I was wafting around a second-hand clothing store when I was in Cape Town, South Africa in December last year when I came across a curious little volume hidden behind some piles of clothing and gaudy costume jewelry. The book’s single word title ‘Inyanga’ caught my eye. Inyanga is a technical term in isiZulu and isiXhosa for a particular kind of traditional healer or curer (more on the technical specifications or lack thereof of this designation later). Written by white South African writer and journalist Lilian Simon, Inyanga was published in 1993, one year before the abolition of Apartheid, and constitutes a kind-of memoir for prominent black South African traditional healer Sarah Mashele. From roughly the 1950s until the present (I have not been able to determine yet if she is still alive) Sarah Mashele worked full-time as a healer in and around Pretoria and Johannesburg – and in the formally blacks-only segregated urban neighbourhood of Soweto in particular – providing services to patients across the race, class and cultural spectrum. I just finished reading the book, and so I thought I would offer a review of it as well as some reflections on its contents and Simon and Mashele’s collaboration for interested readers.

Even with Simon’s ‘Madam’-y demeanour and pearl-clutching about the supposed psychic ‘darkness’ in which Sarah and her native peers are steeped (more on this later), the bulk of Inyanga’s pages, in which Sarah speaks to us through lightly edited interview transcripts, offers rich ethnographic and biographic material on everything from religious and medical pluralism, cross-cultural psychiatry, spirit work, ritual healing, divination, witchcraft, and gender in mid-20th century South Africa. Readers versed in familiar-spirit and witchcraft related traditions from early modern Britain, will notice in Christian-raised Sarah’s accounts of meetings with ancestral spirit-helpers, local nature spirits and spirits of the dead striking similarities with the sorts of visionary encounters with familiar spirits experienced by European visionary healers known as cunning men and women which historian Emma Wilby, for example, has so wonderfully collated in her work (Incidentally, Wilby herself attests to the viability of cross-cultural comparison in this regard in devoting one section of her book to comparing British cunning wo/men’s accounts of their initiations and working relations with spirits with the parallel narratives of more contemporary Siberian and North American shamans).

Readers of this blog and those who have listened to some of the interviews I’ve done will know that I am very interested in the ways that specialist and often very local and community/context-specific esoteric knowledge becomes globalized, commodified, repositioned, and re-imagined. I had never heard of Sarah Mashele before I discovered Simon’s book, but further research after reading it confirmed that ‘Dr Mashele’ was already quite successful and famous locally – and somewhat unusually, globally – years before her meeting with Simon. Beyond considering some of the interesting points that emerge from Sarah’s narratives then, I’d like to reflect a little in this post as well on other writers and journalists’ framings of Sarah and her practice from the 1960s to 1990s. In addition, I’d like to consider what happens when particular indigenous ritual specialists become iconic for audiences based well outside their home communities, what fame and wide circulation can mean for indigenous healers.

(A portrait of Sarah Mashele with her signature rings from the early 1970’s, as featured in Joy Kuhn’s book of photo essays about twelve black South African personalities, ‘Twelve Shades of Black’. Sarah’s glamorous and ‘modern’ style persistently fascinated her white interlocutors)

Talking to Skeletons in the Garden: Hearing the Voices of the Dead in pre-1994 South Africa

Sarah Mashele’s account of her life as a healer begins with her childhood in the late 1940s in and around Eersterus(t) outside of Pretoria (portions of Eersterust would later be formally christened coloured-majority areas in 1958, following the institution of the Group Areas Act of 1950 that demanded that race groups live in segregated communities. Many black families apparently bought plots there, however). The spiritual experiences and ‘sickness’ that inaugurated Sarah’s life as a healer began when Sarah was nine years old. Sarah notes that she was a girl who had no interest in or time for the pursuits and frivolities of her peers. She was instead a serious child, older than her years, something both she and those around her noticed and remarked upon. She was strongly given to prayer and solitude as a child and was raised Christian in an African Zionist context (Zionist aka African Independent Churches are widespread in South Africa and rather than having any connection to Zionism originally derive from the Christian Catholic Apostolic Church, which with its emphasis on faith healing was an early influence on the development of Pentecostalism). She also fixated on purification:

“I was washing more than the other children – I always wanted to go to the river to swim or bath, to clean myself. It was funny; after having a bath I had to sit right in the sun. I really liked to be in the sun.”

Sarah’s sickness, which ‘white doctors’ (Western bio-medical doctors) were unable to properly diagnose or cure entailed a suite of symptoms common to ‘shamanic’ spirit sickness and the vocational ‘madness’ which indicates that a person must become a healer, and which is commonly referred to by the isiXhosa/isiZulu word ukuthwasa in the South African context (ukuthwasa literally means ‘to wax’, and like inyanga – which can also mean ‘month’ – points to a cultural logic linking visionary capacity and madness to the moon). Sarah tells us that during the day she heard voices and noises in her head and felt as if somebody was with her invisibly. This persistent voice and presence was strongest while she was praying, and when Sarah “was outside under a tree…right in the shadow of the tree.” This voice belonged to an older tall man who would appear to Sarah every night in her dreams. The man wore a long white dress or robe which covered most of his body, and which prevented Sarah from clearly seeing the man’s face or hands. In her dreams Sarah would ‘throw the bones’ and animals and people would emerge from them (‘to throw the bones’ refers to a divinatory procedure used by many ritual specialists in South Africa where patients cast an assortment of special consecrated bones, shells, stones, and pieces of horn and wood onto a mat and these are interpreted by the diviner).

Sarah did not initially understand these dreams, and they troubled her. Along with these dreams, she experienced a general malaise and sense of dissociation. Her experiences came to a head when the voice of the man in white told her one day that the minister of her church would soon die as a result of witchcraft-related poisoning, and that she should publicly prophesy his death (in a separate interview in a book called Twelve Shades of Black which I will discuss below, Sarah identifies the man whose death she foretold as a friend of the minister instead). Filled with confidence and certainty, Sarah does as the voice commands, much to the alarm of her parents, the minister and her fellow congregants. The minister dies and nine year old Sarah goes on to correctly predict the sudden death of an elderly female neighbour, who subsequently appears to Sarah as a restless spirit. Despite regular beatings from her mother, Sarah’s ‘witch things’ show no sign of abating. Take a look (for non-South African readers a sjambok is a kind of heavy whip, made of either leather of plastic):

