(A Himalayan vulture coming in for landing)

A day or two ago I was looking through a compilation of simple Tibetan healing rituals when I came across a short entry on a genre of Tibetan magic that I find quite lovely and interesting: vulture summoning spells. I thought I would share these spells here and offer some reflections on why I found them significant.

The so-called ‘collection of assorted rites,’ ‘mantra compilation’ or ‘tantric grimoire’ which I was reading (las tshogs, sngags ‘bum, sngags kyi be’u bum pronounced something like leh-ts’ho(k), nguhk boom, and nguhkee bayew boom, respectively) was published in 2008 by Tibetan scholars connected with the Arura Medical institute and Tibetan Medical Research Association in Tso ngö (Kokonor, Amdo), Xinghai Province, who put out the work as part of a publication series aimed at preserving ancient Tibetan medical texts (see here, for an earlier discussion on this blog about the volume and some of its contents).

(Las sna tshogs pa’i sngags bcos be’u bum, ‘A Mantra Healing Grimoire of Diverse Rites’ prepared by Arura and published by the People’s Press in 2008.)

The particular spells which I’ve translated into English below were excerpted from the tantric grimoire of Ju Mipham, a great 19th century Tibetan Nyingma/Rimé master who spent considerable time and energy collecting together various mantras and magical rites from across the breadth of Tibetans’ traditions and lineages, and publishing these to make them more accessible to the general, literate Tibetan public (Mipham Rinpoche also got a small shout-out in my last post, for those interested. In the short translation below, I include pertinent mantric formulae in roughly phonetic transliteration as they appear in the text. In previous posts I have redacted parts of such tantric formulae when offering such translations by default, but I have decided to leave the mantras in full here because they are not particularly destructive in quality or likely to be actively used or needed by non-specialist readers, and because great Tibetan scholar-adepts like Ju Mipham and Troru Tsenam saw fit to include them in widely available Tibetan texts as well. It is important to understand though that mantras ought to be received directly from the lips of a qualified teacher, from trained experts who have themselves ‘accumulated’ recitations of the mantra and have through their general conduct and ritual mastery empowered the mantra and rendered it efficacious. While it is true that mantras are bden tshig (dents’hik) or ‘words of truth’, which possess a kind of innate power and efficacy by virtue of their being a product of the gnosis of great, spiritually accomplished adepts, ‘mantric speech’ remains most effective when it has been carefully cultivated as part of spiritual training.

(A painting of Ju Mipham (Namgyal Gyatso) Rinpoche, 1846-1912.)

In the spells below, succinct as they are, we see a number of familiar features from such tantric ritual cultivation – visualizing oneself as a Buddha or deity when performing rites, the importance of correspondence between inner and outer ‘auspicious links’ – the aligning of body, speech, and mind with the materials and environment of the rite, and so on. What I like about these examples though, is that even though they present fairly standard ‘working procedures’ from the Indian tantric Buddhist traditions that Tibetans inherited, they demonstrate in a wonderful and rather blatant way how magic adapts to the needs and circumstances of its users. The importance of demonstrating an Indian pedigree for Tibetan renderings of Buddhist scriptures, and even a so-called ‘cultural inferiority complex’ on the part of Tibetans vis-à-vis the noble land of India from which the Dharma (predominantly) came has been noted often enough by scholars. This anxiety to prove the Indian ‘original’ appears clearly for example in the case of so-called ‘grey texts’, scriptures which show signs of having been either partly or wholly composed by Tibetans in languages other than Sanskrit, yet for which original Sanskrit titles were then retroactively engineered. Yet despite such observations, adherence to Indian models at the expense of indigenous needs and knowledge has hardly been slavish or the only orientation for Tibetans.

(Now antique Zoroastrian ‘Towers of Silence’ or Dakhma in the Iranian city of Yazd.)

