a number of distinct categories which in actual Tibetan life would most likely to be enshrined in a single person. For example, Dudjom Rinpoche, the Great Tibetan non-celibate tantric master or ngakpa who served as the first head of the Nyingma sect in exile was, among many other things: an Aristocrat involved in politics; someone who spent many years of his life practicing in retreat as an Ascetic; versed in Astrology; a traditional Craftsman, a capable Sorceror (although not a criminal, money-hungry mercenary one like the gaming info describes); a Treasure-Finder, or celebrated visionary prophet and revealer of hidden teachings; someone who knew how to conduct rituals as a Weather-maker; a White-Robe yogi skilled in initiated tantric yoga; and a Nyingmapa, albeit a married, non-celibate one and not a monk.

The constraints of Tibet’s design and architecture as an RPG would thus seem to foreclose the possibility that the game could ever provide a fair representation of the nuances of Tibetan cultural and religious history and identity. And yet, the two ‘authoritative’ ethnographic precis which I gave above about pra phab pa and ‘das log were not particularly different, or better or worse, than St. Claire-King’s own various factoids in his gaming manual and videos. Indeed, it’s not unthinkable at all that something like the following summary which St. Claire-King provides about Tibetan cosmology and magic could appear as a footnote in an anthropological or Tibetan Studies monograph:

“Magic- When the supernatural is encountered in Tibet, it is rarely visible. Instead, the majority of supernatural happenings are invisible and intangible. They can only be sensed by the clues they leave in human lives. The use of magical knowledge to determine exactly what is happening in this invisible world is very important. For instance, a string of misfortunes could be from a curse, an infestation by malevolent spirits, a minor deity who has been inadvertently offended, bad karma from a previous life resurfacing, etc. Tibetans believe in and use a variety of magic [sic]. Astrology and many forms of divination, simple and complex, are used to predict the future and gain clues about the supernatural. Holy charms (items which have absorbed good karma) cause good luck and keep malevolent spirits away. Sorcery releases the bad karma in certain items to cause illness, poor luck, bad weather and attacks by malevolent spirits. Sorcery is feared and practitioners are often banished. Magic to control weather is highly valued and taught in many monasteries. Exorcism and control of malevolent spirits is very important to Tibetans. Mantras (spoken and written prayers), thread crosses (devices that trap spirits) and gluds (dough facsimiles of humans) are used by monks and other magical practitioners to ward off, trap or dispel malevolent spirits. Sorcerers use these same devices to attract, capture and send malevolent spirits. The major Buddhist sects know complex, secret rituals that will end a person’s life, yet try to use them only when it is a compassionate act.”

Here is a Level 1 game scenario/sample adventure, called ‘Saving Denver’. As much as it sounds like it might be about vanquishing Colorado cannabis gentrification, it is actually about black magic and the CIA:

“This is a short adventure, suitable for level 1 characters and beginning players. The adventure starts with a mystery: an entire monastery slaughtered by a supernatural force. PCs must track an escaped cursed phurba [the Tibetan word for a three-edged exorcistic ritual dagger] to a nomad rebel camp, where it waits on a CIA plane to be flown to America. If it reaches America, where divination and exorcism is unknown, it will wreak incredible havoc.”

Another sample adventure given on the Vajra Enterprises website directly touches on issues relating to the upholding of vows and ‘real’ versus virtual sex in the context of tantric Buddhism that I touched on in my last two posts, here and here. In a story dubbed ‘The Handsome Monk’ we read that:

“In Brief- The PCs will have to save a young monk who is torn between a love spell that will drive him insane if he doesn’t have sex and a dharmapala [a fierce Buddhist deity that protects the Buddhist teachings and punishes oath-breakers] who will kill him if he breaks his vow of celibacy.”

A jealous Tibetan sorceror has cursed this young monk to be mad with lust for his own wife, who he wants to test for some reason. The monk resists and takes himself off to a cave, the wife is so moved by his moral fortitude and stoic suffering she actually falls in love with him. We read:

“Lobsang’s Dilemma- Lobsang is half-insane when they get to him, and despite his constant attempts to meditate he has been suffering so badly that his Karma has been going down. If were to die right now (in a non-painful way) he would probably achieve a human afterlife (especially if someone does the Bardo rites) but if he goes on suffering for much longer he won’t even be able to be a human again in the next life. Lobsang will submit to a painless death if he is told it is the only way to end his suffering.

Beyond a miracle, there is no cure for the curse that does not involve sexual contact between Lobsang and Nyima. If Lobsang has sex with Nyima (it won’t be too hard to convince him to do this) then the dharmapala Nagapka will immediately set upon Lobsang and try to destroy him. If the PCs are skilled exorcists they may be able to drive off Nagapka (a temporary solution) or even destroy him.

