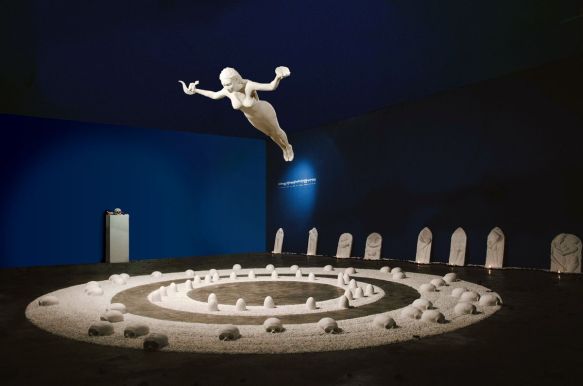

(Crushed marble sculptural installation ‘Flying Dakini’ 2014, by artist Agnes Arellano)

The other day I got sucked into a Facebook comment thread which got me thinking about the connection between translation strategies and the ways that practitioners think about and actually practice religious texts. To give you a little context, the thread was about spirit conjuration procedures and offering practices as found in Western magical traditions, and as the discussion unfolded I found myself reflecting upon the way that certain key technical terms often found in Tibetan sadhanas or tantric ritual manuals have been translated into English.

Translation is a double-edged process – to translate a thing involves both drawing it near and holding it apart. Depending on the circumstances, understanding can arise as much from domesticating a term in a target language as it can from choosing to hold onto a word’s strangeness through a literal translation. What is lost and gained, for example, when we translate the Sanskrit Dakini/Tibetan Khandroma – a tantric goddess – with a loaded Judeo-Christian-Islamic term like angel, and what is obscured, what is illuminated when we opt for say, a literal translation of the Tibetan term (khandroma, mkha’ ‘gro ma) ‘female sky-goer’? While the Hebrew term for angel is cognate with the word for ‘king’ in that language, and calls attention to the idea of spirit hierarchies and heavenly authority, the Greek translation of the term means ‘a messenger’ and points to function over status. Calling a Dakini an ‘angel’ successfully captures many of the very real celestial, tutelary, epiphanic, helping-spirit qualities of these beings, yet it also domesticates the word for readers raised in Judeo-Christian environments to a dangerous degree. In Tibetan language and religion the pristine and primordial nature of mind is routinely likened to the clear expanse of the sky – for a dakini to move through and be of the sky then points to something more than just the fact of her being a flying spirit. And what if we were to complicate things further and follow Theosophist Evan-Wentz’s example and call a Dakini a fairy instead of an angel? Just like Dakinis, fairies are known for their dancing, and can also assume forms both fair and foul. Their association with caves and untamed features of the landscape, their amorous advances towards humans fit well with the Tibetan context, and yet Dakini does not necessarily carry the same pagan baggage as fairy does, and neither fairy nor angel quite captures the way that Dakini can refer to a subtle spirit, a cosmological principle, and an actual physical person all at once.

The particular terminology that engaged me in the Facebook thread, however, had to do not with spirits themselves, but with methods for calling them to be present. One standard feature of Tibetan tantric sadhanas that typically appears early on in the ritual process and which involves the summoning of Buddhas, deities and spirits is the jendren (spyan ‘dren) or ‘invitation’ (also sometimes ‘invocation’) stage of the ritual procedure. The English rendering ‘invitation’ is absolutely appropriate here – jendren is used commonly enough outside of ritual contexts to refer to invitations to attend events and gatherings after all. Still, the thread I mentioned which was all about methods of spirit conjuration in Western magical traditions got me thinking about what would happen if translators of Tibetan opted to routinely translate jendren with ‘conjure’ or ‘conjuration’ instead. For the last seven centuries at least conjure has possessed a distinctly magical connotation in the English language. Deriving from the Latin con + iurare, ‘to mutually swear an oath, to swear an oath together’, while the word once held additional associations of conspiracy (i.e. groups of people secretively vowing to do shady things together), the most durable sense of the word has been that of a magician or ritual specialist calling forth things into being or appearance, or more technically, of a sorcerer extracting oaths or vows and securing agreements from spirits as part of a magical contract or working relationship.

