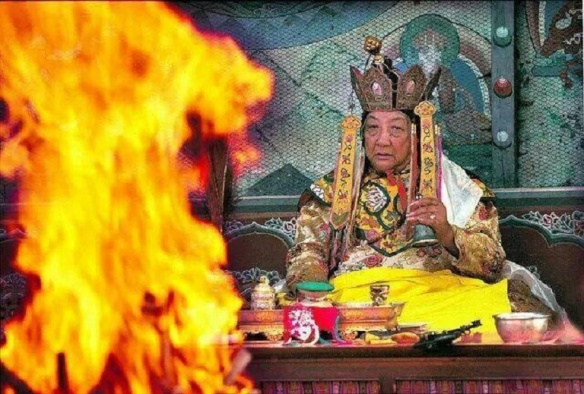

(A regal-looking Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (1910-1991), with tantric ritual bell or dril bu, seated behind a sbyin sreg or ‘burnt offering’ fire)

As a follow-up to my recent translation of Dr Nida Chenagtang’s chapter on how mantras work, I decided to translate a subsequent chapter in Dr Nida’s Mantra Healing book which deals with the ritual tools and substances most commonly used by ngakpa/ma. Dr Nida la gives a brief summary of some of the most salient ritual implements and objects used by mantra-healers and tantric wizards, and describes their functions, rationale, and construction, along with rules for their proper handling and use. The subject of ritual tools necessarily ties in which more general, theoretical reflections I have made on this blog about the role of materiality in magic and religion. How ought we to understand the status of magical, blessed or powerful objects or materials, in a Buddhist context where nothing that exists has any innate or enduring substantiality on the ultimate level, or for that matter where subtle, ‘imagined forms’ may be just as ontologically real, agentive, and efficacious as gross, material ones? As we saw in Dr Nida’s earlier chapter about mantras’ efficacy, the ultimate emptiness of phenomena is in fact directly related to their functionality or agency – it is precisely because material things are impermanent, compounded and conditional, that they are able to be transformed, and to transform in kind. Buddhist notions of dependent-origination and emptiness are wholesale dispensations that apply across divides of body-and-mind, real-and-representational, which are themselves also categories that operate quite differently in Buddhist philosophical contexts versus non-Buddhist ones.

It should be clear that the doctrine of emptiness undermines any sort of rank materialism, or reification or fetishizing of objects and concepts. At the same time, the body and the senses are central to Indo-Tibetan tantric philosophies and systems of practice. Ritual and contemplative engagement with sensory objects, and the progressive refining and transmuting of sensuous experience is pivotal to tantra’s relationship with the creative imagination, and lies at the heart of its self-transforming and self-divinizing agenda. In the opening of his chapter, Dr Nida reminds us that notwithstanding Buddhism’s admonitions to not become fixated on conventional concepts or material forms, genuine tantric virtuosi should nonetheless be ‘as rich as kings’ when it comes to tools and the trappings of their trade. The qualified ngakpa or ngakma has lots of tools because he or she knows how to use them skilfully as ‘props’ ‘supports’ or ‘stable connections’ (rten) that link with and influence other conditions and phenomena. The attentive reader will notice the extent to which the tantric-mantric tools described in Dr Nida’s chapter serve a kind of mnemonic purpose – through each tool’s form, colour, symbolism and so on, each of which operates on a range of levels, the practitioner is reminded of key truths and cosmological principles, and the tool becomes a meditative support for powerfully concentrating on these realities (this mnemonic function can extend to attached body parts as well, as can be seen in Dr Nida’s discussion on the significance of ngakpa’s dreadlocks).