There are many points of interest in all this. Scholars of Tibetan Buddhism will find parallels between Sarah’s childhood narratives and stories about སྤྲུལ་སྐུ། ཡང་སྲིད། tulku/yangsi reincarnate lama children, who often also exhibit adult-like propensities and a disinterest in childish activities, an impulse for cleanliness and purification, and a propensity for religiosity. Sarah’s nameless initial spirit-helper, who is later confirmed by another inyanga to be one of Sarah’s male healer ancestors (white clothing and appearance is frequently associated with ancestral spirits in South Africa) demonstrates a similar ruthlessness and directness to the familiar-spirits described in Wilby’s cunning wo/men accounts. After Sarah’s sickness fails to improve, her parents bring her to her paternal grandmother’s farm, hoping a change of scenery will help her convalesce. Sarah’s granny is also an inyanga albeit one whose scope of powers and expertise (in this case midwifery and fertility magic) seems somewhat more limited compared to her granddaughter’s (it is at this point that we learn more about Sarah’s ancestors too – Sarah comes from both maternal and paternal lineages of izinyanga, and she credits the origins of her hereditary powers to her maternal great grandfather, who was a Christian prophet and faith healer). While staying with her granny, Sarah is again visited by the man in white, who gives her specific and firm instructions. Sarah’s description makes clear the forcefulness of her spirit-helper and his communications, and the non-negotiable quality of their transactions:

We see here clearly the tensions and reconciliations between Christian and pre-/non-Christian affiliations and loyalties that exist for many ritual healers around the world. In an equally common theme, Sarah also struggles to balance her commitments to the spirits with her own everyday interests, and her responsibilities as a daughter. ‘Don’t listen to her, listen to me’ her ancestor tells her, reminding us of the way that spirits around the world often jealously covet their human mouth-pieces, sometimes even to the point of obstructing and causing harm to human kin in the process, something I briefly discussed in an earlier post.

Another striking feature of Sarah’s anecdotes is the often public nature of her anomalous experiences. Intense as her literally shat-in-her-pants encounter in the garden with the skeleton-shade of the old lady neighbour may be, the ante is significantly upped when another neighbour, Mrs Bopape reveals that she heard Sarah talking to the skeleton in the garden and heard it talk back. Sarah’s prophesies are also engineered by her ancestor to be as public as possible – he tells her that it was necessary for her to make the announcements she did so that the community could see without a doubt that she possessed genuine abilities to help them (for a related discussion on public ‘miracles’ in the Tibetan Buddhist context, see my post here). Indeed, after her initial dire pronouncements come to pass, community members begin to approach nine year old Sarah for more general advice, and slowly come to trust her.

Lessons from Snakes: Visionary knowledge and Competing and Complimentary Categories of Ritual Expertise

Another especially dramatic public display of Sarah’s power and spirit-contacts occurs a little later, at the climax of Sarah’s long journey to resolve her spirit-sickness. Despite her impressive displays of power (which include performing a make-shift emergency birth procedure with a razor for a woman in labour), Sarah’s condition continues to deteriorate. Eventually, the man in the white robe tells Sarah she must travel with her parents all the way to Rhodesia (current-day Zimbabwe) by donkey and foot, to find a specific inyanga by the name of Mr Tiko, who will be able to help her. Her parents reluctantly agree and led by the advice from the man in white garnered in visions and dreams, Sarah and her parents eventually arrive at the home of Mr Tiko, a wealthy-seeming local healer who has been expecting them as a result of his own visions, and who runs a school for trainee-izinyanga attached to his house. It is here that Sarah experiences perhaps her greatest and most important spirit-encounter. The trigger for this event is Sarah’s realization that Mr Tiko and his assistants plan to initiate her as an isangoma, that is to say, an ancestral spirit-medium, diviner and healer who frequently relies on communal drumming to enter trance. The man in white informs Sarah that she is not meant to become an isangoma and terrified, Sarah flees from Mr Tiko and his drum-beating entourage. What happens next is in turns remarkable and typical:

The idea that select people can journey to another realm of being located either under the sea or beneath rivers is pervasive in South Africa. This place is almost always populated by some variety of shape-shifting serpent entities, who in certain instances, can impart precious healing knowledge and substances to curers (scholars of Buddhism will note the similarity here with naga/nagini, and will be reminded of the master Nagarjuna, who was likewise instructed by powerful serpents underwater). As we see in Sarah’s account, these snakes are not always unanimously helpful or accommodating. Indeed, giant snakes are as much associated with the power and protection of the ancestors as they are with more insidious spiritual forces. Family and friends are usually warned when a prospective healer is taken under not to mourn by crying tears, lest their loved one never returns (in a different interview Sarah admits that her mother did indeed break down, but it seems that the support Sarah received from the less hostile snakes was sufficient to prevent her permanent disappearance). The offering of a white goat to the snakes, on the advice of Mr Tiko, is sufficient to seal the deal. Again, we are presented with an example of the miraculous, of a situation that challenges everyday rules of time-and-space, and yet it appears to be one corroborated by witnesses. It’s tempting to treat Sarah’s underwater ordeal as a purely visionary experience, one that did not involve her physical dislocation at all. But Sarah speculates that she was absent for six months, and she claims a crowd of people were present to witness the arrival and departure of her water snake teacher.

(An alleged photograph of the infamous inkanyamba of Howick Falls, largely believed to be a hoax. For more on the photograph/story, see cryptozoologist Richard Freeman’s blog entry)

Sarah’s description of her snake teachers, and especially the details of her rocket-like return to dry land combine elements associated with the inkanyamba – the male inkanyamba is said to be a wind or tornado-snake who tunnels through the air at great cost to humans and the environment in search of his mate, a female serpent who lives deep under water. Many possible snakes can be found in South African cosmology, but common to all of them is a certain ambiguity. Anthropologist Hammond-Tooke famously laid out how in Cape Nguni cosmology the river and riverside represent a morally ambiguous space. Situated between the safety and human order of the homestead and the outright wildness and otherness of the witch and spirit-infested forest, the river is both a domain of vital importance for the maintaining of life and prosperity and one fraught with dangers. It is thus no surprise that the zone of the river and its spirits has become intimately connected with the decidedly morally ambiguous allure of capitalist accumulation and Western global modernity. In an excellent article on the ritual procedure of ukuthwala, a special practice in which one gains possession of a highly dangerous and blood-thirsty mamlambo, a shape-shifting serpentine succubus-like water-spirit in order to generate wealth and good fortune and the Sotho medicine-man Khotso Sethuntsa who himself become fabulously wealthy by initiating customers into the practice, Felicity Wood offers a thorough analysis of traditional ideas about snake spirits in South Africa and newer stories relating to mamlambo which embodies both the mystique and Faustian devastation of capitalist modernity.

