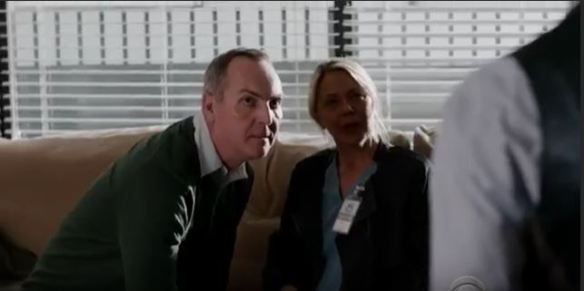

(Left-right) Clara Seger (Alana De La Garza), Unit Chief Jack Garrett (Gary Sinise), Russ “Monty” Montgomery (Tyler James Williams), Mae Jarvis (Annie Funke) and Matt Simmons (Daniel Henney) comprise the International Repsonse Unit, the FBI division at the heart of the upcoming drama series, CRIMINAL MINDS: BEYOND BORDERS, which premieres Wednesday, March 2 (10:00-11:00 PM, ET/PT) on the CBS Television Network. The IRT is tasked with solving crimes and coming to the rescue of Americans who find themselves in danger while abroad. Photo: Richard Cartwright/CBS é2015 CBS Broadcasting, Inc. All Rights Reserved

A friend of mine recently alerted me to the existence of a new TV show that is a spin-off from CBS’ popular crime-procedural series Criminal Minds. Criminal Minds: Beyond Borders, which kicked off in March this year, presents us with the amazingly un-ironic spectacle of a Criminal Minds-style team of American profilers and crime experts gone global. This diverse (yet still deeply patriot) team is headed by series veteran Gary Sinise/Jack Garrett, and even has its own fucking jet, by means of which it flies, Team America-style around the world to save US citizens who’ve been so stupid as to actually travel outside of their own country. Here’s the series trailer:

In an opening voice-over at the start of each episode we learn that:

“Over 68 million Americans leave the safety of our borders every year.

If danger strikes, the FBI’s International Response is called into action.”

It’s clear then, that the show’s primary audience is US citizens, and one would assume, those citizens in particular who have to date never left the country.

So far, the show has treated viewers to chilling scenes of Americans being kidnapped, having their organs harvested, and a whole other litany of world-out-there horrors. A recurring theme in the show is the heavy-handedness, corruption or ineptitude of local police, governmental, and military forces, and the superior organization or logic of US officials. A week or two ago on the 11th of May, the tenth episode of the pilot season of the show aired. IMDB’s plot keywords for the episode – ‘electric torture’ ‘bare chested male bondage’ and ‘bare chested male’ – are provocative enough, but, as we shall see, the name of this episode, Iqiniso, an isiZulu word which means ‘the truth’ or ‘certainty’, is especially suggestive. IsiZulu is the most widely spoken first-language in South Africa, and the episode is, accordingly set in that country.

Iqiniso opens with a predictable montage of giraffes, savannah, and local musical flavour, after which we are introduced to two conventionally handsome white all-American college students, Brandon and Timothy Smit, brothers who are bar-tending at a club in Johannesburg. As the boys close up the bar for the night, we learn their place of employment is run by their paternal aunt Aunt M, a native Afrikaans-speaking white South African with whom they have come to work and live in-between semesters. The two brothers express their great pleasure at their aunt having let them come and visit. If it wasn’t for her, they explain, they’d still be “stuck somewhere in the middle of Georgia bulldozing dirt for Dad’s company.” Aunt M goes off to bed and the boys finish up. In some heavy foreshadowing, Brandon says to Tim that he gets why their Dad moved away from Johannesburg, but not why he never wanted to come back to visit. Tim goes out back to take out the trash. Brandon hears a crash from inside, grabs a gun that’s under the counter and goes out to check on his brother. Brandon discovers Tim knocked unconscious, and then he himself is kidnapped by, well, by this:

So yeah, a person wearing an animal skull with ping pong ball eyes with a weave attached to it, as far as I can tell.