Body-speech-and-mind are thus always and already integrated when it comes to ongoing, embodied ritual practice. In line with this idea, scholar of Hindu Tantra Gavin Flood points out the way in which the tantric body is something produced and refined through continual practice:

“…the tantric body is not a given that is discovered but a process that is constructed through dedicated effort over years of practice. … Any distinctions between knowing and acting, mind and body, are disrupted by the tantric body in the sense that what might be called imagination becomes a kind of action in tantric ritual and the forms that the body takes in ritual are a kind of knowing … This corporeal understanding shows itself in the great emphasis on transformative practices in the tantric traditions, ritual inseparable from vision, the body becoming alive with the universe within it, and vibrant with futurity in the anticipation of the goal of the tantric paths.”

(More on Flood’s book here. For further worthwhile reflections along these lines, see Phil Hine’s two-part essay on ‘the tantric body in practice’ over at his blog enfolding.org)

Notwithstanding this integration between body-speech-and-mind, as I discussed in this post about controversies surrounding the practice of sexual yoga with a physical versus imagined partner in Tibetan tantra, there remains some tension and debate about the extent to which (and the times when) external tools and ‘literal’ substances and procedures are indispensable, or may be substituted with inner, imagined ones (I say literal here rather than ‘embodied’ because I reckon it would be misleading to refer to ‘imagined’ processes as ‘dis-embodied’ or wholly ‘immaterial’). In a post entitled ‘Transcending Tools – More Like Misunderstanding Them’ professional sorcerer Jason Miller responds to practitioners of Western ritual magic who sometimes claim that one can or should ultimately outgrow magical tools, and discusses the different ways in which tools are and aren’t non-negotiable in both Tibetan tantric and Western ritual magic contexts.

‘Western’ occultists are not the only practitioners reflecting on the relationship between inner cultivation and outer ritual trappings. Jason’s post, and Dr Nida’s chapter remind me of something a ngakpa in Mcleod Ganj said to me about ritual tools a little while back. The ngakpa explained about how ngakpas from Khampa lineages (i.e. from the Kham region of Eastern Tibet) were often more flashy – they tended to keep long, elaborately styled dreadlocks and to sport more ornate jewellery and tools compared to ngakpa from other areas (such as Dingri, which is right on the Nepalese border, and happens to be this particular ngakpa’s hereditary lineage). The ngakpa explained how his Khampa teacher had had some very fancy patterned cloths and other objects he used as part of spirit traps to snare demons, but noted that the current senior ngakpa in town (who is also from Dingri) often performs the same rites with a comparatively unimpressive, dirty-looking rag. Both teachers got results, and both were powerful though. The ngakpa made an analogy, ‘It’s like if you have a knife – it doesn’t matter if your knife is dull, unless you want to cut someone, ha ha. With a ritual knife [or, as we shall see below, what’s called a phur pa], that can be dull – what really matters is that your mind is sharp!’. He then went on to suggest that he was a flexible and resourceful ritualist because he had studied with ngakpa from many different regions, and so wasn’t too thrown by having to adjust procedures or up/downsize ceremonies when circumstances required it, because he’d studied many styles from many masters.

These ethnographic reflections alert us to the fact that ritual procedures and tools are as much about regional histories and styles, as about philosophies of mind and materialism. At the same time, we shouldn’t over-emphasize the external-internal divide when it comes to Tibetan tantric ritual. As Yael Bentor has shown in her excellent overview, Tibetan yoga practices of inner heat and bliss involving the subtle channels, winds, and drops represent clear examples of the internalization of earlier standard, external fire rituals from India. In this inward progression, the offering fire becomes the heat generated in the body through austerities and the manipulation of breath and vital-force; the hearth is the junction of three channels, the offering ladle becomes one of the side channels, the skull is the offering cup, and so on. It would be wrong to assume, however, that because external immolation rites have been internalized and have become a part of elaborate and valorized psycho-physiological spiritual disciplines that external fire pujas must somehow be redundant. To the contrary such rites, called sbyin sreg in Tibetan remain a crucial component of tantric practice and continue to be relied upon alongside forms of yoga that can be seen as interiorizations of them. Frameworks like ‘outer, inner, secret’ and ‘body, speech, mind’ provide mechanisms for integrating levels and registers of perception and experience, and for resolving tensions between them.