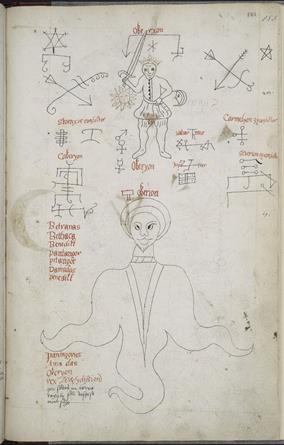

(A page from the important ritual magic miscellany ‘Book of Magic, with Instructions for Invoking Spirits, etc., 1577-1583, from the Folger Shakespeare Library MS. V.b.26. Here depicted is Oberion/Oberyon the Fairy King)

Given conjure’s longstanding association with the formal mechanics of ritual magic in Western contexts, at the very least, choosing to translate jendren as conjuration would open up a space for comparing and contrasting tantric Buddhist ceremony with magical procedures as found in broadly Judeo-Christian-Islamic magical material. One can certainly make a compelling argument for using ‘conjuration’ in place of invitation. The genre of protector spirit sadhanas, for example, or what are known as kang so or expiation prayers in Tibetan tantric Buddhism (bskang gso, ‘the fulfilling and restoring of vows’) explicitly circle around the performative re-articulation and re-affirmation of binding pledges or oaths between human and non-human persons. The tantric practitioner, as part of her own commitment to upholding her religious vows, makes pleasing offerings to those spirits who are themselves oath-bound to protect the integrity of these ceremonial promises. Here human and non-human practitioner mirror and re-confirm one another in mutual inter-dependence, and the ‘con’ in conjuration is clear – the human practitioner makes offerings to the spirits to appease them and to seek reparation for any lapses in their upholding of these pledges as humans, and at the same time, in performing these prayers, she checks and reminds the spirit/s of their own vows, of their own obligations and relationships. This process is understood to ‘fulfil’ or ‘satisfy’ human and spirit co-ritualist (both additional senses of the term bskang) in equal measure – both in the sense of the terms of a contract being fulfilled and of a guest and host being pleased and satiated following a well-executed feast or party. As with some of the Western magical material too, the initial conjuring or invitation of the spirits also often involves ritual commemoration. This amounts to a liturgical recounting of the spirit’s own biography or origin story, what could be thought of as a ritual reminder of the being’s ‘employment history’ – of those promises which were exacted by model mythic figures in the past and are the reason the spirit continues to be called upon today.

Take for example these lines from this invitation or conjuration of the Dharma-Protector Tsiu Marpo (‘The Little Red Rat’) as found in the revealed scripture cycle of the Yuthok Nyingthik (for some historical background on this fascinating deity see this excellent survey by my friend and colleague Chris Bell). The ritualist calls to the protector-deity and produces successive visualizations or emanations of the spirit’s various abodes. As the liturgy progresses an oblique history of the spirit’s own movements, displacements and progressive Buddhicization is sketched out and an indirect but powerful ritual commemoration of the conquests and contracts which brought the spirit from neighbouring territories to its place in Tibet is enacted:

(The King of Martial Tsen Spirits, the Little Red Rat, Tsiu Marpo)

The Invitation:

From the HUNG syllable in my heart light rays emanate,

From the Northern realm of fierce tsen spirits Zangthang Marpo, ‘The Red-Coloured Plain of Copper,’

From the inconceivable cathedral spontaneously realized,

From the retreat-center of Batahor,

From the murky willow grove of Khotan,

From the thirty-three abodes of the deities,

From the Dakini Realm of Oddiyana,

From the Chinese/Indian region where birds take to the sky startled

From the sacred-abode of the omnipresent Vajra

I invite you to this place this instant

O Tsiu Marwa, The Little Red Rat, King of the Tsen spirits

Along with all your battalions and retinues and your group of eight Spirit-Lords who rule over the haughty, unruly spirits!