Cut to the International FBI jet and Gary Sinise gets us up to speed on what has happened. Tim’s corpse has been found in a (fictional) shanty town outside of Johannesburg called ‘Azaria’ (Azaria appears to be a sort of hyper-demonized Soweto). As we see liberally displayed in pictures, his body has been covered in animal skins and daubed with white clay. His tongue has been sliced, there are claw-like marks on his body and a wooden stake has been driven through his skull. His brother Brandon’s whereabouts and condition are unknown. We learn that Tim’s ritual murder is reminiscent of other killings and staging of corpses that have taken place previously in and around Azaria. Agent Clare Seger (played by Alana de la Garza) provides viewers with some quick cultural background:

“You know, the desecration of these bodies, it’s very specific.

Bodies caked in white clay, spikes driven through foreheads, tongues severed.

It’s derived from a rare Southern African divining practice, which is meant to represent umkovu, which are basically corpses that have been dug up and revived by a shaman in order to do his bidding.”

Her colleague, Mae Jarvis (played by Annie Funke) retorts, “So you think our unsub believes that he’s recruiting his own zombie soul brigade?” Agent Seger shrugs, but like, in a way that tells us this is totally a reasonable thing for us to think. Jack then informs us that the South African Special Forces Brigade have taken control of the case. Apparently seeing nothing but sharpness in her own approach and surroundings, Seger suggests that “paramilitary tactics are a bit of a blunt instrument, don’t you think?” Jack explains that that may well be why the US ambassador and SA foreign minister have called them in.

To the writer Erica Messer’s credit (maybe) it does not turn out that our unsub is an evil third-world sorcerer intent on making a zombie army. Granted, as the episode unfolds we are indeed treated to a fair amount of ethno-bongo bongo paranormal kitsch. Making good on those keywords, Brandon is repeatedly shown shirtless, being tortured by Ping pong ball eyes, who says in a distinctly non-native sounding voice some choice ritual refrains in isiZulu “Igazi! Wena ungufakazi wami! Iqiniso!” (Blood! You are my witness! The truth!). Jack is also reunited with a black South African detective he worked with before, who we learn is herself a shaman and more than once in the episode attempts to commune with the spirits of the recently deceased. As I showed in another post, the South African police force does in fact have its fair share of occult crime specialists, and more than one spirit-medium-detective actually exists in the SAPS.

The story ultimately pans out like this (SPOILERS). It turns out that Brandon and Tim Smit’s ex-pat Afrikaner father Armand (played by veteran ‘we-need-a-white-South-African-male-quick’ actor Arnold Vosloo) is actually an ex-Apartheid-era special forces criminal, a former member of a covert task force called ‘Pretorius’ that was developed as a response to the ritual murder of a white female police officer called Miller by a black anti-Apartheid activist. The white Afrikaner military men who formed this unit tortured and murdered fourteen anti-Apartheid activists before the fall of Apartheid, but were granted amnesty/immunity by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1995, and their names were not publicly released. The truth, however, is that the murder of the white police officer was a false flag operation. Armand and his Pretorius buddies planned the murder, and made it look ‘Zulu’ so that they would have an excuse to form their task force and kill black activists. Ping pong ball eyes is the white Afrikaner brother of the policewoman who was killed. He has been torturing and killing the children of Pretorius members and staging their murders to resemble the original staged ritual killing of his sister out of revenge, and so as to expose the truth. Armand Smit refuses to admit his complicity until the very end, and it is only through his largely oblivious American wife that the Criminal Minds team discover the name of the one last unidentified Pretorius member. The team is able to make it to this member’s house to confront (and ultimately kill) Ping pong ball eyes before he can murder the Pretorius member and his pregnant daughter. Brandon is rescued from the abandoned warehouse dungeon where Ping pong ball eyes has been keeping him and reunited with his family. A smug Arnold Vosloo is arrested for the murder of Ping pong balls’ sister. In the closing seconds of the episode the team pose facing the camera in a hallway like on a poster, and Jack declares that justice “may have been delayed but [it] wasn’t denied.”

