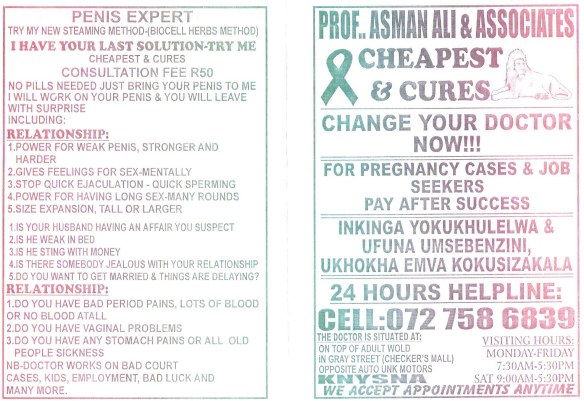

Recently, for laughs, a friend of mine shared this picture on Facebook:

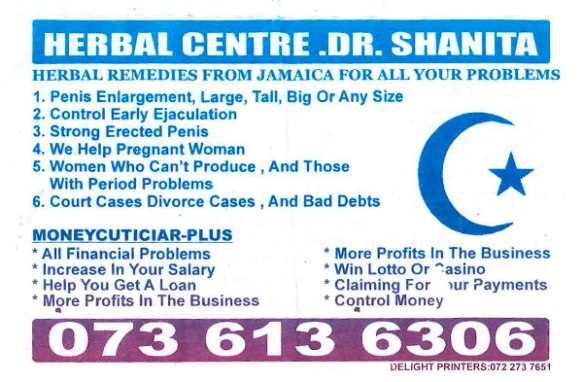

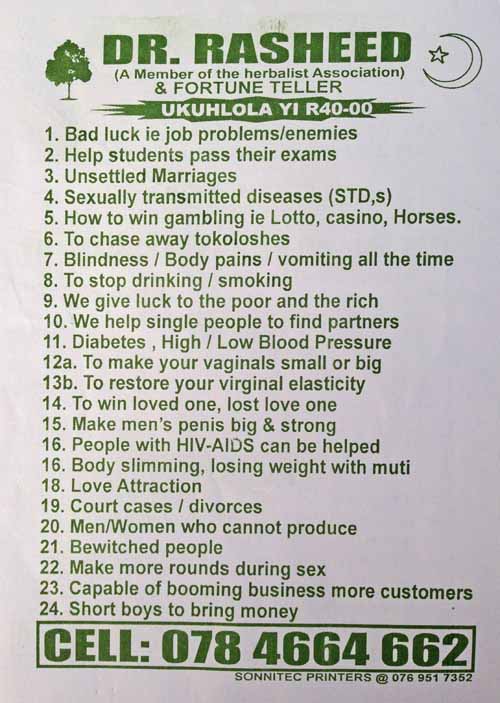

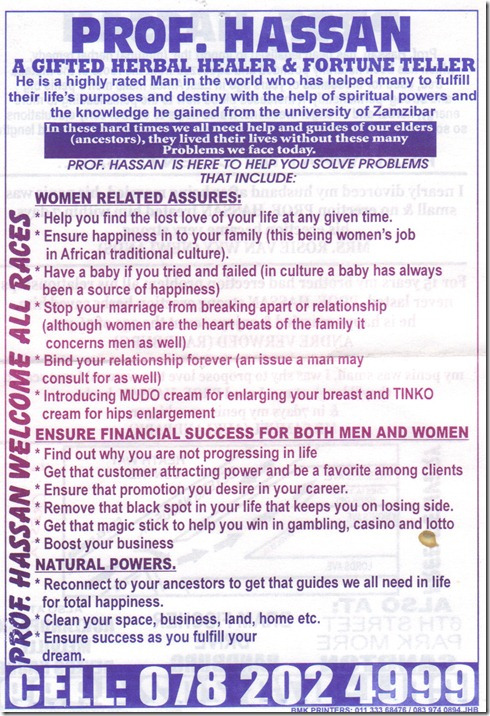

It is a somewhat unique example of a certain type of advertisement that one commonly sees plastered on various public surfaces, handed out as flyers, or posted in classifieds sections all over South Africa. These notices, which advertise the services of various kinds of spiritual doctors, healers and ritual specialists – have become their own genre, and their curious English phrasings, frequent references to exotic materials and methods, and claims to provide such services as penile enlargement, vaginal tightening or the magical return of straying lovers are a regular source of amusement for non-customers and skeptics.