As someone with a background in Western esotericism and magical traditions, parallels between ritual procedures in Indo-Tibetan sadhanas and say, the Solomonic grimoires and the Greek Magical Papyri, have long been apparent and of interest to me. That said, as I’ve mentioned before here and here, detailed and critical comparative research along these lines remains minimal. Part of this is probably a result of specialized scholarly interests and regrettably rigid disciplinary boundaries in academia. Still, considering how many practitioners and scholar-practitioners of Vajrayana are at least passingly familiar, if not actively involved with Western esoteric traditions, this lacuna is especially remarkable. I suspect that it might also have something to do with the intellectual genealogies that have shaped the formal field of Buddhist Studies in the West. Put differently, there are very specific historical reasons why describing tantric Buddhism as a ‘magical’ system can be a fraught exercise and can elicit alarmed reactions (I’m reminded of a story told to me by a colleague about how once while teaching an undergrad anthropology class he referred to a Tibetan mantra used for making rain as a ‘spell’. The next day an irate man stormed into his classroom – a convert to Tibetan Buddhism who happened to be the father of one of the students – and demanded to know why my friend had besmirched and misrepresented his chosen religion).

Sorcerer and Vajrayanist Jason Miller has touched on the extent to which many non-Tibetans involved with Vajrayana both resist conceptualizing tantric ritual as magic and are drawn to traditional practices precisely because they see these as particular magical technologies worthy of study. Tibetan tantric Buddhism’s relationship with the label magic and technical vocabularies associated with it is linked directly with the ways in which Tibetan tantric Buddhism has historically been represented by non-Tibetan scholars. These representations have undergone some rather dramatic reversals. The Protestant biases of early European scholars of Buddhism shaped their vision of an ideal, transcendent, pure and original ‘real Buddhism’, which for them, was a Buddhism grounded in the utterances of a historical Buddha as found in the oldest available textual sources in Pali and Sanskrit. This imagined ur-Buddhism was pre-eminently rational, personal, philosophical and anti-ritualistic. The notion that India had declined from an earlier Golden Age served to legitimate European colonial presence there, and the idea that original Buddhism represented a purely rational, anti-ritualistic philosophy was by extension more reflective of colonial imaginings than the actual social and political milieux from which Buddhism had emerged in India and in which it continued to be practiced by native Buddhists around the world contemporary with these scholars. This ‘pure’, ‘original’ or ‘early’ Buddhism as it was variously called thus appeared as the culmination of scholars’ own Protestant values thrown back into primordial time. According to this scheme, contemporary Theravadan Buddhism with its closed cannon was deemed to be the closest living descendant of this mythic ‘Early Buddhism’. Tibetan tantric Buddhism stood by contrast at the furthest point from this feted original. If Theravada Buddhism had best preserved the earliest teachings of the Buddha, the Buddhism of Tibet, with its multiple deities, elaborate rituals, non-celibate religious specialists and supposed feudal theocracy could barely be counted as Buddhism at all. Embodying all of the worst excesses of Catholicism, and betokening the greatest degeneration and dissolution of the original teachings, the Tibetan variety did not even merit inclusion – rather than label it Buddhism, scholars called it ‘Lamaism’ instead.

All the loaded, othering power of the term ‘magic’ was thus cast onto tantric Buddhism. Tantra was magic, and magic was folk superstition, a gross if inevitable overlay obscuring true and pristine Buddhist teachings. L. Austine Waddell, British scholar and colonial official exemplifies this position well. As he informs his readers in the introduction to his 1894 work on ‘Tibetan Buddhism or Lamaism’ “the bulk of the Lamaist cults comprise much deep-rooted devil worship and sorcery…For Lamaism is only thinly and imperfectly varnished over with Buddhist symbolism, beneath which the sinister growth of poly-demonist superstition darkly appears.” On the other hand, as understanding about the nature and evolution of esoteric Buddhism has grown and as scholars have interrogated the colonial and racist agendas that have shaped representations of tantric traditions, describing tantric Buddhism as a set of magical practices or as a magical philosophy has fallen out of favour. Furthermore, following China’s brutal occupation and invasion of Tibet, refugee lamas have been remarkably successful at rebranding Tibetan Buddhism and correcting misrepresentations of tantra as some sort of demon-worshiping superstition – to their credit they have managed to convey the enormous complexity and profundity of the Secret Mantra and have amassed students from all walks of life, many of whom are unaware of the enormous complexity and profundity of the magical traditions and philosophies of ‘the West’ and for whom ‘magic’ is sometimes something of a dirty word.