Archaeological evidence suggests that the practice of what has come to be known in English as ‘sky burial’, and what Tibetans call bya gtor, jhah-tohr, literally ‘scattering or casting to the birds’, where specially prepared human corpses are offered to birds of carrion (specifically vultures) to devour, is an ancient and likely pre-Buddhist practice in culturally Tibetan areas. At the same time, it has come to be intricately tied up with Indo-Tibetan tantric Buddhism, with reflections on impermanence, the centrality of charnel-ground practice in tantric contexts, with Bodhisattva-like self-sacrificing generosity, and the Chöd (gcod) or Severance rite where practitioners visit terrifying, haunted locations and work with the energy of their fear of annihilation by meditatively disengaging from their body, severing their investment in a constructed self, and offering their corpses up to be eaten by hungry, suffering beings (see here for Heather Stoddard’s article exploring how ‘decharnement’ burial rites from Persian Zoroastrians may have diffused into Tibetan cultural centers via Sogdiana at precisely the same time that gcod meditative traditions entered Tibet from the Indian sub-continent to the South to produce a kind of ‘symbiosis in the cultural consciousness of the increasingly Buddhicized population’ of Tibet). Simply put though, Indian tantric Buddhists did not really practice sky burial, and the spells below present a unique mixture of ritual approaches tooled to specifically Tibetan environmental and cultural concerns. While having the means to reliably summon birds of carrion to quickly dispose of a corpse is not a skill or ritual practice many converts to Tibetan tantric Buddhism today are learning, and as much as such procedures might strike some readers as somewhat outre, calling vultures is undeniably an important and everyday practical concern in a context where below-the-ground burial can be difficult to accomplish and fire wood for cremation is limited in many areas.

The mantras too in many of the procedures below can be linked to words in ordinary Tibetan rather than Sanskrit speech (LANG is a Tibetan ox, PHOB is an imperative meaning Cause to descend! Come down! GYANG means from afar, DING means to fly or soar, SHAR SHAR means at once, and so on). Even in this small example then, we see how Tibetans placed inordinate stress on an unbroken continuity with Indian practices, Sanskrit transmissions and the like, even as they quickly developed a vigorous ‘open canon’ where new uniquely Tibetan mantras and ritual procedures continued – and continue – to be revealed through the experimentation and gnosis of native practitioners. Take a look:

Methods to Call Vultures to a Corpse

In addition, if you would call birds [the word here is just bya, which means a generic bird, but the implied sense throughout is vulture, which is called jhagö, bya rgod, ‘wild bird’] to a corpse write the mantra ‘OM DOR LANG SVAHA (SOHA)’ on a flat stone and place this on the heart-center of the corpse and this will free it from evil spirits like shed spirits [gshed are a kind of ‘exterminator’ demon that seize the life-force from the sick and dying].The general mantra for calling birds to a corpse is SARVA DZA YE KA YA – one chants this 108 times, blows it to the four directions followed by forceful blasts on a kangling or tantric human thigh-bone flute. One imagines that the birds assemble like snow falling from the sky by doing which they arrive. There’s also this mantra which one recites 103 times onto small stones or pebbles. One imagines that the stones are vultures and throws and scatters them (through the air) as a result of which the birds assuredly come: OM LING KHUG LING KHUG DZA, profoundly.

Alternatively, when you want to call vultures, meditate that you are a red dakini or tantric goddess riding on a vulture. Cast out the gek or ambient spiritual obstacles, make a sur offering [a burnt offering for hungry deceased spirits] and then chant one round of the chöd or Severance ‘body-donation’ liturgy [this refers to the common Tibetan meditative practice of offering up one’s corpse in the imagination as an offering and food for spirits, Buddhas and other beings]. Then recite this mantra onto as many stones as the number of years the deceased lived, and scatter these on the cadaver: OM DOR LING PHOB! DING DING PHOB! GYANG GYANG PHOB! SHAR SHAR PHOB! THIB THOB PHOB! Chant this 108 times. This rite comes from the ‘Secretly Sealed Esoteric Instructions’ of Padampa Sangye.