Another solution lies in the grey area between what is considered sex by the curse and what is considered sex under the vow Lobsang took. Some Dobdobs think that having sex between the clenched thighs of other monks does not count as intercourse because no orifices are entered and thus does not violate their vows of celibacy. Anything which provides sexual release for Lobsang and involves the flesh of Nyima will end the curse. The problem with finding such a ‘loophole’ is that the dharmapala has to be convinced that Lobsang has not violated his vows. Oratory, Logic or Tibetan Law skills will be very useful in this regard, otherwise the PCs will have to make their case and hope for a good CHM roll. Treating the dharmapala with respect (the Etiquette skill is useful here) will help the PCs win over the dharmapala.”

Lurid as these seem, the idea of CIA intervention in Tibetan rebellion without a proper understanding of internal Tibetan political and cultural dynamics is certainly not out of keeping with actual Tibetan history, and more than one Tibetan practitioner has struggled with major binds involving hyper-zealous and wrathful protectors. In addition to an essay comparing the aesthetic of Vajrayana tantric Buddhism to that of Gothic fiction and sub-cultures, St. Claire-King also offers a handy chart of quick comparisons between 1959 Tibet and USA. The two nations are compared in terms of everything from political and economic systems, and crime to ‘animal rights’, religious and pet cultures, to ideas about marriage and violence. The chart is naturally filled with all sorts of cultural essentialism, generalizing, and de-contextualized claims, but I would be lying if I said that I hadn’t seen similar such lists in assigned International Relations university textbooks that look considerably worse.

Writing Role Playing Games and writing ethnographic monographs is obviously a very different exercise. It seems that much of St. Claire-King’s sources are secondary – Tibetan terms are mispronounced often enough in his videos to suggest that his material was not designed in conversation with native Tibetans, or with anyone more accustomed with Tibetan language. St. Claire-King’s work is not ethnography but it is considerably ethnographically-informed. What does this mean? It means that St. Claire-King has drawn on ethnographic sources (academic descriptions by scholars, Tibetan and non-Tibetan, about Tibetan history and ways of life). His game factors into its design and dice-roll point-system Buddhist ideas of karma, positive merit, enlightenment, and samsaric attachments. It works hard to make everything from its names, to its vocations, settings, historical references, spiritual forces as ‘authentically Tibetan’ as possible.

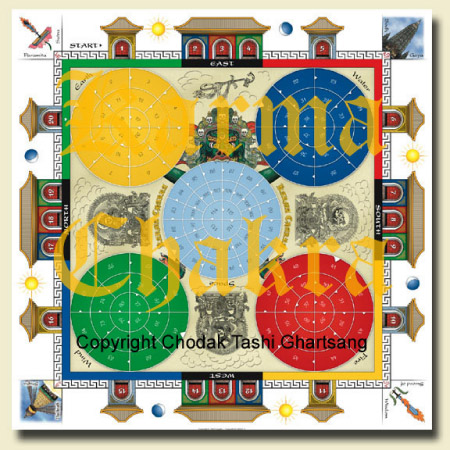

(Karma Chakra, ‘The Wheel of Action’, a Buddhist board-game by Chodak Tashi Ghartsang)

But authentic for whom, exactly? It’s unclear whether St. Claire-King ever imagined that actual Tibetans might play his game. RPGers playing ‘Tibet’ may appreciate the attention to detail, but one is left wondering what opportunities (or incentives) exist for them to check St. Claire-King’s sources and claims. Many gamers who come to his game will most likely have played a host of other table-top RPGs already, some of which might have been works of historical fiction, others far more fantastical, and less committed to historical accuracy. One wonders how much historical accuracy is a priority over game play and design for consumers. Indeed, one reviewer of the game suggests that (aside from arguments in gaming forums about whether the depiction of the Chinese in the game was racist) one of the main issues that could be taken with the game was that the focus on the 1959 political and historical realities of Tibet felt dissonant with the more spiritual or ‘mythological’ aspects of the game.