(One of Dr Nida la’s Mantra Healing teachers, Khenchen Troru Tshenam)

The idea of external-internal continuities and tools as triggering, mnemonic aids re-surfaces in Dr Nida’s brief comments below on ngakpas’ use of crystals. I especially like this section. Not only does Dr Nida introduce crystals’ use in Dzogchen teachings as a kind of teaching-aid for pointing out the nature of mind, but we also learn about crystals’ strong links with dream practices in Tibetan traditions as well. While the use of ‘cool’ crystals to treat hot, feverish conditions is a traditional one which Dr Nida learned from his guru Khenchen Troru Tshenam, the practice of putting heated crystals on points of illness came to the Doctor in a dream-vision which he received during a mantra retreat. If nothing else then, this short section is a reminder that the use of crystals for healing and as aids for magic and meditation is not limited to contemporary New Age contexts. The use of crystals for healing and in rituals has a much longer and more diverse history (both in Tibetan and Western esoteric contexts) than just the New Age crystal industry and now quasi-scriptural books such as Melody’s Love is in the Earth. We see that Tibetan ngakpa have used crystals (and have had long ‘spiritual’ hair, for that matter) for centuries, and, continue in the present to discover new ways to use them as a part of magic, meditation, and medicine. Take that, hippies.

There’s a lot to say about Dr Nida’s chapter and its many interesting details, but I’ll leave off here and let you read it instead. Enjoy!

(*I did a very rough translation of some of the Tibetan materia medica Dr Nida mentions. I unfortunately did not have a good Tibetan-English lexicon of Tibetan medicines at hand while translating, so the list is only partially translated. I’ll try to fill in the gaps a bit later)

Chapter 6: The most necessary kinds of implements and ritual substances for Mantra Healing

It’s generally said according to the customs of Tibetan mantrins that “the genuine ngakpa ought to be as wealthy as a king”. Because the powers of mantras and ritual substances need to be combined together, ngakpas require a great many implements or belongings. The genuine ngakpa has need of many things, including samaya or sacramental tantric vow substances; sil snyan, or medium-sized cymbals; drums; a gshang or flat ritual bell; sbug chol or larger bell-metal cymbals; a dorje or vajra; a tantric bell; a damaru or double-headed hand-drum; rosaries; a khatvanga or three-pronged trident; conch shells; flutes; rkang gling or human thigh-bone trumpets; ladles (for fire offering rites); ritual vases; fabrics to sit on, as well as different kinds of ingredients, such as plant medicines and mineral or ‘treasure’ substances [the gter here could equally refer to mineral compounds or to blessed or relic substances that are placed in containers and buried or thrown into lakes as blessings and propitiatory offerings to spirits], parts of animals and different kinds of medicinal and otherwise indispensable mantra substances. Because so many doctors in ancient Tibet practiced medicine-and-mantras together, they made full use of both medical and mantra/tantric ingredients. While I fear (I cannot) here explain in this text ritual substances and accouterments in their entirety, I will introduce (in what follows) some of the most indispensable and commonly used items.

One: Rosaries

The so-called rosary or phreng ba [pronounced ‘treng-nga’, ‘treng wa’ and which literally means a ‘string’ or series of some object] is symbolic of mantras ‘stringing along’ or fascinating the mind (sngags la yid phreng ba). Its primary function is to keep measure of however many mantras are recited. The efficacy of specific mantras is extended through the dependent links of (rosaries’) colour and the number of (recitations counted). There are many different kinds of rosaries – the chief ones among these are differentiated (as follows):

Mantric action: Rosary material: Rosary colour:

Pacifying White sandalwood and White

ivory

Increasing Bo nghi tsa, a ru ra (fruits), Yellow/gold

gold

Magnetizing seng ldeng (a kind of acacia), Red

lang thang (kind of henbane?),

mdzo mo tree (caragana tibetica),

coral, red sandalwood

Subjugating Metal (iron), raksha seeds, Green and blue, black

turquoise, thorn tree

Reciting a count of seven, twenty-one, sixty, or one hundred and eight beads of a rosary is important. Some mantras need to be recited seven times, twenty-one times, or one hundred and eight times, after which the power of their dependent connection arises.