One other method is to draw on four flat stones the form of four vultures, inside which you write four mantras, which you then place at each of the four directions or on top of the corpse. Further, if you want the birds to assemble, have someone born in the bird year place them and offer big sang and zur burnt offerings for the corpse and chant the mantra BA RI MA SHAM SHAM and the vultures will come down quickly.”

When I posted a version of this translation on a Folk Necromancy social media group I am a member of, one fellow member commented on the post to ask why anyone would need to call a vulture to a corpse at all. “They’re just kind of waiting for one constantly, ya know. Unless you needed a WHOLE LOT to cover up a murder…”

(Evil vultures in Disney’s ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’)

This question – as well as the link between vultures and the criminal and/or nefarious which it implies – highlights important differences in cultural histories and understandings of both magic and human-vulture relations. One immediately noteworthy point is the general values ascribed to vultures in Tibetan contexts. Vulture bones and feathers are used as important ritual objects, and where vultures have typically appeared as dirty, sinister, opportunistic, and evil-minded in Western representations (just think about which of your friends you’d sooner assign a vulture than a hawk or eagle patronus to, for example), in Tibetan contexts they are the ‘King of Birds’ (bya rgyal, jhah-gyal), and the freest, most undomesticated, dignified of feathery, winged creatures. In Tibetan the vulture is simply ‘the wild bird’ – a perfect embodiment of the untamed, expansive landscape, of natural potency in all its splendour, freedom and ferocity. Since this ‘wild, natural space’ is also the iconic space of the yogic practitioner, the drang srong bya rgyal thang dkar rgod po or ‘upright rishi or sage-like King of Birds, the White Vulture’ is also commonly used as a metaphor to refer to the most accomplished of ascetics. In a teaching song on tantric inner alchemy, the Great female treasure revealer Sera Khandro uses the image to admonish her readers to not speak profligately of the Secret Mantra teachings, to spend time in retreat, to keep esoteric instructions securely and privately in their own hearts-and-minds so as to focus on their personal cultivation above all else:

(A statue of Sera Khandro, 1892-1940, courtesy of Christina Monson)

མདོར་བསྡུས་ཟུར་ཙམ་བརྗོད་པས།། གནས་ཚང་བྲག་ལ་བརྟེན་པའི།།

བྱ་རྒྱལ་ཐང་དཀར་རྒོད་པོ།། རྩལ་གསུམ་༼ལྟ་བསྒོམ་སྤྱོད་པ་མཐར་ཕྱིན༽་ལུས་ལ་རྫོགས་ཆེ།།

དེ་བཞིན་ཐུགས་ལ་ཟུངས་མཛོད།། བྱ་ཕྲན་རྩལ་མེད་རྣམས་ལ།། རླུང་ཕྱོགས་ཙམ་ཡང་མ་སྤེལ།།

Like the great King of Birds, the white vulture whose (retreat-like) home is fixed firmly on the rocky crags,

And who achieves in his own body the great perfection of the consummation of the three skills of View, Meditation and Conduct,

Speak of this only in a brief, indirect way,

And hold this in your heart without even breathing a word of it in the direction of those who lack such skills and are trifling in their actions!

In a similar vein, the great tantric yogi Shabkar uses the white rishi-like vulture in a number of his songs of realization to describe his own spiritual commitment and allude to the non-attachment and letting go into infinite space and impermanence that is so important to Dzogchen or Ati Yoga meditative practice (While the translation of Sera Khandro is my own, the one that follows comes from Matthieu Ricard’s translation in ‘The Life of Shabkar’: The Autobiography of a Tibetan Yogi’. In light of negative cultural associations with vultures for non-Tibetan readers, Ricard substitutes ‘eagle’ throughout). In one song Shabkar sees an actual white vulture flying in the sky above him while he is addressing a group of people who have come to hear him preach, which triggers the following song:

(A tapestry depicting the celebrated Tibetan tantric yogi or ngakpa, Shakbar Tsokdruk Rangdrol, 1781-1851, from Shechen monastery)

The white eagle, the rishi,

Having grown feathers and wings in the

nest,

Flung himself from the cliff and flew out

into the sky.

Now he soars higher and higher into space.