That players could separate out the ‘mythological’ or ‘cosmological’ dimensions from ‘historical’ or ‘political’ ones is interesting in itself. The board-game Karma Chakra, another game inspired by Tibetan religious and cultural life, offers an interesting comparative case. This table-top game was designed by Canadian Tibetan Chodrak Tashi Ghartsang, and was devised with “Buddhist education” primarily in mind. The game is described as being “based on Buddhism Mahayana & Vajrayana Buddhism in particular” and as offering an introduction to “complex Buddhist subjects through a simple-to-understand style. It gives players his/her own freedom to visualize, imagine, think & discuss about Buddhism at many different levels.” We learn further that Karma Chakra is:

“…a very informative and intellectual game that has the potential to generate interesting and serious discussions and dialogue among the students. At the same time, it is a fun and exciting way to learn about Buddhist tradition, culture, history, art, ethics, principle and philosophy. Karma Chakra deals in numerous Buddhist doctrines & traditions such as the Sutrayana tradition of Theravada and Bodhisattvayana; Lamrim, Lamdre (Gradual path to enlightenment), Terma (hidden treasures) and Mantrayana (Mantra vehicle) tradition of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism.”

Like St. Claire-King’s game, Karma Chakra incorporates ideas from Tibetan cosmologies into its game-play, and notions of karma and spiritual progress are foundational to its design. The game, meant for 2 to 4 players, includes Sonam Cards (merit cards), Terma Text (treasure text), Tashi Cards (auspicious cards), and Mara cards (evil cards). In his letter of support for Karma Chakra, Thubten Jinpa, prominent Tibetan scholar and the Dalai Lama’s chief translator, explicitly compares the game to RPG table-top games like Dungeons and Dragons that seek to immerse players in an imaginative experience of what it would be like to be in another world:

“Literally meaning “the wheel of karma,” Karma Chakra takes the players on a tour de force of both the exotic and esoteric dimensions of the Tibetan Buddhist world. Blending myths, history, philosophy and the moral theory of karma, the game mimicks the experience of what it would be like to live in the Tibetan Buddhist world, echoing the influential Dungeons and Dragons game.”

Thubten Jinpa-la suggests that the game will be of benefit to students of Buddhism, and to young Tibetans living outside of predominantly Tibetan societies. He describes his positive experience playing the game with his own daughters in the USA:

“Karma Chakra will be especially valuable to those who wish to learn something about the Tibetan Buddhist world in an “experiential” way. It will be particularly welcomed by thousands of Buddhists of Asian origin who today live in multicultural societies, such as Canada and the United States, and wish to teach their children something valuable of their own traditional culture. I, for one, have great fun playing this game with my two young daughters with the awareness that, at the end of the game, my girls would have become more familiar with my own Buddhist tradition and Tibetan culture.”

From the Armchair to the Table-Top? Hobbyist occultists/ethnographers versus engaged sorcerers and fieldworkers

There is something uncomfortable about the idea of a room of predominantly non-Tibetans imagining themselves as Tibetans for entertainment. In a 2009 essay anthropologist Abraham Zablocki discusses patterns of Westerners using and consuming Tibetan culture “in order to participate in, and establish affinity with, the special qualities which Tibetans are presumed to have: such as being holy, exotic, or premodern.” Specifically, in his piece, he focuses on “one quite distinctive object of appropriation, that of Tibetan identity itself.” Discussing what he calls cases of “tulku envy”, where Westerners struggle to have themselves or their children recognized as Tibetan Buddhist reincarnate lamas, Abe notes how such “would-be reincarnates are not so much striving to establish their affinity and sympathy with Tibetan culture, as much as they want to be Tibetan. This raises challenging issues about the nature of cultural appropriation, cross- cultural borrowing, and religious change.”

One way of looking at St. Claire-King’s game might be to see it as a form of appropriation: indigenous Tibetan histories, knowledge, and experiences become fodder for outsiders to play out their fantasies, far removed from the realities of Tibetan lives. Tibetans alive today actually lived through the political tumult of 1959; all Tibetans’ lives continue to be shaped by Chinese colonialism. They can’t walk away, discard an assumed Tibetan name, and carry on with different lives after the high adventure is over. And yet, St. Claire-King clearly cares about the specificities of Tibet, cares about getting the details right, which suggests that he, despite not having a primary Tibetan audience in mind, like Chodrak Tashi Ghartsang, is concerned with education as well as entertainment. RPG creators are analogous to anthropologists and ethnographers in that they are imagining cultural worlds and how actors in those worlds would act based on prevailing structures and constraints. Indeed, in this earlier post, I pointed out the possible parallels between fantasy-entertainment like Game of Thrones and the knowledge that anthropologists’ produce, and there’s even an online quiz you can take which will test to see how effectively you can differentiate titles of anthropologists’ ethnographic monographs from names of Xena: Warrior Princess episodes.