The rosary consecration mantra is as follows: OM RUTSI RA MA NI PRA VA DHA NA YE SVA HA [Tibetans also tend to say OM RUTSI RAMANI TRAWA TAYA HUNG].

Rosary cords ought to use two threads or else five woven together. If the cord is too fine, one will have obstacles, if it’s (too) thick, there won’t be any siddhi [i.e. spiritual accomplishments]. If the cord gets severed, one must replace it immediately before the day is over. If rosary-beads are damaged or missing mantras won’t be efficacious, and so one must replace the rosary with a new one. It’s better to have new rosaries than to keep old ones, and it’s best if each person has their own individual rosary for reciting mantras. Very holy ngak-chang lamas, rather than keeping used rosaries at home, (say that) it’s better if, rather than using them for counting, one fastens them around one’s neck for protection.

Regarding rosary samaya or tantric oaths: the power of mantras enters into ngakpas’ tongues and breath and once they’ve finished reciting mantras and their breath has hit the rosary, a part of the mantras’ power is absorbed into the prayer beads. For this reason, the rosary is the primary mantra power-containing implement. Accordingly, one must maintain pure tantric vows with one’s rosary. A rosary which possesses mantra power should be like the rosary of Chögyal Ngawang Dargye – when he was cremated he had his rosary around his neck and his body didn’t burn, for example.

One should not allow one’s rosary to pass into other’s hands, one should not let it be seen by the eyes of other people. If it’s kept inseparable from the warmth of one’s own body, it will have positive efficacy, and will benefit one’s bodily constitution. One should not let dogs or rodents step over it, one shouldn’t flaunt it to people or let it become infected with impurities. One should not use it for divination or blessing either [i.e. one’s primary rosary used for regular religious practice – reciting the mantras of the three roots, the guru, meditational deity, and dakini and so – should not also be used for blessing, healing or divinatory procedures. One or more separate rosaries are kept for this purpose].

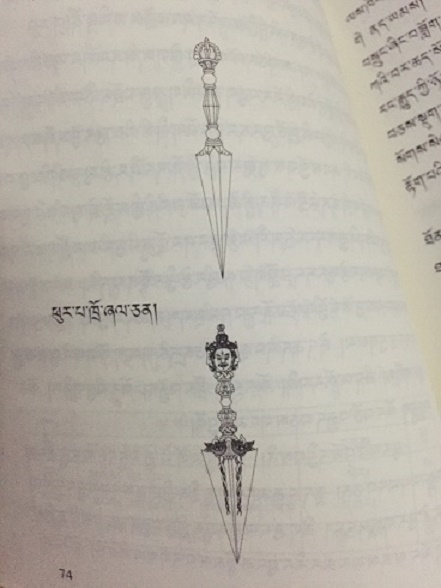

Two: phur pa, or three-edged tantric ritual dagger or stake

Kilaya in Sanskrit and phur pa or phur bu in Tibet, this is in essence a wrathful implement that symbolizes the magical power (nus stobs) of the (enlightened) activity of the Transcendent Conqueror, the Great and Noble Dorje Shönnu or Vajrakumara, who exemplifies the non-dual emptiness of the manifestations of Samsara-Nirvana. In Tibetan Buddhist lineages, out of the many implements of the Secret Mantra that exist, the most important implement for dissolving obstacles, sicknesses and demonic provocations is the phur bu. It is a tool which accomplishes the four magical activities of pacifying, increasing, magnetizing and wrathfully subjugating with ease.