In the thriving magical-medicine marketplace of contemporary South Africa, traditional doctors and healers must equally meet clients’ expectations and stand out from the considerable competition. While South Africa offers a broad array of local ritual specialists – ancestral spirit mediums, diviners, herbalists, and African Zionist preachers, prophets and faith healers – these sorts of adverts by and large come from foreign national healers, whose presence or at least self-promotion appear to have boomed in South Africa within the last ten to twenty years. Foreignness is an important part of these healers’ activities, and not only because of new South African residency, immigration and refugee policies, or the spates of xenophobic violence that have gripped the country since 2008. For the magic and services of these ex-pat medicine-men (and sometimes, women)- who come from all over the continent but especially, it would seem from East Africa – are not merely incidentally foreign by virtue of the passport status of their purveyors, but are intrinsically foreign, by their purveyors’ own admission.

In flyer after flyer, healers’ non-local names and titles appear alongside the more general exoticism of their magical ingredients and tools. Powerful herbs and magico-medical substances (what are known in South African vernacular as muthi, the isiZulu word for various sorts of plant, mineral and animal medicines and ritual substances) are described as coming from all over Africa and the world. Healers claim to have received knowledge and ingredients from everywhere, and the cosmpolitanism of their magic verges on the superlative. In an earlier post discussing primitivism and the ideas of the ‘savage’ as they play out in magic, I noted how “sometimes it can seem like everyone’s always someone else’s Magic Negro and that the most Powerful Magic lurks Forever Faraway at the Periphery, is Always Over And Out There.” Ritual specialists the world over are well-known for their creative bricolage, and it’s rare to find magical systems that don’t evince significant hybridity and syncreticism. We can see from these flyers a great mixture of sources and strategies for appealing to authority. References to foreign healing products and foreign sources of spiritual knowledge and authority rest alongside appeals to more local realities. Local references include regular mention of the tokoloshe, a very active diminutive, hairy animalistic incubus and witches’ familiar with an enormous penis who is chief fodder for South African tabloids and concerns about magical attacks. Like their local counterparts, foreign doctors offer exorcistic procedures for getting rid of the tokoloshe, as well as methods for employing him and other spirits like him (the so-called ‘short boys’) to bring wealth (special spirit rats or amagundane, as well as spirit-snakes and sticks are sometimes advertised by these healers for this purpose as well).

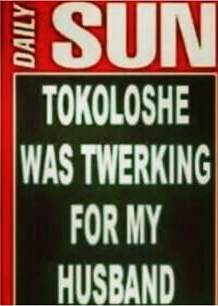

(The tokoloshe features regularly in South Africa’s most sensational tabloid, the Daily Sun)

The opening image’s invocation of the these days pretty much floating signifier of the Illuminati, of secret societies possessing unimaginable power that is global in scope is on one level only natural and sensible for the flyer’s purposes. And yet it is also ludicrous: in popular consciousness the Illuminati is Satanic, overwhelming evil and selfish, and in publicly claiming affiliation with the most secret of elites the good doctor arguably demonstrates he really can be no member at all.Still, by drawing on the now global cachet of Illuminati elite conspiracy theory, the flyer captures in a particularly striking way the idea I’m describing here of ever expanding horizons of foreign and cosmopolitan magical power. The idea that foreignness points to greater efficacy, to greater magic than the humdrum or well-worn methods of ‘home’ is itself hardly an exotic one. One only has to look at the branding and ingredients of any trending tooth cleaning or anti-aging product to see how much ever new and exotic materia medica are relied upon to sell products and ideas. (Another interesting case of new ingredients sprucing up old technologies took place in the 90s in South Africa, when local companies apparently began selling the psychoactive research chemical 2-cb to indigenous sangoma, or Nguni spirit mediums and diviners as an aid for inducing trance-states to communicate with the ancestors. Sangoma/izangoma, while technically an isiZulu word, is used widely in SA as a general term for traditional healers)