Still, while anthropologists also create narratives and representations about how individuals in particular cultural worlds puzzle through their options and constraints so as to act on, through, and in spite of those worlds, these representations are based on fieldwork. Their research involves actually being present in and a part of the worlds they come to theorize and partially and imperfectly represent. It implies embodied and extended engagements with living and breathing individuals to whom researchers are accountable, whether they want to be or not. Ethnographic fieldwork requires keeping one’s positionality and personal histories in mind – these cannot be erased or suspended as part of immersion in other worlds. The ethnographer’s own changing body, life, and experiences are their primary barometer, their ultimate research instrument. Though some ethnographers might try, they also cannot simply get up from the table and walk away from the worlds and communities with which they have become intertwined. The ‘attachment’ and ‘karma’ points ethnographers earn by engaging with real people’s lives are difficult if not impossible to erase.

When we ask first-year students in our socio-cultural anthropology classes to read ethnographies about frequently unfamiliar and incredible ways of life and being, we too want them to have the chance and personal freedom, as with Tashi Ghartsang’s Karma Chakra, ‘to visualize, imagine, think & discuss about [different life-worlds] at many different levels.” Ideas of imaginative immersion, suspension of disbelief, and acting and thinking ‘what’ and ‘as if’ have been central to the discipline of anthropology, and the social sciences more broadly. Tibetologist Frances Garrett has used Karma Chakra as an educational aid in her lectures on Buddhism and Tibetan culture, and students of historian Mikki Brock at Washington and Lee University turned witch-hunts in 17th France into a choose-your-own-adventure game as part of their classwork.

Imaginative engagement and play can fuel empathy, insight and personal and social transformation. As author and activist Adrienne Maree Brown has noted, all social organizing counts as science/speculative fiction. As she puts it, “trying to create a world that we’ve never experienced and never seen is a science-fictional activity. And, to get to a world where there is no rape, no homelessness, no inequality, is going to require a good amount of future casting and future thinking, aligning ourselves into the future, exploring and playing with how we’re going to get there.” On the other hand, the RPG world has also gained a certain reputation as a space where racist, misogynist, homophobic, and transphobic tendencies reign supreme. As Victoria Cooper has shown with her research on the role played by the idea of the ‘Medieval’ for certain fantasy video gamers, imaginative gaming worlds can become mediums through which to re-imagine real-world histories, and justify and promote hyper-nationalist, hyper-conservative values and positions. The alternative worlds of gaming can thus provide spaces for both the re-inscription and justification of prejudice and exclusionary forms of belonging, and also open up arenas for re-imagining selves and community. The comedy series Community brilliantly captured RPGs’ dual potential to become spaces for inclusion and tolerance AND inequality and brutalization in its episode ‘Advanced Dungeons and Dragons’. Here’s a fan-made trailer for the episode that gives some idea:

(See this post too, for some extensive reflections on misogyny, racism, and rape culture in gaming worlds).

However different writing and playing RPGs may be from producing anthropological knowledge or engaging in ethnographic fieldwork, Tibet: The Role Playing Game, encourages us to think about broader questions about imagination, difference, and the social lives and histories of ethnographic knowledge production. Scholars of Paganism, Witchcraft, and Western Esotericism have made clear the extent to which ethnographic, folkloric, and historical materials have served as important inspiration for contemporary practitioners or as support for claims about esoteric histories and traditions (archaeologist and neo-shaman Robert J. Wallis in particular has devoted his career to investigating the overlaps and tensions between professional archaeologists’ expertise and claims and those of neo-Pagans who have their own relationships with ancient sites and material remains). It has always amazed me too, how little Dr. Jonker has acknowledged that he and his own work may in fact generate Satanic activity. Dr Jonker seems to have rarely if ever allowed for the possibility that the expert knowledge he himself produces about Satanism in South Africa – through his books, frequent interviews and TV appearances etc – may have served as primary source material for new generations of teenage Satanists in the country – may have in fact helped produce the cultures of diabolism which he has devoted his life to sniffing out and opposing (I’m reminded here of the way that Reginald Scot’s 1584 anti-witchcraft tract The Discoverie of Witchcraft, which exposed and refuted demonic magical practices, ended up becoming a sort of manual for the practice of sorcery itself).

(Dr. Kobus ‘Donker’ (Dark) Jonker, expert in ‘the occults’. The Afrikaans question above the presentation date asks “What God do you worship?”)