(As a child growing up in Durban, Kwa-Zulu Natal, I remember being warned not to swim alone in the sea for some months because a red car that would suddenly emerge like a submarine was abducting bathers, taking them prisoner in a world of serpents. At another point, commuters were warned about a similarly red mini-bus taxi, which despite initially looking and behaving like an ordinary vehicle, would transform into a giant snake and kidnap passengers, taking them to a place underground where they would be turned into zombies and be forced to live as slaves to the snake people and the tokoloshe. A tokoloshe or tikiloshe is a common, much feared demon/nature spirit that appears when seen in various human and bestial forms, but most commonly as a vaguely humanoid and hairy dwarf. The tokoloshe is said to like to live near rivers. Despite his tiny stature he has an enormous penis which he slings over his shoulder when not in use. He is said to be either captured or made by witches and sent to cause discord and misfortune in the homes of enemies. He produces poltergeist-like phenomena, possesses people, and has sex like a sort of incubus with his victims, causing them all manner of woes. He is said to sometimes be kind to children, who see him more readily than adults. He does not like electrical wires and can be blocked and chased away with sea water and other special medicines. ‘Inyanga’ includes an extended narrative from Sarah about a whole family oppressed by the tokoloshe, whose power even Sarah worried might be too strong for her to safely deal with)

In addition to differing typologies of spirit beings, Sarah’s account also offers us a glimpse of the ways ritual specialists must navigate the social recognition and validation of their powers in terms of overlapping but nonetheless differently weighted and differently valued typologies of spirit-worker or ritual expert. Both Sarah and the man in white powerfully resist induction as an isangoma and it is worth asking why and why it might be that Sarah’s initiatic ordeal takes place in concert with this resistance. Sarah is at pains to distinguish herself as an inyanga from a host of other potentially comparable, but nonetheless different categories of local ritual specialist. Part of her refusal of both the ethno-centric label ‘witch-doctor’ and isangoma is that she understands both these labels to imply practitioners of murderous magic, to stand for magical mercenaries for hire willing to kill their clients’ enemies for cash. Sarah’s much repeated line in the sand is that she will never do such ‘evil work’ – for her, izinyanga only ‘help people’ and never harm them. They busy themselves solely with combating evil sorcery and never with performing it:

Despite these qualifications, in at least one of her consultation stories, we see Sarah at least apparently willing to use muthi (plant/animal/mineral based magical-medicine) to ‘shut up’ a cuckolded husband and make him meek and submissive so that the man sleeping with his wife can continue to do so without interference, which is an arguably more aggressive and un-Christian way of ‘helping people’ than one might expect. And in a 1965 newspaper story about Sarah’s Soweto practice, ‘Young Woman Prospers as a Witch Doctor: Johannesburg Area Gives Her, at 28, a Busy Life’, journalist Joseph Lelyveld notes:

“When a visitor pointed to a mask on top of one of her filing cabinets and asked what it was [Sarah’s] husband genially explained that it could be endowed with a life and movement of its own to do evil deeds. If you didn’t know ehat a car was and saw one parked at the curb he said, you’d be astonished to hear it could travel at 90 miles an hour. It was the same with the mask, he explained.

The visitor must have looked skeptical. “Do you want me to send it to you tonight in bed?” the witch doctor asked, laughing. The visitor demurred.”

In Sarah’s account of her childhood as well, we see signs of the fear that fellow Sowetans have that Sarah may in fact be a witch or practitioner of murderous magic – the common theme of the ‘shifty’ and dubious quality of healers’ potential power to both curse and cure is plain, and in the special feature above we see Sarah using this ambiguity to her own, and to comedic advantage. While Sarah’s critique of the term ‘witch-doctor’ above is that it is too vague and racially-loaded, the word nonetheless appears throughout her narrative and seems to often stand as an index for non-Christian activities, affiliations and values from which Sarah at times seems to want to distance herself. There is another dimension to Sarah’s resistance to izangoma however. It’s clear that Mr Tiko and his associates thought that Sarah had the capacity to be an isangoma, but by refusing to commit to the requirements of training as one, Sarah arguably secures for herself a measure of autonomy and flexibility – as Sarah spins it, in addition to involving the consumption of alcohol, being an isangoma ties one to the inexorable pounding of the drums and to particular, potentially confining social configurations and communities (the drummers who drum, the spirits who come and so on). Throughout her story Sarah reiterates that her helping spirits intend for her to be a healer for all people, and her disappearance into the water and tutelage by the snakes demonstrates that Sarah’s status and power as a healer holds with or without strict (human) mediation and the support of specific communities (it is interesting too that Sarah leaves South Africa to seek assistance in dealing with her spirit sickness). While it’s clear that Sarah learns a great deal from her year or more long mentorship under Mr Tiko, she presents the snakes as the ones who teach her everything she knows, and frames Mr Tiko’s interventions more as being about recognizing and stabilizing her knowledge and talents rather than transmitting or endowing them.

In Twelve Shades of Black Joy Kuhn picks up on this theme somewhat sarcastically:

“Sarah Mashele presence is strong and commanding. When she talks of the snake’s concern for the common man her listeners forget cynicism: “He told me when he left that I must love the people – help the people – be patient with the people because I am going to meet all sorts of people in trouble, and after that Mr Tiko washed me with medicine and told me he knew what the snake had said and the sickness went away from me and I began to cure people.”

Later, attempting to be cynical, one feels that Sarah had a lucky shortcut: most witchdoctors are initiated into the intricacies of their art only after five years of instruction, an examination and an oath-taking ceremony. They are taught the medicinal properties of herbs, much about man himself, and about wild animals. They must have a sound knowledge of tribal history, learn to pray in rigid form, calling on deceased ancestors by name, before proceeding on to the “magic” itself, and the throwing of the bones.”

Here Kuhn projects an idealized picture of the education of a tribal medicine-man, and uses it to cast a side-eye on Sarah’s own training. Kuhn is unaware that Sarah did in fact undergo an examination (as is typical she was made to locate a hidden item with clairvoyance during a party thrown in her honour after her training with Mr Tiko comes to an end), and more pertinently, Kuhn fails to appreciate that neither traditional healing nor ‘African tradition’ itself is a monolith.