The phur bu is extremely necessary for mantra healing, and for this reason it is taught in many mantra compilations that a phur bu of four inches made of acacia (seng ldeng) and of skyer wood (berberry?) and so on, is definitely required. A great many different kinds of obstacle and disease vanquishing phur bu are differentiated according to their materials, colour, length and shape, in line with the (enlightened) perspective of the classes of Tantras, but here (I will content myself with addressing), from among the root-categorizations, the phur pa for (each of) the four magical actions, and the phur pa of good/spiritual qualities (yon tan gyi phur pa).

The four phur pa of the four kinds of (magical) activities are: the white-coloured pacifying phur pa with (a hilt with) a vajra-end and round foot; the yellow-coloured increasing phur pa with the precious (jewel)-end and crescent foot; the magnetizing red-coloured phur pa with a lotus-end and crescent foot; and the subjugating green-coloured phur pa with a crossed vajra-end and triangular foot.

Here’s a chart showing the materials, colours, and ritual activities associated with (each) phur pa:

Activity Phur pa material Colour Element

Pacifying Silver, aluminium, white sandalwood White Water

Increasing Gold, acacia Yellow Earth

Magnetizing Copper, mdzo mo tree, bswe tree Red Fire

Subjugating Iron, thorn-bearing trees Green/black Air

The seven good qualities phur pa are 1) the phur pa of the ten wrathful ones that ‘severs the boundaries’ [i.e. evil spirits] 2) the chief phur pa that (does) as commanded 3) the phur pa of the messanger-envoy 4) the phur pa of the activities of striking 5) the phur pa that is inseparable from one’s own body 6) the phur pa that protects the abodes and 7) the phur pa that brings the oath-bound protectors under one’s control. These are connected with the mandala of the meditational deity or yid dam Dorje Phurpa or Vajrakilaya.

The way these are made is as follows: one cuts clean wood (from a tree growing) in clean soil and in a good location (on the map, geomantically etc.) and puts it inside a precious container, after which one must say the one hundred syllable mantra and make bsang incense and torma offerings. ‘Primary phur pas’ should be made from the middle part of the wood, and ‘(ritual) action phur pas’ out of the top and bottom parts. Mainly, there is a very strong dependent link between constructing the phur pa’s head in the direction of the foot of the wood and the phur pa’s foot (in the direction of) the wood’s end, and (the magical actions) of protecting against and turning back (negative forces). While reciting Vajrakilaya’s mantra, the phur pa maker should display the phur pa in an easterly, southerly, westerly and northerly direction in line with the four magical actions of pacifying, increasings, magnetizing and subjugating, and should display the phur pa’s point inwardly for protective actions and outwardly for turning back or exorcistic ones. They must make it from whatever copper-metal is appropriate and should recite the mantras uninterruptedly without getting the directions wrong. One must absolutely refrain from making the phur pa either too thick or too fine, from making snapping its waist, from making it square or with cracks, and so on. The phur pa should be four, six, eight, twelve, sixteen or eighteen inches in length, whatever is required.

Regarding the phur pa’s shape: the upper-part has a knotted head, the middle-part has lotus petals that fit within (the wielder’s) hand, the crossed knot of the lower-parts has the head of a chu srin or mythological water-monster [the Sanskrit Makara – the Tibetan word has come to mean a crocodile in more contemporary, secular usage, but traditionally refers to the monstrous water-goat of the constellation of Capricorn] from whose mouth wealth/splendour (dpal) pours out. The lower point is triangular and the edge is ornamented with a crossed-knot. The length up from the chu srin in the middle to the head at the top, and the length from the chu srin down to the tip must be equal. For example, with a phur pa of eight inches, the lower part and upper part should (each) be four inches. The system of the Tantras has phur pa without wrathful faces and the Treasure tradition has phur pa with wrathful faces – these mostly come from Tibet [i.e. and not from India, like the principle tantras].