Jurisdictional issues would seem to be inevitable when it comes to the production of knowledge about esotericism. Time and time again, ‘agnostic’ scholars of magic and esotericism have described being either positioned as magic-workers themselves or actually becoming practitioners as a result of their research (For classic ethnographic examples of this trend, see here, here, here, here, and, here). As Jonker and his ilk would say about Dungeons and Dragons, imaginative engagement with ‘spiritual’ and occult ideas is a generative, transformational activity. In this take on things, images and ideas have their own agency and living potency, are responsive. Jurisdictional and category blurriness plays an important part in Joseph Laycock’s new book on the moral panic around Dungeons and Dragons that was aggressively promoted by the Christian Right in the 80s. Laycock suggests that fantasy role-playing games and religion share a great many functions, and that religion “as a socially constructed world of shared meaning—can also be compared to a fantasy role-playing game”. He notes how the fantastical crusades of conservative Christian ‘moral entrepreneurs’ frequently resembled the Dungeons and Dragons universes to which they were so opposed. In combating the evils of the imagination, such Christian moralists “preserved the taken-for-granted status of their own socially constructed reality” and failed to appreciate that they were also engaged in games of world-building, in the forging of collective socio-cultural, moral imaginaries.

The idea that cultural and religious practices can be thought of as ‘serious games’ has enjoyed a certain currency in religious and ritual studies in particular. As humans, we are all equally engaged in different games of our own making, games which we take very seriously. This perspective undoubtedly has some methodological/theoretical utility, not to mention important cultural and philosophical implications and meaning (in the advanced meditation tradition traditions of Tibetan Dzogchen or Great Perfection, for example, practitioners are advised to look upon all that arises like ‘an old man watching children play’. Recognizing the relative, impermanent and ultimately empty and already self-liberated nature of all things, the Dzogchen practitioner develops a kind of relaxed and ironic detachment to appearances, a humorous flexibility and openness that dissolves fixation, and yet still leaves room for enjoyment in the unfolding ‘play’ of reality). Still, the heavy relativism of this kind of scholarly position may have little appeal or meaning for the actual ‘players’ that scholars are studying, and such a take can often provide researchers with limited resources for addressing larger historical or political realities, for considering how it is that certain games do indeed come to be more important, more ‘material’ than others.

Tibet and Karma Chakra’s intended audiences, and the subjectivities, priorities and historical contingencies that lead to their production differ considerably. And yet they raise important ideas about imaginative engagement, and the relationship between knowledge and identity, with which I began this piece. It will be interesting to discover if any Tibetans have ever played, or ever will play St. Claire-King’s game, and to learn more about how they might adjust and rework it to better match their own experiences and priorities. It is my hope that St. Claire-King will do me the honour of reading this piece, and that further insights and discussion can unfold. As it stands, Tibetan writers like Jamyang Norbu have already experimented with re-imagining such classic sciency-fiction worlds as those of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes in intriguingly subversive and post-colonial ways. I have said very little in this piece about existing anthropological research on gaming, but I hope that researchers more capable than me will make some good connections. It will be interesting as well to see how anthropologists find new ways to explore the imagination and imaginative engagement both theoretically and ethnographically, and as part of pedagogies in the classroom.

- P.s. In a nice connection with my discussion of H.P. Lovecraft inspired occultism and the ‘alienation’ of Tibetan religious culture here, it turns out that there also exists a supplement for popular Lovecraftian Role Playing Game ‘Call of Cthulhu’ which is set in Tibet. In ‘Secrets of Tibet’, Tibet’s demons are re-cast as unspeakably ancient and horrifying alien-gods. Considering that Lovecraft himself re-purposed Tibetan culture and popular fantasies about the country for his fictional mythos, this should come as no surprise:

“Secrets of Tibet details information about everyday life in this mysterious and unique country, from the early twentieth century through to more modern times, along with horrific underlying truths. Tibetan demons are remnants of races that came to Earth from the stars millions of years ago. They dwell in hidden places, are served by loyal minions, and are protected by ancient dark cults that span the globe. They slumber until a time when the stars align, and their awakening shall herald the end of the world as we know it. Over millennia some have awakened briefly, sometimes for years or even centuries, to observe what has been happening in the world. Others are dreamers with lesser abilities, but in their slumber they influence the cold mountain areas of Tibet. Combined, their powers have thinned the barriers between the Waking World, Earth’s Dreamlands, and other worlds and dimensions of space and time.

Included within these pages are a history of Tibet, chapters detailing its culture and religion, a bestiary of Tibetan gods and monsters, a guide to the Forbidden City of Lhasa including maps, and three scenarios that will take investigators to the Tibetan plateau and beyond.”

Pingback: Demon Directories: On Listing and Living with Tibetan Worldly Spirits | A Perfumed Skull

Pingback: Shifty Sorcerers and Playing with Empathy: a response from the creator of Tibet: The Role Playing Game | A Perfumed Skull

Pingback: ‘The Truth’: Sins of the Fathers, or what U.S. Network TV wants you to know about Post-Apartheid South Africa | A Perfumed Skull