At school in the 90s in Durban, Kwa-Zulu Natal I was taught normative definitions of izangoma and izinyanga in isiZulu class: an inyanga was more properly a herbalist, who unlike the isangoma could train in their craft with or without spirit sickness vocation, and without experiencing possession or having any visionary capacity. In addition the distinction was proposed that izinyanga were like pharmacists and izangoma were the diagnosticians or GPs. Sarah’s life belies such neat distinctions. Sarah is a Christian, admits to having had visions of Christ, is taught by pre-Christian nature spirits, and despite not being an isangoma exhibits marked visionary capacity and a talent for mediumship. At one point, Sarah goes to the home of an old, rich, morose white widow, and in the course of throwing the bones experiences an overwhelming buzzing in her head and loses consciousness. She wakes up sometime later disorientated and sprawled on the rug, to be greeted by her wide-eyed client who says that she had slipped into trance and the voice of the widow’s husband had spoken through her, offering shockingly accurate and intimate information. This client tells Sarah she would make a wonderful spiritualist medium, and Sarah goes with her to a few Spiritualist Church séances where she hears the voices of the deceased again and mediumizes impressively for a spiritualist audience.

Snakes, Popes, and Weed Plants: Rethinking Religious Syncretism

This melange and overlap of roles, influences and commitments is hardly unusual or surprising. Yet Sarah’s syncretism seems to both fascinate and mystify journalists, who can’t quite wrap their head around Sarah’s heterogeneous cultural world and healing practice. In a 1998 article for the London Independent, ‘Healers Reluctant to Share Secrets With Medical Giants’, Mary Braid visits Sarah’s clinic and tells us:

“The Pope beams down on Dr Sarah Mashele’s waiting room, sharing wall space with a Native American prophecy about human greed, a warning that smoking causes cancer and a painting of a sangoma chatting to a water serpent.

The bizarre fusion of Catholicism and traditional African beliefs, modern technology and magic, continues in Dr Mashele’s consulting room in a Johannesburg tower block otherwise filled with dentists, GPs and chiropodists…”

A snide Liz Sly for the Chicago Tribune, writing her own version of the white journalist ‘safari journalism’ involving traditional healers I discuss in this post, also mentions the portrait of Pope John Paul II which she says dominates the room along with ‘a huge marijuana plant’.

Rather than focus on the spectacle of syncretism for its own sake and get pulled into tired, red herring discussions about indigenous tradition and ‘authenticity’ versus modernity and cultural hybridity, a more productive anthropological question here would be to ask what cultural logics, personal preferences, and historical, economic and political conditions shape specific practitioners’ religious choices and commitments. To explore how individual practitioners and community navigate their ties and responsibilities to different human and non-human persons and communities, and to what effect. In his 2014 book Food, Sex, and Strangers: Understanding Religion as Everyday Life, scholar of Paganism, animism and a host of other things Graham Harvey addresses the peculiar way in which the charge of ‘eclecticism’ or religious syncretism reifies religious ‘tradition’ in a way that entirely misrepresents the nature of religious activity:

“The notion of hybridity is sometimes played out in allegations that one group of religionists or another treat “other cultures” as a “spiritual supermarket”. Setting aside the spurious insistence that religion and economics should be categorically separated, the supermarket metaphor fails precisely by being untrue to anyone’s shopping habits. It is a fact that some of the Pagans who participate in sweat-lodges also celebrate northwest European seasonal ceremonies, create ritual working spaces following nineteenth-century protocols, play didgeridoos, venerate or invoke Greek, Roman, “Celtic” or other deities, and otherwise fuse performative materials from diverse sources. However, just like a visit to the supermarket, there are underlying factors that determine and make sense of the choices people make…

In addition to the objections that the “spiritual supermarket” metaphor fails to recognize pre-existing conditions as determinants of shopping habits, it seems to treat religions as different from other activities undertaken in modernity. What is it about religion that leads some observers to think eclecticism (if that occurs) is improper among religions? Once again, the notion of boundaries between religions and between religion and the rest of culture is evident. … Just as studies of lived religion are likely to demonstrate that “syncretism” labels something so ordinary as it render it uninteresting (except to those who imagine religions differently), so they ought to propel us away from the inadequate polemic about supermarkets. This is not to disavow critiques of the ways in which people adopt and adapt from others any more than it is to approve of theft from supermarkets. It is however, to indicate that not all learning is (negatively inflected) appropriation.”

Sarah herself addresses the hybridity of her cultural and linguistic environment:

“the different tribes have different ways. Maybe the Zulu inyanga will not give you the same medicine as the one from Vendaland, and the sangomas from different places will not always do the same things. My father was a Tswana and my mother is a Venda so I am already not just from one tribe, and I grew up in Eersterus where the tribes are all mixed up so the ways are changing. Now I am married to a Swazi and we speak Zulu at home.”

It is thus telling that despite Sarah’s own acknowledgement of her own cultural and historical particularism, Simon is still content to imagine that Sarah speaks for black South African tradition writ large, that Sarah successfully captures something of a native psyche beyond time and space, or any other particulars.

Exchanging Tribal Masks for Cars and Bank Books: Sarah Mashele in the International Press

(A shot of the exterior of Sarah’s ‘surgery’ in the early 1970s, from ‘Twelve Shades of Black’)

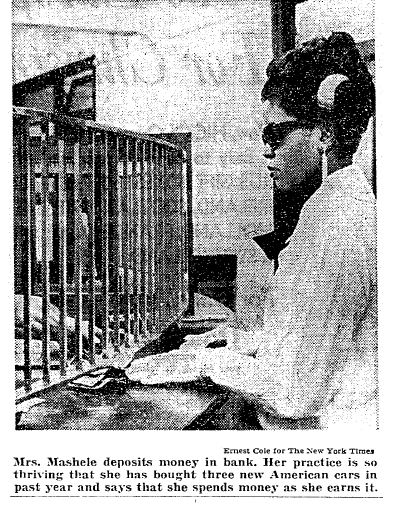

The rhetoric of ‘timeless indigenous tradition’ versus modernity and both the alienation and progress it brings dominates in cases where ‘traditional practitioners’ go global. When Sarah appears in international media the focus of journalists’ articles is almost always on 1) Sarah’s modern appearance and tastes (her fashion sense, her jewellery, her multiple expensive imported cars and 2) the amount of money that Sarah charges for and makes from her services. Journalists can’t seem to get over Sarah’s alternative modernity, that witch-doctoring is not only a brisk but also a lucrative trade, that Sarah likes to wear rings on each finger and fur coats (a fact mentioned on the back cover of Simon’s book and foregrounded in the photo-journalism of Twelve Shades of Black), that Sarah has her ‘clinic’ in a high-rise alongside actual doctors and lawyers’ offices, that Sarah is rich from providing magical services for clients.