[Illustration: phur pa without a wrathful countenance

Phur pa with a wrathful countenance]

The phur pa functions on an outer, inner, and secret (level). It dissolves defects of the outer environment of the external world and protects against and turns back harm to the natural realm, famine, epidemics, earthquakes, floods, fires, war and so on. It dissolves the suffering of sickness of the psycho-physical aggregates of the human body and obstacles to one’s life-span and activities. It dissolves defects of inner mental unhappiness and purifies the root of the suffering of the afflictive emotions of one’s mental-continuum: ignorance, desire, aggression/hatred, confusion, and arrogance, and cures an unhappy heart, madness, seizures and so on. On the secret level, it conquers (dualistic) subject-object discursive thought and (allows one) to penetrate the meaning of non-conceptuality.

Effects are also gained by looking at, carrying, and keeping phur pas in one’s home. If one gazes at (a phur pa) the cross-knot head vanquishes the five poisons, the wrathful (deity) of the phur pa’s upper body vanquishes ordinary conceptual thought, and its lower edges purify the conceptual thought of the eight aggregate consciousnesses. The six tamed serpents grant fulfillment of the indulging of the six sensory faculties, by means of the three lower edges, all the works of malevolent (beings) and discordant elemental constituents are slain and liberated. If one carries a phur pa on one’s person it (will act as) an amulet and will grant one happiness of body and mind and keep one free from infectious disease and adverse circumstances. Placed in one’s home, it will protect against brigands and thieves, will bring accord to the people of the household, enlarge riches and increase auspiciousness and potential – as such, the (physical) ‘prop’ or ritual ‘support’ (rten) of the phur pa should be cherished as a wish-fulfilling jewel.

Three: Vases

There are two vases, ‘accomplishment vases’ and ‘action vases’. Of these two, the accomplishment vase is defined as a symbol for the yid dam or mind-bound meditational deity and its siddhis or spiritual powers, who during the deity-sadhana (resides) in the centre of the mandala. The action vase is the vase meant for blessing, for giving vase-water and doing ritual ablutions. It is used in the service of bringing in-the-flesh benefit to those who are ill, have obstacles and are beset by demons. On the vase’s lid there are objects like kusha grass and peacock feathers. Kusha grass is a kind of grass praised by Master Buddha for its positive constituents and which has the power to dissolve obscurations/pollution. Since it has a special power to cure disturbed elemental constituents and dissolve impurities, and so on, if one inserts kusha under one’s pillow during empowerments or in the context of dream analysis, and so on, one’s dreams will become clear. The kusha grass at the lip of the vase is also there for the purpose of purifying obscurations and impurities. As for the peacock feather: the peacock is a bird which has the power to eat poison and its feathers have the intrinsic power to cure poisoning and the poisons of sickness. These are very important for curing poisons in the context of mantra healing, and (they are also used) in specific rituals for casting out diseases.

Crystals – because these have the in-born power of coolness, they have the benefit of cutting through fever. Because they have the power to produce brilliance and clarity (dwangs pa’I ‘byung nus) they can dissolve things like mental fogginess, dullness, and the clouding of rig pa or innate, primordial awareness. In the Great Perfection tradition, crystals are used as analogies for rig pa in the pointing out of mind (teachings), and they are able to reveal, solely through their example, the natural state of mind to which they are equivalent (in qualities). If one looks directly at (a crystal) one’s mood (‘mental field/constituents’) is made lucid and bright (dwangs pa). There are also visualizations like the one in the context of dream-accomplishment where one meditates on one’s own body as (being made of) crystal, and as covered with eyes.

How crystals should be used during treatments: specially placing a cold crystal on (areas of) fever will heal such sickness. Also, I had a dream-vision (in which it was revealed that) one can, in accordance with hot and cold disorders, heat up the smooth point of a crystal about the size of one’s thumb [i.e. the space between the top of one’s thumb and the tip of one’s index finger] in a fire (and then, after) it becomes hot, one can then apply it [i.e. as a hot compress] on sick and painful spots.