It’s hard to know exactly what to make of this all as a South African viewer. The overarching imperial moral of the show – that the legal, political, and moral quandaries of other countries can and should be solved through the sage and saintly intervention of US authorities – is reiterated in many ways throughout the episode. The show’s scare-tactics are clear. In one scene, US agent Montgomery is questioning Armand Smit and his teary American wife. Before Montgomery learns the truth about Smit’s past, he consoles him and tells him not to blame himself for what has befallen his son. Pursuing the local gang intimidation lead the team have been considering he asks the couple if their sons were ever ‘hassled’ by local gangs. “No, why?” asks Mrs Smit. “Nothing specific”, says Montgomery,

“we just have to evaluate every possible threat.”

This line sums up the show’s own dark witchcraft, its mandate of instilling maximum paranoia in its home crowd.

When the mutilated clay-covered body of the son of a different Pretorius member is discovered in a warehouse in Azaria, Jack and the head of the SA Special Forces travel to the shanty-town. General Zwane (played by Mykelti Williams of Forrest Gump fame) informs the US team they cannot come, since this area of Azaria is basically a war-zone, which SA police have ‘ceded’ to local gang lords. Detective Doshi is allowed to come because she can speak with the dead, and she allows Jack to tag along. The team ride in in armoured vehicles, and the second they step foot out of the car, they are fired upon by hired gang members who have been instructed to kill them on sight. Zwane tells Jack Garrett he can only hold the perimeter for a short time, so he must investigate the murder scene quickly – because, blood-thirsty gangsters will mow you down in seconds in South African shanty-towns, even if you are military in armoured tanks with big, big guns, or something. The scenes after the failed assassinations, where Jack and Ananda investigate the corpse present us with a startlingly iconic image. The white Afrikaner male victim is trussed up, Christ-like, an unwilling martyr to the sins of the past – light pierces him from all around as it shines through a hundred bullet holes perforating the tin and crumbling mortar ruin of the shanty-town.

(A Bullet-hole cathedral to white South African male victimhood? That, or just really neat scene design!)

Watching this I had a similar reaction to what I felt watching District 9, South African director Neil Blomkamp’s 2009 internationally successful science-fiction thriller set in South Africa. Images of Kaspers (the local name for the armoured security vehicles which were used during Apartheid against black ‘terrorists’ in the townships), the dramatic conflation of police and military in cinematic South Africa, propose a present-future South Africa which looks and feels an awful lot like an earlier one – namely, the South Africa of the mid 1980s, of my time of birth, of bloody military emergency, of an unprecedented number of extra-judicial arrests, murders, and torture of South African citizens who opposed the regime.