(Examples of media representations of Sarah Mashele – a 1966 news piece also from the Chicago Tribune – I wonder if Liz Sly knows she was scooped more than three decades prior? – which uses a stock image of a ‘witch-doctor in tribal garb’ to size up Mashele; we see Mashele depositing money in the bank, and references to her prices and her cars abound)

As South African anthropologists John and Jean Comaroff have shown, dress – which extends into broader cultural, historical ideas about hygiene and personhood – has served as a primary vector in colonial civilizing projects in both South Africa and elsewhere. This focus on clothing, tastes and class betrays journalists’ inability to understand what Peter Geschiere has dubbed the ‘modernity of witchcraft’.

Every Zulu Child Knows You Must Bury UFO Debris: Global Shamans, the Politics of Indigenous Authenticity and Speaking in the Name of Tradition

Regardless of their somewhat misguided representations, the international attention Sarah garnered from such journalists’ treatments appears to have served her well enough. Sarah’s association with foreignness and her extensive non-black client base seems to have added to her charisma (see here for some earlier ruminations of mine on the role of ‘foreigness’ in South African healing and magic). Yet, when specific forms of local knowledge go global they can be radically transformed, both for better and worse.

(Credo ‘I believe’ Mutwa)

The case of South African ‘Zulu shaman’ or isangoma Credo Vasamazulu Mutwa is instructive. Mutwa, born in 1921 in KwaZulu Natal, recognized his calling to train as a sangoma following an extended period of illness in the wake of his brutal assault and rape by a gang of mine workers at the age of sixteen, during which his body was set on fire. In later life, after an Afrikaner employer in Johannesburg observed his knack for inventing exotic and culturally authentic-sounding narratives to describe crafts and curios he was helping to produce and to sell, Mutwa was encouraged to write a book about African culture for a popular, white audience. The result, Indaba My Children, which was supported by the Apartheid nationalist government’s Department of Bantu Affairs, presented a heady melange of myth, folklore, history, poetry and amateur ethnography that captured the imagination of many a white reader. Africanist scholars, however, while recognizing the book’s literary merit, overwhelmingly called into question the authenticity of its content. Mutwa, despite advocating for the native wisdom of Africans, nonetheless supported separate development as a natural and desirable state of affairs, which he supplemented in the book with his own peculiar origin myth that attributed much of Africans’ wisdom to the influence of ancient, light-skinned foreigners who visited the continent thousands of years ago. In the 1970s ‘Mutwa Village’ was developed under the auspices of the SA National Parks Board. Populated with Mutwa’s striking visionary sculptures, it was designed to embody ‘African tradition,’ boldly and with pride, for the consumption of tourists. In 1976 student supporters of Biko’s black consciousness movement razed the village to the ground for embodying not black pride, but separate development, tribalism and a sham, grossly romanticised and essentialised African past. Mutwa, as self-proclaimed protector of African heritage and a vociferous advocate for apartheid and enemy of the ANC, was unsurprisingly, seen by those fighting against the regime as a set-back to the Struggle – indeed, not only Mutwa’s various enterprises, but also Mutwa himself, was attacked and set alight a second time.

(Yet another kind of magical reptile: Leading conspiracy theorist David Icke – whose fan-base includes everyone from alt-righters, to New Age soccer moms, to Christian Conservatives – along with the wisest man he knows, Credo Mutwa)

In the post-Apartheid context, however, Mutwa has experienced something of a renaissance. A younger generation of black South Africans who know little of the details of his past, and the current national government, have in some instances come to uphold him as a kind of national prophet, despite his previous political allegiances. In addition, scholar of religion David Chidester notes that while Mutwa is unanimously dismissed as a fraud or embarrassment by more informed South Africans, he is currently lauded and supported abroad by New Agers who accept his ‘indigenous authenticity’ with few or no reservations. For the last decade or so, Mutwa has formed a significant partnership with David Icke, probably the world’s best known and best-selling conspiracy theorist. Icke, who claims that the world is controlled by an elite of transdimensional, blood-drinking, shape-shifting reptilian aliens who steer global economic and political structures for the enslavement of our species, has found in Mutwa a powerful, authenticating voice. Mutwa, who has spoken extensively in recent years about his own varied encounters with extraterrestrials – which he claims to have been kidnapped, tortured and turned homosexual by, to have had sex with and eaten, amongst other things – brings the substantiating weight of timeless tradition to the subject of world-wide alien conspiracy.

How is it then, that a man who scholars in the field of African history and cultural life have labelled a charlatan, that at one time was a firm proponent of Apartheid and opponent of the ANC, that, having suffered numerous run-ins with extraterrestrials, who has claimed that the proper disposal through burial of the rubbish left behind after UFO crash-landings is part of ubiquitously known and timeless ‘African tradition’, could have been consulted by investigators from Scotland Yard as an expert for help in cracking a suspected ‘ritual killing’ in 2005, could have been invited to help design and bless as prestigious a monument as Mandela’s Freedom Park, or could be characterised by neo-shaman Bradford Keeney, his friend and patron, as “one of the most revered medicine men in the world”, “the great spiritual leader of Africa”, on whose head, incongruously, the South African and foreign governments are supposed to have put a bounty?

As I mentioned above, popular notions of shamans paint them as repositories of tribal wisdom, the obvious place to seek out time-honoured tradition. Mutwa makes clear, however, that these figures frequently function as prime innovators, existing at once in the centre and the margins of social life. Mary Schmidt has described shamans as ‘epistemological mediators,’ who, having recognised the arbitrary quality of cultural distinctions and ‘givens’ during their dramatic initiation experiences, can creatively re-write and re-order local cosmologies and re-appraise boundaries and borders for healing and change. Despite his apparent absurdity, Mutwa is arguably doing the religious work and fulfilling the roles typical of ‘authentic’ritual specialists. While the extent to which Mutwa is doing this usefully is open to debate, it remains that a number of respected white and black izangoma and spiritual practitioners have gained legitimacy through him. Equally, we cannot ignore or belittle the claims of numerous indigenous ritual specialists who likewise have come forward and discussed their close encounters with UFOs and aliens, experiences which they have readily (re-)interpreted in light of indigenous cosmologies and prevailing political and economic circumstances (Indeed, anthropologist Eirik Saethre who appears to have inadvertently become the primary voice on ‘indigenous ufology’ in anthropology, presents a rich discussion of Walpiri narratives about UFOs and extraterrestrial contact, showing how these “both reflect the local social environment of race relations and affirm Aboriginal identity”. Peruvian ayahuasquero shamans and visionary artists Amaringo and Luna, too, have provided multi-dimensional (pun intended) commentary on shamans’ relationships with apparently ‘extra-terrestrial’ beings, while Jacques Vallee was one of the first researchers of the paranormal to point out the now oft-noted family of resemblances between accounts of shaman-spirit interaction, fairy kidnapping, and contemporary alien abduction).