The role of foreignness in healing and health has implications beyond the hawking of products and services, however. In his reflections on cross-cultural healing in East Africa, Ole Bjorn Rekdal argues that “a focus on the dynamics and ideology of cross-cultural healing may be crucial for an understanding of processes generated by the encounter between biomedicine and African traditional medical systems.” Traditional structural-functionalist/symbolic-interpretivist ethnographies of cultural healing traditions often risk giving the impression that cultural healing only works or is valued for its ability to embody and engage with particular groups’ collective values, or shared cosmological truths. Here, cultural and ritual healing is therapeutic because it derives from and acts through and upon the terms of a distinct cultural ‘world’, common to healer and patient. However, this ‘cultural world/world-view’ approach, while analytically elegant, is less equipped to deal with cross-cultural therapeutic exchanges, and ignores the fact that the average medical consumer’s health-seeking behaviour tends to be thoroughly pluralistic. Identifying the same ‘search for healing in the culturally distant’ that I note above, Rekdal suggests that “the attribution of power to the culturally distant implies an openness to the unfamiliar, the alien, and the unknown”, an openness to the other which complicates the notion that the ‘native’ must exist within the confines of some closed world of cultural meaning (I discuss this idea a little more in this post on David Graeber’s reflection on magic and the ontological turn in anthropology).

Foreign healers are a highly conspicuous part of today’s pluralistic South African medical-magical landscape. To my knowledge, however, there has been very little ethnographic research conducted on the ways that these foreign healers are interacting with indigenous ritual specialists, their client bases, and other medical practitioners. On the one hand, there seems to now exist a whole genre of ‘cultural safari’ journalism by titillated (white) columnists who describe once-off visits to these healers, but who clearly, by their own direct and indirect admission, do not rely on traditional healers for many of their primary health care needs, like some two-thirds of the South African populace do, at least by some estimates.See here for one example of this kind of safari journalism, where a white female journalist visits several of these doctors apparently to explore cures for ‘women’s problems’, and this highly annoying piece from 2013 by Mail & Guardian editor-in-chief Chris Roper. Roper begins by mentioning his sudden new motivation to pay these ubiquitous flyers more attention, and refers to his new interest in wanting to “re-evaluate how I deal with cultures and classes that aren’t entirely mine”. He explains how a healer’s website he discovered off a flyer caught him off guard and made traditional healers seem ‘less alien’ for him, but ultimately he just ends up reading some flyers and making further snarky comments. “I used to think [these flyers] were a reflection of how dumb people were. Now I realise it’s a picture of how desperate they are.” – he closes by announcing how sad he is to realize the kind of problems poor South Africans have, how desperate and exploitable they are, all without ever bothering to actually talk to either healers or patients (another woman, an artist critical of such healers’ exploitation of patients, has also apparently stockpiled flyers and processed them into ‘problem bowl’ art pieces as social commentary. There is also this website called ‘eish sangoma’ (Yikes! traditional healer) which provides a scanned collection of such flyers as a source of amusement, and from where I got many of the copies of flyers for this post).

(An example of a satirical advertisement riffing off of foreign healers’ flyers from South African fast food Portuguese-style chicken franchise Nandos).

While sangomas have been supplying health care services to South Africans for centuries, it was only in 2007 that the South African government formally recognized them under the ‘Traditional Health Practitioners Act’ as ‘traditional health practitioners’ alongside herbalists, traditional birth-attendants, surgeons and other ritual specialists. This act included in its provisions demands that traditional healers become registered and accredited via new institutional bodies, a process which remains incomplete and contested. Such efforts raise questions about the nature of indigenous knowledge systems. Standardization and institutional regulation depend on the idea of systemic knowledge, yet as scholars such as Murray Last have classically shown, research to document what traditional healers ‘know’ faces particular obstacles that derive from the nature of medical cultures themselves, where not-knowing and non-systems may be as relevant as systemic approaches to health and well-being. In 2008, I studied the role that predominantly white neo-pagans had played alongside one association of sangomas, the Traditional Healer’s Organization, in contesting the language used in an earlier proposed redraft of the Mpumalanga Anti-Witchcraft Bill, designed to curb witchcraft accustations and witchcraft-related violence in that province. While neo-pagans’ ideas about what it meant to self-identify as a witch were strikingly different from those of sangoma witch-hunters, both groups came together and took issue with the way that the Bill criminalized ANYONE who professed to have access to magical substances and powers, and who offered to provide magical services and anti-black magic protections for clients. The Bill included an addendum which required that traditional healers be registered, and provide a list of some twenty-odd plants and substances which they principally used in their personal practice, complete with vernacular and scientific names. Traditional diagnosis and categorization practices for muthi – where different species of plant may function as equivalent healing categories and possess the same or different name depending on context, where the circumstances of a plant’s location, discovery, and harvesting may have as much to do with its efficacy as its active species-specific chemical constituents, and where suggestions from spirits may motivate medicine selection as much as inherited pharmacological knowledge – thus came up against state attempts to manage and regulate indigenous knowledge.