I, the disciple of an authentic guru,

Having heard the teachings and

Contemplated them in my master’s

presence,

Severed all doubts and misconceptions,

and then wandered off into the

wilderness.

Now I persevere in my meditation.”

And at another point, singing to fellow yogic practitioners living in retreat on the slopes of the holy mountain Kailash, he proclaims:

“All of you white snow lions,

Roaming about in the high snows,

Tossing your beautiful turquoise

manes,

Stay here in these same snows.

Having circled the mountain once,The sage, the white eagle,

Glancing back at the Snow Mountain

Continues on toward distant places.

Brother and sister disciplesWho live on the four sides of Kailash,

Stay in this great sacred place

And further your practice.”

Beyond cultural associations and vulture-philia versus vulture-phobia however, something else useful to keep in mind when trying to understand why a whole genre of magic for calling birds to a corpse would even be necessary when it is kind of those birds’ job-description to, well, eat corpses might be this. Corpse-butchers, yogis and lamas necessarily develop relationships over time with local non-human persons at specific sky burial and charnel grounds. It stands to reason that vultures in specific places would get to know specific human practitioners over the years, and although wild, would come to develop certain routines. I’m reminded of an old fisherman I’ve watched on a few occasions at Hout Bay harbour in Cape Town, South Africa who has befriended a number of local, wild seals, including one particularly monstrous one eyed bull seal, which he calls to and who swim up to the side of the pier, which he then feeds fish guts to out of his mouth by leaning over the water, much to the delight/horror of passers-by and tourists.

Human-vulture relationships as these relate to sky burial can be quite specific and intricate. Sometimes the largest and most authoritative of a party of vultures is understood to be their leader and must be invited formally and signalled to come forward and eat specific parts of the prepared corpse first, in a specific manner, after making specific calls etc. Birds behavior during such procedures can be ominous and is also capable of being influenced favourably by magic.

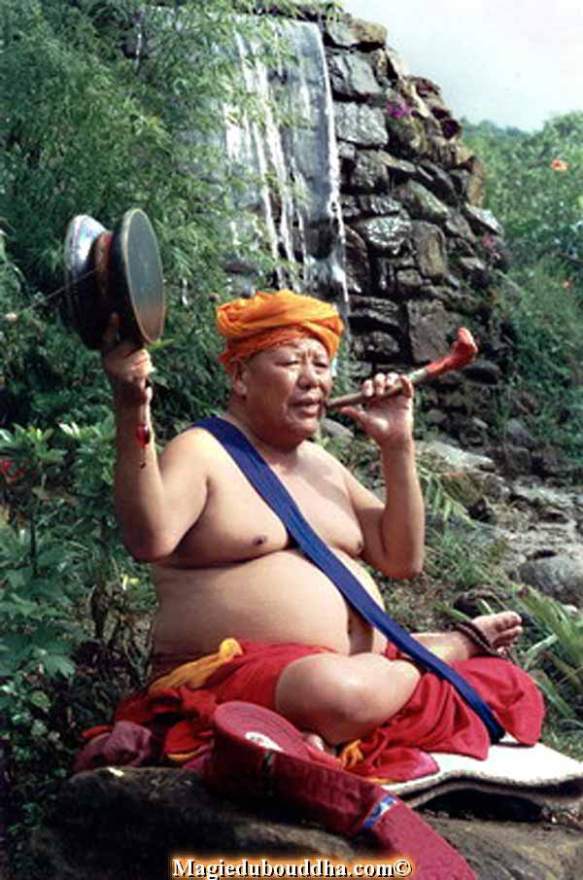

In the following excerpts from his memoir ‘Hundred Thousand Rays of the Sun’, famous Kathmandu-based Tibetan Chöd yogi Lama Wangdu offers an eye-witness account of these kinds of human-bird dynamics.