We could paint Mutwa as a genuine native shaman who has been misappropriated by New Age enthusiasts and conspiracy buffs. Then again, we could also think of him as a prime example of a syncretic neo-shaman himself, marketing his cultural wisdom to outsiders through the internet, and developing bizarre and innovative ties with everyone from white Indian medicine men from North America to visiting Tibetan lamas, to foreigners and researchers from outer space (See the transcript of Rick Martin’s (1999) extraordinary telephonic interview with Mutwa for more details regarding these encounters). Certainly, we cannot dismiss Mutwa entirely as a genuine shaman just because what he has to say strikes us as lurid. In mediating between human and non-human persons for healing and social change both in the more immediate context of his South African surrounds and abroad, he is only doing the work any shaman might. Such a pragmatic view collapses categories of ‘authentic’ or ‘fake’, just as, as Chidester points out, Mutwa himself blurs the lines between neo- and native shamanisms. Through Mutwa’s collaborations with Icke, things like the extensive series of taped interviews Icke has conducted with Mutwa (who Icke calls the wisest man he’s ever known) where Mutwa describes how African tradition and his own experiences as an isangoma confirm the existence of diverse species of extra-terrestrial, Mutwa has been able to disseminate South African indigenous knowledge worldwide. The idiosyncratic and personal visionary quality of Mutwa’s knowledge however, complicates overly simplistic conceptions of communal traditional wisdom.

Who owns the knowledge of the Gods? Tibetan ‘shamans’ in exile

(Anthropologist turned shaman Michael Harner’s seminal text on the principles and practices of his ‘Core Shamanism’ system. Harner experienced a dramatic initiation into shamanism after consuming the hallucinogenic brew ayahuasca while undertaking research with the Jivaro in the Amazon in the sixties. Emerging from his ordeal, with the encouragement of a shaman-informant, Harner began to learn more about shamanic practice. Leaving South America, he studied forms of healing and divinatory practice in various parts of North America. Convinced of the value and efficacy of shamanic procedures for Westerners, Harner endeavoured to re-package what he had learned for a predominantly Euro-American, urban audience. ‘Core Shamanism’ is what emerged – a repertoire of easily learned techniques, culled from ethnographic sources on shamanisms around the globe, designed to induce the alteration of consciousness for the sake of self-transformation and healing. In a democratization of shamanic initiation, one-day seminar and weekend workshop participants are lead through guided ‘soul journeys’ where, lying on the floor and listening to tape-recorded rhythmic drumming, they travel through openings into other worlds and meet and receive power animals and songs and practice the removal of spiritual impurities and obstructions from patients’ bodies)

The Foundation for Shamanic Studies founded by anthropologist turned neo-shaman and ‘Core Shamanism’ founder Michael Harner, and this Foundation’s longstanding sponsorship of the ‘last lha pas,’so-called Tibetan ‘shamans’ or spirit-mediums, offers another example of what can happen when indigenous ritual specialists and their knowledge go global. With Tibetan culture under threat following the People’s Republic of China’s military occupation of Tibet in 1949 and the subsequent displacement of thousands of Tibetans throughout South Asia, Harner’s organization selected the handful of still practicing lha-pa-shamans in two small refugee settlements in Northern Nepal to be the pilot case for his ‘Living Treasures Project’. As living treasures the lha pas receive life-time annual stipends, which have a significant an economic and social impact on the settlement community. Dubois presents this sort of sponsorship in a mostly positive light, and notes that such outsider support can help not only keep alive flagging shamanic ‘traditions’ but revitalize community support and publicity for them, as locals have the opportunity to see how their cultural practices are valued from an outside perspective. This kind of outside interest and support can have unforeseen and negative consequences however. For example, Maria Sabina, the once obscure Mazatec curandera became a household name in psychedelic circles with the discovery of (and much popular press around) an ongoing ‘magic mushroom cult’ in Oaxaca, Mexico, by amateur mycologist Gerald Wasson. Following the massive influx of tourists and spiritual seekers into her area of Mexico looking to use psilocybin mushrooms, Sabina lamented that increasing contact with foreign mushroom users of the psychonaut variety spoiled the power and reduced the elevation the mushrooms had once provided her, and made her a less effective healer (See this short video where Sabina explains how the mushrooms are meant to be used to heal, and not to grant visions of the divine).

(Now deceased Tibetan lha pa ‘shaman’ Pawo Wangchuk experiencing possession by mountain deities and helper spirits as part of a healing ceremony in Pokhara, Nepal. Wangchuk was one of the lha pa sponsored by FSS as a ‘living treasure)

As common-sensical as this discourse of preserving and continuing traditions may appear at first sight (considering the context of radical cultural upheaval in which Tibetans have found themselves post-occupation), there is arguably a paradox here too: while for researchers and neo-shaman outsiders, the ‘knowledge’ to be preserved is plainly Tibetan and ‘cultural’, for the lha pas themselves their ‘knowledge’, power and practices are not strictly their own, or perhaps even theirs to possess, but instead belongs to the particular gods and helping-spirits who may happen to possess them at each séance. What is ‘held’ is a hereditary capacity, a genealogical intimacy with the spirits that comprises a special and mutually constitutive set of relationships. While lha pas express anxiety about the continuation of their lineage in exile, and are concerned about proper training of future generations, they repeatedly point to the capricious and ‘karmic’ dimensions of succession, where the gods will come or they will not, and while the gods might be enticed to return and continue their obligations to their human supplicants, there are no guarantees.

Knowledge preservation efforts such as Harner’s organization’s arguably position shamans as the primary sites – the repositories and custodians – of ‘traditional wisdom’. Despite the centrality of lamas and other more or less institutionalized religious authorities and ritual specialists in identifying, enabling, ratifying and managing mediumistic lineages and abilities, it is yet unclear to me whether Harner’s organization has incorporated lamas and other institutional actors into their vision of cultural preservation and stewardship when it comes to these ‘last lha pa’ living treasures. The politics of cultural preservation as revealed in existing publications surrounding the exile mediums produces a kind of ‘museum effect’, whereby the real meat of ‘culture’ to preserve is the ritual expertise and personal histories of shamans, but taken as a kind of snap-shot, removable from the flow of everyday lived contingencies.