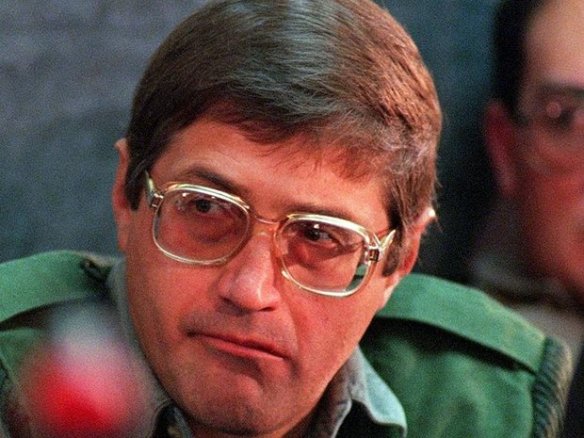

One part of me wants to object to this collapsing of history, to Hollywood’s unwillingness to ‘properly’ periodize South Africa’s history. But then, as so many contemporary South African activists have pointed out, very little has changed on a socio-economic level in the Rainbow Nation since the formal end of Apartheid in 1994. Despite the mangled accents and weird character names, there are moments in the Criminal Minds, Beyond Borders episode which ring fairly true. There really are American bros who work at bars while on holiday, umkhovu is a word that is used in isiZulu to refer to a sort of zombie-ish necromantic familiar made and sent by witches. Erica Messer writes Arnold Vosloo’s Afrikaner ex-pat character convincingly. His lines about ‘just wanting to protect his family’ about ‘not wanting to return to that godforsaken place’ about seeking ‘a better place’, his departure from the country in the early 90s, and the general tone of his interactions with black American agent Montgomery present a picture of white flight and fragility, of investment in a narrative of supposedly uniquely white persecution post-Apartheid which any South African today would recognize. (Any South African would also probably recognize that Armand Smit and his fellow Pretorius members are clearly based on real-life Apartheid-era state-sponsored police colonel, torturer and assassin Eugene De Kock, who is popularly known in SA as ‘Prime Evil’. De Kock like Smit, operated a covert counter-insurgency group called C10. Like Smit, he testified to the Truth and Reconciliation committee in the 90s, but unlike Smit, he was sentenced thereafter to 212 years in prison. (As it happens, De Kock was granted parole last year. See here for a piece by Rebecca Davis from just yesterday, which discusses De Kock’s bizarre public appearance at a talk about a recent book that exposes his own crimes, which was held at an international Literary Festival in Franschhoek outside Cape Town).

(In addition to possessing ancient mummy blood-magics, Arnold Vosloo also has strong powers of White male South African indignation)

(Eugene De Kock, a.k.a. ‘Prime Evil’)

It’s worth reflecting on what kind of justice CBS is serving for South Africans though, is worth considering how the show’s creators have framed South Africa’s history in light of current and past events. At one point in the episode, agent Seger and agent Simmons (played by Daniel Henney), following up a lead, go to interview a black Mozambican South African former child-soldier called Paul Ntombi (played by non-Mozambican actor Dayo Ade) who is supposed to have ordered the hit in the shanty-town. Ntombi is in prison, serving a life-sentence for a host of crimes. It becomes clear that he knows who the masked killer is, and has some idea of why he is committing his murders. A heated back-and-forth ensues between Seger (who reads as white) and Ntombi:

Ntombi: [Chuckles] The thing is, I don’t want you to catch him. As far as I’m concerned, not enough Afrikaans blood has been spilled to make up for the blood of my ancestors.

Simmons: [Sarcastically] Yeah, I’d say you’ve really done your ancestors proud, killing and enslaving your brothers over drugs.

Ntombi: [Chains rattle] – Don’t you lecture me about my history. If it weren’t for Mandela, there’d be no need for Ibhuloho [the name of his gang in the episode]. If Madiba [Nelson Mandela] would have done what was necessary and exterminate the white devil, there’d be plenty for all my people.

Seger: And what, you think you’re the savior of all those left behind? Let me tell you something.

You are nothing but a parasite.

Ntombi: [Thud, chains rattle] I will tell you something. You want to know what this is? Hmm? “Helter Skelter.” The beginning of the end. There is a debt of blood out there, and I will tell you, my dear, payback is a bitch.