Tantric Buddhist ritual expertise itself also allows for the possibility that the relationship between vultures and yogis can be more than just poetic. In his own excerpted memoirs, another Tibetan Chöd master in exile, Ngakpa Yeshe Dorje describes how the lama who started his reincarnation lineage in the 17th century was able to practice vulture magic by fully transforming into a vulture himself. As with Shabkar, the connection between vultures, yogic power and flight, and Dzogchen-style practices involving light and space is immediately apparent (Fans of Mircea Eliade’s take on shamanism eat-your-heart out!):

“The lineage began at the time of the fifth Dala’i Lama with a ngak’phang Lama called Drüpthob Tashi. He was a ngak’phang togden who lived as a family man and his practice was mainly concerned with the integrating his realisation with the ordinary particulars of his existence. At that time, the central government was imposing inordinate taxes on his village, and the people were suffering a great deal as a result. The local governor used to extort the taxes by force when the people complained that they could not meet the unreasonable demands that were being made on them. Drüpthob Tashi was touched by the plight of the people and decided to help them in resist the demands. He made himself directly responsible to the governor in the rôle of local head-man, so that he would have to be called upon to make the payment rather than the people. In this rôle he offered the taxes the people could actually afford, and this caused the local governor considerable anger. He responded by sending armed soldiers to force Drüpthob Tashi to pay the entire sum demanded. Over fifty men arrived with guns and swords and surrounded his house, whilst a smaller group broke in and tied his sang-yum and children to pillars. Drüpthob Tashi was on the roof when the assault on his house began, and unable to protect his family. It was his custom to meditated on the roof where he could stare into the sky, and where he could integrate with air-element. Because he was unable to descend and help to his family, he simply waited for them to attack him. They shouted up to him to come down, but he refused to come unless the soldiers released his family. The armed men declined, and scaled the walls in order to apprehend him. Once on the roof, they proceeding to menace him, demanding that he pay the money the village ostensibly still owed – but Drüpthob Tashi’s response dismayed them completely. He threw off his clothes and flew into the sky. The troops were terrified by this spectacle and threw themselves on the ground. Some began making fervent prostrations and beginning his forgiveness. Those below, in the house, untied his sang-yum and family immediately and apologised for the ignominy to which they had been subjected. When the local governor heard about this, he realised the Drüpthob Tashi was a realised being, and felt highly anxious about what he had done. He had no choice, in terms of his cultural background, but to conclude that Drüpthob Tashi must have had very good reasons for defying the demands for taxes. After this event the taxes were reviewed and thereafter, people were treated fairly.

Drüpthob Tashi was quite extraordinary in his abilities. He had the capacity to transform himself into a white vulture in order to appear to different beings and provide them with causes for liberation. He gave teaching in vulture from especially to the vultures who eat human corpses during sky burial, and it was said that the vultures who only eat human corpses after he had blessed them by tapping them three times with his beak. He would then return to human form and re-join his family. His lineage was transmitted to his son, and then from father to son, down through the generations until the birth of Yeshé Dorje Rinpoche. Yeshé Dorje Rinpoche’s father had been the incarnation of Drüpthob Tashi, and Yeshé Dorje Rinpoche was incarnation of the son…”

In his memoirs, Ngakpa Yeshe Dorje also describes what ritualists ought to do when the ‘King’ vulture refuses to eat, namely, they must embody the King vulture and consume a small amount of the corpse’s flesh themselves in order to coach the boss-bird (and subsequently all others in his retinue) to eat:

In response to the above query then about why the need for vulture-summoning rites at all, I suggest that the spells outlined above can be read as part of an overall ritualization and empowerment of idealized human-bird/bird-spirit ‘etiquette’ and of reality in general. They can also be seen as an example of what professional sorcerer Jason Miller has described as the golden rule of effective magic: Come up with a plan of action to realize your goals that doesn’t involve magic, then use magic to ensure it succeeds. Vultures may certainly eat corpses anyway, but magic is always about more than just the anyway. I’d hazard that spells like this are a really good example of this kind of thing, which so many people who do magic as a part-time and counter-cultural hobby can forget.