This is arguably of a piece with Harner’s ‘Core Shamanism’ in general, which positions itself as Shamanism genericized. Harner aims to present the basic working ‘technology’ of shamanisms to his students, divested of their socio-political and cultural-historical particulars. Indeed, Harner has suggested that what he sees as shamanism’s paramount feature, namely “the healing aspect – requiring the journey into spirit” is ‘pre-political’, with politics being “an aspect of cultural baggage that is added onto the essence”). This individualistic, almost solipsistic de-contextualization and de-culturalization of shamanisms has prompted New Age shaman-cum-therapist Bradford Keeney to slam the technocratic heartlessness of Harnerist ‘weekend’ shamanism and its ilk. For Keeney such approaches lack love, commitment and community. At the same time Keeney also presents a sanitized portrayal of shamanism – while shamanism remains deeply political and community-based, its politics is one of cosmopolitanism and universal humanism predicated on a global community of practitioners and healers, who through their innate compassion and selflessness transcend national, ethnic, class, gender and even linguistic boundaries. This presents a very different picture of native shamanisms than is outlined for example by anthropologist Whitehead in his discussions on ‘dark shamans’, witchcraft, ritual murder and magical combat in indigenous Amazonian societies.

Harner’s line of reasoning inevitably promotes the over-determination of the label shamanism – shamanism is dissociated from specific, and context-specific social roles and activities, and instead is sited in the shared neurological apparatus of our species. The shaman and shamanic experience are made a-historical and archetypal. The shaman thus becomes an index for the perennial wisdom of humanity, or even stands for an entire neurological ‘epoch’ or constellation (as in-the-vogue neuro-theological/cognitive archaeological accounts by the likes of Winkelman with his comments on shamanism and its links to what he dubs ‘paleomentation’ suggest).What is at stake then is the very idea of knowledge itself: shamanisms, so localized, multiple, ad-hoc, de-centralized and informal in their scope, contrast with the neat packaging of Core shamanism.

The contrast between the portrayal of Living Treasure exile lha pa-shamans by Harner’s organization and that of half Sherpa, half Tibetan ‘insider’ filmmaker Tsering Rhitar’s (1997) is striking. In his documentary Rhitar, familiar with the refugee community where one of the most prominent and most studied lha pa (now deceased) lived, presents a view of the lha pa-shaman that is decidedly less rosy and flattering than that produced by other researchers. We learn that the lha pa was widely reviled as a man, bullying his medium manqué son to the point of attempted suicide and beating his wife so badly she had to be rescued by the local Women’s Association. We hear from community members and patients who avow that while they cannot stand the man, they visit him, because when the god comes, it is effective. Interviewing former patients, family, neighbours, friends and mediums, Rhitar provides a window into the ongoing negotiations surrounding a form of contingent and fraught social practice in exile. Here, the question is not about the extinction of ‘culture’, but the ongoing intimacy and reliability of the gods and men in exile. The reciprocal and contingent nature of relations with the gods – who are highly temperamental, ever ready to take offence, quick to flight, and who require constant appeasement – is made clear here, in ways downplayed by Harner’s representatives’ narratives. Angela Sumegi echoes these thoughts in her 2008 book on shamanism, Tibetan Buddhism, and dreaming:

“The strength of this link with the gods and the essential mutual support between the people and the spirit powers of the landscape of the landscape – the way in which they “elaborate each other” – is brought out in a Bön supplication to Targo, the deity associated with the sacred snow range of the same name in Northern Tibet: “We fulfil the wishes of the lions, tigers, leopards, iron [-colored] wolves, black bears, boars, mi-dred, soaring winged creatures, and wild yaks, and your entire manifested entourage. If there is no one to offer to the gods how can the magical power of the gods come forth? If humans do not have vigilant deities, who will be the supporter of humans?”. Such examples highlight two important characteristics of a shamanic worldview: one, that relationship signifies communication, which takes place between persons; the other, that certain realities are constituted, not given.” (17)

How might we fit these realities into the agenda of cultural preservation as elaborated by Harner’s organization? Interviewing one Tibetan lha pa in 2011 I was struck by how dissatisfied he was by the politics of preservation as he and his family had experienced it in interacting with foreign researchers. While he valued and carefully guarded the visual records made of his father in trance by one anthropologist, he generally expressed disinterest or distaste in previous efforts at documentation of his family’s ‘knowledge’. His relatives had once had their own book he told me – I inferred that instead of an academic style volume offering up interpretative commentary on deity-possession rituals, this book was concerned with recording the generationally evolving relationships between mediums and the gods for posterity. In the juxtaposition of these two different kinds of‘books’ we are offered a final hint about the possible tensions between neo-shamanic and social science research efforts that seek to capture, preserve, understand and process forms of ‘knowledge’ (in Harner’s case for potential cannibalization/re-branding and incorporation in Core shamanic repertoires) and native practitioners’ modes of praxis when it comes to spirit possession and spirit interactions which center on what Charlene Makley has called a ‘politics of presence’ and relationality that could even be said to constitute a special kind of anti-epistemology. Rösing explains the conundrum of attempting to research this sort of shamanic ‘knowledge’ in her appraisal of ‘West Tibetan’ shamans in Ladakh:

“To heal, Sonam [Rosing’s lha pa informant] goes into trance. Only in trance is his knowledge accessible to him (given the fact that he holds that it is not his knowledge but that of the deity who occupies his body when he is in trance). When he is out of trance, this knowledge is subject to amnesia. Knowledge and authentic trance belong together for Sonam. Therefore, Sonam can only teach in trance. I realized that I could not understand the shaman when he was in trance while I was in the state of normal consciousness. But the co-shaman in trance could understand him. So I thought that I must also go into trance so that I can understand him and he can teach me. That is, I have to learn to go into shamanic trance which, in the final analysis, means that I have to become a shaman myself. Finally, after I have become a shaman and can enter into trance and understand him, then I am also subject to amnesia (or, if not, Sonam can correctly claim that my trance is not authentic). Thus I cannot transmit what I have learned. Moreover, it is not so easy to become a shaman. I must first pass through a series of, let us say, “psychopathological” (as we tend to call them) experiences. In other words: to become a researcher of shamans I must first go “crazy.”After I have gone crazy, I can begin to learn and understand. But then I cannot transmit to the outside world what I have learned and understood. The shamanic amnesia has extinguished the role of the researcher. One can only do research on shamans by ceasing to do research. This is the methodological paradox of the shamanic amnesia.”