(Can Buddhism be ‘modern’, ‘scientific’, ‘rational’ and involve magic and spirits at the same time? What might ‘tantric modernity’ look like? I don’t know, but I do know that if Bill Nye practiced tantra, he’d probably not call it magic)

So much for conjuring Buddhas then. Beyond reflecting broadly on what sorts of productive connections could be fostered by thinking of ‘inviting’ spiritual beings in Vajrayana as a form of magical conjuration, it’s worth thinking in a bit more detail about another aspect of the term jendren as well, namely its specific sensory associations.

Neither invitation nor conjuration captures the specifically visual dimensions of jendren, for translated directly, the term literally means ‘to pull the eye’. The centrality of the visual imagination in the practice of tantric ritual has been much commented upon. For the tantric Buddhist, to summon a spiritual being is pretty much synonymous with visualizing it in as much sensory fullness as possible. Stephen Beyer, one of the few writers to provide a sustained discussion on the convergences and divergences between Western ritual magic traditions and Vajrayana, attributes this pre-eminence of the visual imagination to a specific kind of tantric yogic ontology:

“It throws a sharp metaphorical light upon the world of the Tibetan yogin to say that he lives in this totally fluid surrealist universe, that his visualization creates a surrealist imaginary landscape projected upon the very fabric of reality; his private realm of freedom and power is indeed an echo of Breton’s rhetorical question, “What if everything in the Beyond is actually here, now, in the present, with us?” Ferdinand Alquie might well be describing the Tibetans: “They admit, then, more or less explicitly, the postulates of this conception: identity of sensation and image, proper existence °f images, power of actualization inherent in the image.”

This provocative surrealist model, however, gives only a limited analogue for the total collapse of the boundary between the public and private universes. What the surrealists call their “magic” indeed increases the repertoire of awareness, adding the imaginary to the objective at the same ontological level. But where the surrealist image is thrust upon a reality already given in experience, the Tibetan yogin sees the complete and absolute interpenetration of the two unitary fields. His image and his object are not superimposed, but rather are primordially one, and this is what makes possible his magical ability to manipulate the universe.” (87-88)

The theme of pleasing visual offerings and imaginative indulgence, of ‘feasting the inner eye’, surfaces in a related word in Tibetan jenzik, a technical term used to refer to imagined and physical offerings given to protector spirits. A compound word, jenzik (spyan gzigs) can be literally translated as ‘eye-look’ or perhaps more elegantly as ‘(sumptuous) lookables’. The importance of satisfying the visual hunger of the spirits is clear. To return to the previous example of the liturgy for Tsiu Marpo, the text states as follows:

“If you wish to fulfil and restore vows (i.e. perform the kangso expiation rites, say as follows):

KYE! Owner of the vital-force of beings!

The terrifying display of the hosts of the seven groups of spirits!

For you to eat and enjoy:

Red torma cakes of flesh and blood will be heaped like mountains!

Unpolluted nectar will pool like an ocean!

Offering bowls of rakta (i.e. blood/ritual blood substitute) will fill up like lakes!

Offerings pleasing to look at (i.e. jenzik) and riches will spread out like the stars!

The music of drums and flutes will thunder like a dragon!

Accompanied by hosts of melodious songs and tunes,

Vows of the seven sibling oath-bound spirits be amended and fulfilled!

Vows of the wild, blazing Tsen be amended and fulfilled!

Vows of the group of eight spirits, groups united, be amended and fulfilled!

Vows of the oath-bound spirits who protect the holdings of the temple be amended and fulfilled!

Vows of the messengers of the four (magical) activities be amended and fulfilled!”