(Bronislaw Malinowksi doing a great job fitting in with some Trobriand Islanders)

Although he was a professional anthropologist and not a professional sorcerer, Bronislaw Malinowski pointed out something very similar decades ago when discussing magic in the Trobriand Islands. Malinowski noted that the three areas where Trobrianders relied most on magic were sailing, gardening and cultivating romantic and sexual relationships. Significantly, he pointed out that these were all areas in which Trobrianders were considerably technically skilled. But they were also still areas of everyday life that were plagued by many uncontrollable variables and which all depended on the cultivation of sensorial, body-mind-emotional control, of deep levels of attention and confidence (for a fuller discussion on magic, anthropology, ritual and the training of attention, see here and here). More than just a piece of cultural exotica specific to one religious context then, vulture-summoning spells represent not only fertile ground for multi-species ethnography but point too to something crucial about how and why magic is performed, and how it ties in with an auspicious aligning and ritualizing of human life and relationships.

* For those interested, anthropologist Mark S. Mosko published a reappraisal of Malinowski’s classic theorizing of Trobriander theories of magical efficacy and magically efficacious words – that is, the extent to which the correct use of magical words themselves are understood to make a spell efficacious versus the relationships the ritual specialist has cultivated with helping spirits – which dovetails nicely with the above discussion of mantras. Mosko’s article can be read and downloaded for free here.

* Anthropologist Ken Bauer has alerted me to a 2013 documentary film called ‘Vultures of Tibet’ by American wildlife film-maker Russell O. Bush. I have yet to see it myself, but the film delves into contemporary issues of globalization, cultural commodification, voyeurism and social media, changing ecology and Chinese-Tibetan political relations as these have come to bear on the practice of sky burial. Bauer_Review_Vultures-of-Tibet. For readers interested in an informed snap-shot of some of the cultural and political dynamics affecting such burial practices, I highly recommend both reading Ken’s review and checking out the film if possible.

**Another addendum: I was recently looking over a fascinating text which I ended up discussing with the aforementioned Jason Miller (and which Jason ended up mentioning in a blog post of his own, https://www.strategicsorcery.net/whole-magic-part-1-mind-vs-materia/ ). The text in question is a letsok (las tshogs) or a text of ‘assorted [magical] rites’ called ‘the Necklace or Garland of Treasures’, and comes from a cycle of revealed teachings on Tibetan tantric yoga known as ‘The Secret Treasury of the Dakinis dealing with the Channels and Winds’ (rtsa rlung mkha’ ‘gro’i gsang mdzod), which was revealed by the eighteenth century Bonpo/Nyingma treasure revealer Kundrol Drakpa. This letsok is interesting for how it describes how yogis and yoginis who have mastered training in Tummo or ‘inner heat’ yoga and various forms of yogic breathwork can then go on to use Tummo yogic techniques in the performance of everyday sorcery (the text describes several different operations, everything from using Tummo yoga to blow up a building, attract friends, make/halt rain and other weather patterns, develop clairvoyance, summon the consciousnesses of recently deceased individuals from the intermediary state between rebirth, to breaking up lovers and staving off thirst or hunger). As Jason highlights in his post above, this text demonstrates that working practical magic using more interior, or de-materialized ‘mind-and-energy’ methods is far from some modern, New Agey psychologization of magical procedures, it is a traditional approach of indigenous Indo-Tibetan tantric tradition. At the same time, further proving Jason’s point about the value of balancing mental processes with ritual ‘materia’ – the familiar, outer ‘eye of newt’ aspects of spellcraft – the text offers many examples of Tibetan tantric yogic ‘spells’ where the use of ritual materials is seamlessly integated with more ‘mind/energy/breath’ based methods.

Pingback: Ritual Conservation in Ancient Rome – Napkin Scrawlings

Pingback: A Tibetan Ghost Story: How Three Chod-pas Tamed a Yakshini | A Perfumed Skull

Pingback: Mirroring the Master: Making Magic in a Nineteenth Century Tibetan Book of Spells | A Perfumed Skull

Pingback: IL VOLO INELUDIBILE DEL TACCONDOR - Spada Magnetica