Fear and Loathing in Soweto: Inter-racial tensions and the making of memoir

If Simon’s book offers a springboard for thinking through the pitfalls and contradictions associated with the global dissemination and reframing of indigenous knowledge, it also offers a context in which to explore more local concerns. Simon published her text in 1993, not long before the birth of democracy in South Africa. It’s clear, however, that a lot of time passed between Simon and Mashele’s interviews and the final publication of the book. Although Simon does not spell it out, internal details (Simon’s reference to the fact that the Soweto riots were underway during the period of her interviews with Mashele, the fact that The World was banned by the Apartheid government in 1977 etc.) indicate that Simon must have met Mashele before 1977. Simon makes no concessions to international readers – the book is littered with South Africanisms, none of which are explained. It does not appear that Simon intended her book to have international circulation or appeal. In the book’s prologue and epilogue, the parts of the text where Simon’s attitudes and concerns feature most strongly, Simon confesses that it was fear and emotional ambivalence about occultism and black South Africans’ cultural practices in general that delayed the completion of the book. Simon foregrounds her reservations right from the outset. In the opening lines of Inyanga, she admits,

“I have been afraid to write about Sarah Mashele and I don’t really know why. Is it because in her there is something I don’t want to accept, something that frightens even as it draws?”

In the book’s epilogue, Simon describes her final in-person meeting with Sarah, during which Simon and her husband visit Sarah’s consulting rooms in Soweto for the first time. Non-South African readers should know that for a white South African to visit an officially black, segregated ‘township’ (a South African term that historically indicated poorer, less-resourced urban areas reserved for non-whites under Apartheid South Africa’s racist policies of ‘separate development’), even without the extreme civil unrest and violent state reprisals taking place at the time, required formal permission from the white supremacist, nationalist government. Passes granted were subject to limitations and curfews (this is part of the reason that Sarah repeatedly describes visiting white clients at their own homes – black South Africans also required passes to visit, work and reside in designated white areas but because white South Africans relied on the ongoing exploitation of non-white labour to maintain their privileged existence and because white South Africans barely numbered ten percent of the total population, the flow of traffic from black neighbourhoods to white ones was far greater, more frequent and normalized than the flow from white to black ones, a situation that still larger holds in post-Apartheid South Africa today). Sarah shows the couple around her ‘surgery’ – she points out magical-medicinal paraphernalia and Lilian makes observations about the room’s set up and décor in a way that, after having read a number of white writer’s accounts can be described as formulaic. As Simon and her husband are leaving the township, escorted by Sarah’s sons, Lilian and her entourage pass a group of children playing soccer. One of them kicks the ball at Sarah’s sons’ car:

“The driver caught it and threw it back. ‘It could have been a stone,’ I thought. ‘If one of them picks up a stone…’”

Simon trails off. But her fixation on disaster and danger, her foregrounding of her own anxieties about black violence and unpredictability segue tellingly into her ‘Heart of Darkness’ concluding thoughts for the book:

“Sarah is my friend and I know that she is continually fighting evil, yet why do I associate her with darkness? Is it the darkness of ignorance or fear? When I lie awake at night it seems to have a shape like an atomic mushroom, growing larger, taking over.

But in the morning it scatters, translucent, wisping away like mist in sunshine. I dial Sarah’s number and a crisp voice says, ‘Dr Mashele’s rooms, I’m sorry, the doctor is busy with a client. Can she ‘phone you back?’

A little while later Sarah’s voice comes across, warm and soft, throbbing into laughter. ‘I’m in a comic,’ she says. ‘They told me today, the people who are fighting TB. They want me to help them so they put me in a comic…I’m going on TV.’

Her laughter stays with me after she puts down the receiver. Gradually it fades and then I remember Sarah sitting in silence, eyes glazing as she stares down at the bones. Will I ever be able to reconcile the darkness with the light?’

This contrast between light and dark persists throughout Simon’s reflections, is the lynch-pin around which she works her narrative. At the start of her epilogue she tells us that,

“Now that I have finished writing about Sarah I can’t stop thinking about her. Sometimes I feel as though she is taking over my mind.

I remember the dogs standing up, hackles rising and a growl dying in their throats as I opened the door to her when we first met. Why didn’t they bark? She stood on the threshold, her head slightly tilted while her eyes followed me, piercing, dissecting. When she made me throw the bones her eyes turned inwards and drew me in with her. She took me out of a brightly lit, modern room into an occult-dark world.”

The rich ethnographic data of the rest of the book, Sarah’s own experiences, are recast through Simon’s soul-searching and ruminations on the reconciliation of ‘darkness’ and ‘light’ – categories pretty unsubtly linked with native black South Africans and their ‘tradition’ and the ‘rational, skeptical modernity’ and ‘civilization’ of whites respectively. Despite their relative brevity, in book-ending Sarah’s story, Simon’s projections and personal quandaries dominate, turning Inyanga into a tale of white anxiety, a story about what Sarah Mashele’s life and work means for one white South African woman, rather than much else.

Sarah Holds the Reins: White Fears and Darkness in the Heart of Africa

Joy Kuhn offers a similar narrative in her shorter account in Twelve Shades of Black. Kuhn’s account of Sarah is initially complimentary, Kuhn warms to Sarah’s ‘operatic’ quality and vibrant story-telling. This changes however, when Kuhn sits down to throw the bones:

Kuhn’s companion ‘David’ is non-plussed – Sarah’s reading for him is also filled with doom and gloom, but she characterizes his life and family inaccurately, and he seems to brushes her off as a manipulative cold-reader, who (wrongly) proposed he had ‘sexual problems’ not because of any clairvoyant ability but because his clothing and jewelry read as ‘camp’. Joy however, is “still upset” and wants “to leave Soweto fast”. As the two are leaving we are treated to a remarkably parallel exit-scene to Simon’s:

Again the focus on the quick-to-turn attentions of black children, money, and the hint of exploitation, again talk of the darkness of superstition somehow endemic to the ‘African soul’. At first Sarah’s photographed hands point to whimsical opulence, an almost endearing if disarming mishmash of cultural markers, influences, expectations, and aspirations. As we continue to read, Sarah’s heavily jewelled hand is framed as something else though, is transformed into the iron grip of tradition, of occult forces manipulated, of fears and intimacies exploited. In the end, what are meant to be records of black South Africans’ indigenous beliefs or knowledge are shown to be just as much records of what white South Africans think they know about black people. Sarah might ‘hold the reins’ when it comes to her psychological impact in the minds of her white interviewers, but in the final analysis she does not hold the reins of her own story-telling. Less curator and more exhibit, we are left to wonder just how much this is Sarah Mashele’s story after all.

Pingback: Indigenous ‘Nature Spirits’, Bio-regional Animisms and the Legal Personhood of Other-than-human Persons | A Perfumed Skull