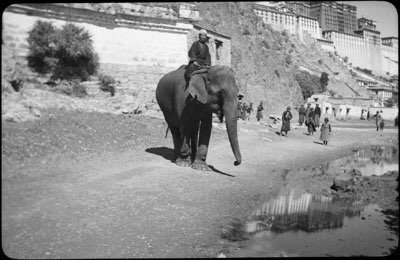

Physical offerings are here amplified through visualization, and a full range of sensory modalities are exercised. The images conjured are vivid, and a clear connection is made between the spirits’ propitiation and the sumptuousness of the ritualist’s imagination. Jenzik typically take the form of the sorts of things that any visitor to a protector-deity shrine or gönkhang might see piled in that space: animal pelts, animal skulls and other parts – especially of carnivores or predators but also yaks and sheep etc – silk hangings, weapons (guns, knives, bows etc), armour and so on. Outside of its specific association with protector spirits, jenzik has the larger meaning of any sumptuous, pleasing, extravagant offering given to a figure of authority, such as a lama, chief, or king. These may often take the form of live animals, especially particularly impressive, expensive or exotic ones. If readers are reminded here of the elephant given to Pope Leo X in the 16th century, they should be. Some Tibetan dictionaries specifically link jenzik to zoo animals, and gloss the term as something that might provide sustained or recurring pleasure for some important person through the act of looking.

(The House of the Lü, Lhasa, pre-1959)

A day or two ago I came across this old picture of the Lükhang ཀླུ་ཁང། ‘The Lü (or Naga, i.e. water spirit) House’ or temple located in a lake behind the Potala Palace, pre-1959 (incidentally, Lükhang was recently the subject of a major exhibition called ‘Tibet’s Secret Temple’ partly organized by Ian Baker at the Wellcome Gallery). While reading more about the temple and its history in a Tibetan book called ‘Guide to the Sacred Sites of the Lhasa Area’ ༼ལྷ་ས་ས་ཁུལ་གྱི་གནས་ཡིག༽ published in 2004 by Chöpel, I discovered that the Dalai Lamas had also once possessed their own jenzik elephant. Chöpel’s account (pp.45-47) offers a brief glimpse into the elephant’s daily routine and provides some interesting details about how a living (and in this case apparently trained) jenzik may continue to give offerings or serve as an offering through its presence or behaviour:

“The House of the Lü Behind the Fortress

The House of Lü can be seen behind the Potala Palace. It was established in the seventeenth century during the time of the Fifth Dalai Lama, during the expansion of the Potala Palace, after earth was dug up and the small lake or pond (on which it is located) formed. There was a small rocky mountain in the middle of the pond and there was also said to be an ‘accomplishment’ or meditation cave and the Sixth Dalai Lama built the Lü House or temple (there) to ensure that rains would fall timeously.

After that, in the time of the Eighth Dalai Lama Jampel Gyatso the Potala’s three-storied roof with four doors in the four directions was built. This is the form which can be seen now. In the lower-most part of the temple Maldro Sijen the resplendent Naga King is featured prominently encircled by the eight great nagas, in the middle story is a representation of the Buddha as the King of the Nagas, and on the upper level in a mural in the Dalai Lama’s small chamber are pictures of Tibetan goddesses performing different scenes, illustrations of tsalung (channel-wind) yogic exercises, and the assemblies of peaceful and wrathful deities (of the intermediary state). On the upper-most level there is a Chinese pagoda style roof of gold and copper.

Both the Eighth Dalai Lama the Victorious Jampel Gyatso and Tenpai Nyima the Panchen Lama made rain fall by accomplishing a lü vase rite at the holy site. From that point on, the religious community of Namgyal Monastery were required to successively perform these. In former times, on the morning of the 15th day of the month of Saka Dawa community members of Lhasa would walk the lingkhor circumambulation circuit and in the afternoon they would gather at the sacred temple and send out a leather-skin boat and sing songs and details from great saints biographies and would go on pilgrimage to the shrine. There they would perform naga spirit feasts beloved by the Buddhist community and naga songs and music and so on. From behind the Lükhang one could see the Potala Palace in its entirety and it was surrounded all around by green trees that had crept up over many years.