(On a side note, a few months ago my adviser informed me that someone was directed to the Savage Minds anthropology blog I have written for via the Google search ‘how to fight the black witch magic which shrinks the penis’. I shudder to think what will happen now, but hopefully everyone will find the answers they are looking for!)

The category of ‘traditional healer’ has emerged in both popular consciousness and policy in contemporary post-apartheid South Africa as a necessary generalization. Research and journalism, however, has tended to do a poor job of distinguishing and making sense of the internal divisions of practitioner and practice within this sweeping umbrella term. Aside from the more general question of the extent to which oral traditions of ancestral spirit healing can be standardized, much of the existing literature on traditional healers and policy/patient interactions appears to focus on local, healers with established ties to particular communities, especially in rural and peri-urban areas. Far less research exists which focuses specifically on foreign, urban, and migrant healers, who may set up shop in a city block, but may not be tied by bonds of kinship, nationalism, or history to any stable client base. The urban magic0-medical or occult marketplace naturally poses significant challenges for study, but also important opportunities. As my friend Stephen Pentz who is currently developing research around some of these very questions has pointed out to me, as easy as it may be to laugh or shake one’s head at such foreign doctors’ ‘special’ sexual health services, these practitioners (regardless of whether their treatments work, or ultimately help or harm) undoubtedly cater to sizable, especial urban and migrant demographics in South Africa. As Stephen has noted, one key demographic of particular significance here is urban sex workers.

The sheer volume of available foreign national healers, the saturation of the market, would seem to suggest that the majority of these doctors have not undergone any significant amount of training, whether as diviners and spiritual healers or as (perhaps more biomedically palatable) herbalists. From personal experience and from reading many of the safari pieces mentioned above, many such healers seem to rely on something like the famous ‘candle trick’ of exploitative root-workers in the US, where clients are given small free or affordable remedies and treatments on their first visit, but are subsequently told that they are badly spiritually afflicted upon their return, and need to shell out for much more elaborate and expensive procedures upon their return (see here and here for sample online lists by root-workers in the US describing signs to watch out for to avoid scammer or charlatan diviners and healers).

Given South Africa’s current health challenges regardless of how seriously one wants to take the country’s thriving economies of traditional healers and curers, the fact that these practitioners are often providing first-line treatments for clients’ HIV/AIDS symptoms and sexual health problems means that they must necessarily be appraised carefully as part of contemporary South Africa’s medically pluralist landscape and current public health crises.It’s certainly tempting and understandable why one might want to reduce the conversation about these healers and their flyers to Roper-style hand-wringing on the gullibility and desperation of the masses or to time-honoured discussions about masculine fragility and penis anxiety (and gross exploitation by tradition healers and herbal product manufacturers are very real) but there are clearly many reasons to pay attention to these practitioners beyond merely using them as material for a quick laugh or desultory head-shake.

- For readers who would like to learn more about the interactions between South African traditional healers and South African Pagans mentioned above, I recommend taking a look at this excellent article by Dale Wallace, a fantastic scholar of religion and Paganism in SA, who has been studying interactions between different kinds of ritual specialists in the country for decades.

Pingback: Celebrity Shamans and the Question of Indigenous Knowledge: A Review of, and some stray Reflections on ‘Inyanga: Sarah Mashele’s Story’ | A Perfumed Skull

Pingback: Tibet, the Role Playing Game: Table-top Anthropologies and Competing Knowledge Jurisdictions | A Perfumed Skull