Four: The Vajra and Bell, and rkang gling or Human thigh-bone trumpet

Generally speaking, when ngakpa (who practice) the Vajrayana hold the vajra and bell it’s so as to recall great skillful means and the very nature of empty wisdom. The vajra and bell symbolize the nature of the bodhicitta of ultimate truth, indivisible bliss-emptiness. Representations of the bodhisattva, the vajra and bell exemplify skillful means-and-wisdom.

The vajra symbolizes immutability and (different vajras) of three, five, nine, and crossed prongs are used for (each of) the four actions of pacifying, increasing, magnetizing, and subjugating. In brief, the vajra is a symbolic manifestation of unparalleled means and the bell of the basic space or dimension of the Mother-Queen, the emptiness of the ultimate reality of dharmadhatu. Thus, together they symbolize the inter-penetration of means and wisdom. Tibetan ngak-chang bless patients so as to cast out demonic impediments (bgegs) and pacify obstacles and it is taught that the purpose of the large human thigh-bone trumpet and copper pipe, and the other flutes composed of various materials is to summon magical powers (dngos grub) and blessings, and to cast out gdon and bgegs demons. Thus, yogis, gcod practitioners and ngakpa bless patients by means of human thigh-bone trumpets. There are a lot more elaborate descriptions (I could provide on these) but this is as much (as I will say) here.

Five: A list of medicinal substances

In general, mantras can be said over all of the different kinds of medicinal substances found within Tibetan traditional medicine. While there are a great many different sorts of medicinal substances this is a list of some medicinal substances that are regularly used specifically in the context of mantra healing:

For kinds of herbs: frankincense, black and white mustard, ‘the great medicine’ [a species of black aconite], a ru ra [myrobalan], nutmeg, asafoetida, saffron, cardamom, bamboo pith/juice, cloves, ‘pure water’ chu dag, sandalwood, acacia, black barley, aconite/wolfsbane, ‘tiger’s flesh’ [oxytropis falcata], deer musk, sgo skya, neem/tamarisk, lcam pa, pomegranate, ‘bird’s foot’[Delphinium species], ‘straight vajra’, ta hrig, birch, turmeric, ginger, ‘Chinese/Indian salt’ [sal-ammoniac], seng throm, chu ma rtsi [polygonum sibiricum], ru rta [Costus speciosus root], bamboo shoot, byi tang ka, camphor, hellebore, ug chos [the incarvillea compacta flower], amalaki, ‘golden fire’ flower, rhododendron, liquorice.

For animal parts: an eight-year old boy’s urine, weasel meat, dog fur, the faeces of a black dog with a white (patch of fur) on its chest/heart, the dung pellets of a rabbit, deer-musk, the bile/gall-bladder of a bear, horse’s blood, horse’s eyes, blood from the underbelly of a goat, bull manure, scorched cow horn, butter and milk, butter-milk, a white sheep’s winter wool

For kinds of earth and stones: incinerated boulder (dust), sulphur, realgar [arsenic sulphide] and various sorts of liquefied rocks.

This is a general description of the different sorts of substances that are taught in the mantra compilations.”

.From ‘The Science of Dependent-Origination Mantra Healing’ (rten ‘brel sngags bcos rig pa), written by Nyida Heruka and Yeshe Drolma, 2015, mi rigs dpe skrun khang, pp. 69-79..

Pingback: The White-Robed, Dreadlocked Community: Dr Nida Chenagtsang’s Introduction to and Defense of the Ngakpa Tradition | A Perfumed Skull

Pingback: Linkage: Sigils, mantras, and daisies | Spiral Nature Magazine

Pingback: Common Tools and Substances Used in Mantra Healings – Zero Equals Two!