On the south facing side of Lükhang was the elephant’s residence, known as the ‘elephant house’. The elephant’s drinking water wasn’t the water from the Lükhang lake – there was a spring on the path going to Draklha Lüpoog, ‘The Rocky Cliff God Naga Cave’ [a sacred cave in the Chagpori mountain range with naga carvings developed by the wife of King Songtsen Gampo] and so each day the elephant was herded there and had to be brought to (the spring) to be given water. When the elephant arrived at the front of the Potala it would turn to face the Palace and illustrate its respect with its lip (trunk?) three times. Then after it had finished drinking water it was taken through the Rocky Cliff Kaling Stupa Gate back to its own dwelling. Currently, the shrine is doing well: repaired images have been newly erected in place of the previously mentioned images and statues and a bow-shaped bridge made of Chinese masonry has also been constructed.”

This has already been a pretty rambling and disjointed post, so I won’t keep you much longer. What can we take away here? Generally speaking, translation focuses our attention in specific ways and this can affect our understanding of ritual practice. The visual vocabularies of Tibetan tantric ritual and offering procedures for spirits tell us something about how the interior spaces of ritual practice are conceived and are thought to operate. One could say that to ‘pull the eye’ of spirits is to make use of the creative imagination to produce a ‘pleasure garden’ of resonant, affectively-charged images through which the mind becomes a sort of miraculous ‘petting zoo’ filled with unfolding displays of visual and other sensory delights that pull in spirit visitors and coax them to stay a while. Given the absolute ubiquity of visualization in tantric Buddhism it is a little surprising that so few in-depth studies of visuality, visualization, imagination and emotion are available. As I touched on in a previous post, sensory attunement and affective/attention training are a key component of tantric Buddhist and ritual magic practice, so I can only hope that more work on all of this is forthcoming. Jake Dalton is currently developing new historical research based on early Tibetan-language tantric ritual manuals from Dunhuang about the emergence of vivid, poetic, affective registers in Buddhist practice and the role of sensory imagination in tantric liturgy, and Sthaneshwar Timalsina came out not too long ago with two very interesting looking books (which I admittedly have yet to read) about tantric imagery and visualization and visual culture from a cognitive perspective, which look like they get at some of the issues I’m gesturing towards here in considerably more technical detail. To close, I encourage readers to check out Phil Hine’s excellent set of posts on tantric visualization at his blog. Here, Phil reminds us what is at stake in tantric visualization, and points to the densely layered cognitive and emotional processes involved in coming to see (and to know) the gods:

“Visualization…requires that the practitioner is familiar to some degree with (a) the image (b) the mythic narratives which relate to the deity, and (c) the theology – both general and particular – in which the deity is embedded. It is relatively easy for outsiders to the traditions to collect information on the particular signifiers relating to a deity; to read the major (and minor) narratives in which a deity appears, and to find a wealth of material relating to the theologies & philosophies with which one can begin to understand a deity within a particular context. However, it is in practice that all these ‘pieces’ are brought together and made meaningful – which can be a long process. Visualisation is more than simply a matter of matter of memorising images or reciting words – it requires actively incorporating insights and realisations which arise out of practice – those sudden flashes of “oh, I get that now” which make all the difference.”

(The 13th Dalai Lama’s elephant, on the path on the south-side of the Potala Palace, 1936, photograph by Evan Yorke Nepean. Nepean was a wireless-communications expert who was part of a 1936 British Political Mission and radio programme to Tibet, supported by the Tibetan government at the time. See more in Nepean’s obituary here)

Pingback: Three Rivers

Pingback: Tibetan Spells for Calling Vultures to a Corpse: On Human-Bird Relations and Practicing Magic | A Perfumed Skull

Pingback: Tibetan Master Meets Theosophical Mahatmas: Gendun Choepel’s Reflections on Blavatsky and Theosophy | A Perfumed Skull

Pingback: Amplify Your Perception: The Ultimate Upgrade - Mindhacker