The last twelve months or so have seen student protests focused on the decolonization and democratization of SA campuses and society sweep across the country. Under the flexible and intersectional #MustFall banner, thousands of South African students have engaged in a range of protest actions that have sought to raise awareness about and transform South Africa’s still all-too-consequential legacies of colonialism and black disenfranchisement and disempowerment. Many of these protests have focused on the question of equitable access to education and the decolonization of South African campuses and curricula, under the twin #s of #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall. Recently, black South African activists Ntokozo Qwabe and Wandile Dlamini garnered significant media attention when they refused to tip a white server (or, in South Africanese, ‘waitresss’) in Cape Town, and wrote on their bill, “we will give tip when you return the land”. Qwabe related the incident on social media, and reported that the server, Asleigh Schultz, had burst into tears after reading the note. Furious, ‘decent’ South Africans denounced what they saw as the two’s (and especially Qwabe’s) cruelty and victimization of Schultz. To make up for Schultz’s perceived mistreatment, as part of a campaign, thousands of South Africans donated money to her in place of the tip she was denied. It was recently reported that Schultz now has enough cash to buy a house near her Mom’s place. Whatever you may think of the appropriateness or usefulness of Qwabe and Dlamini’s protest, or about this server’s feelings, the fact that what started as a small but widely-publicized act of protest about the colonial expropriation of black land and the issue of land reparations ended up turning into a campaign that transformed white fragility and white tears into cold hard cash – that then allowed an apparent white victim in post-not-quite-so-post-colonial South Africa to secure property and holdings, is preeeetty ironic (see an excellent sum-up here from Rebecca Davis again, on the current value of white tears in post-Apartheid South Africa). Further calls have been sounded for Qwabe to be have his Rhodes scholarship removed, and for him to leave Oxford University where he is a student.

It is significant then that, in this moment, Criminal Minds, Beyond Borders’ creators chose to portray black South Africans calling for redress of past injustices in the present as morally-bankrupt and dangerous criminals. Ntombi’s dissatisfaction with the current state of Mandela and Tutu’s post-apartheid Rainbow Nation is presented as a sort of lunacy of Charles Manson-esque proportions (in addition to the ‘Helter-Skelter’ Manson-family race war apocalypse reference in the Ntombi scene, at one point Ping pong ball eyes a.k.a. Curtis Miller is also shown terrorizing the extremely pregnant blond daughter of one of the surviving Pretorius members with the tongs of a sharpened rake. This directly recalls the gruesome details of the murder of Sharon Tate by Manson family members in 1969). At one point, agent Montgomery is complaining to agent Jack Garrett about Armand Smit’s refusal to admit his involvement in Pretorius. We are presented with the following exchange between the young black agent and his white superior:

Montgomery: And now we’re face-to-face with one of the men responsible for torturing and murdering 14 innocent people People who were just fighting for their freedom, and there’s not a damn thing we can do to bring them to justice.

Garrett: I know, but I think the best thing right now is to remember the sins of the father have nothing to do with the son. We need to stay focused on saving Brandon’s life.

Montgomery: [Sighs] – You’re right.

Given what’s happening in South Africa right now, this is not a neutral or casual sort of statement. The episode’s creators made an executive decision to avoid confronting the realities of black pain, disaffection and rage in today’s South Africa, and chose to focus on white pain and fears instead. When the idea of black rage and disillusionment is discussed, it is either shut down or demonized. Before he is eventually killed, Curt Ping pong balls Miller responds to Jack’s request to stand down, to stop hurting the ex-Pretorius member and his daughter, to let them bring this man to justice, by yelling: “you cannot punish these men, they are protected forever, so I will end them forever.” That position, we learn, gets you a stake through the guts.

The episode demonstrates for viewers both the right ways and the wrong ways to seek justice, and reminds us that neo-imperial agents of ‘Murkkah inevitably know which ways are which. We are shown few if any examples of people who want to talk about the unresolved horrors of the past and about justice in the present who are not crazy, criminal, or untrustworthy. Lieutenant Doshi, the psychic detective, is presented as a somewhat more complex character. She is allowed a number of long and professorial lines throughout the show (lines that open with things like “I do not subscribe to the Western dualism of physical versus spiritual…”) where she points out the Americans’ ethnocentricism, alerts them to an alternative African way. Her speaking with the dead and attempts to bring their truths to light, to bring them peace and comfort, represents another model for engaging with the ghosts of the past. Yet despite her more rounded and sympathetic treatment, she is still introduced to us first and foremost as a person to be concerned about, as someone unorthodox and potentially dangerous. Seger again plays a cool, rational, and sceptical (white) foil to black emotionalism and irrationality. As the team are going over the details in a Johannesburg police station, Doshi interjects:

(Seger’s ‘I-have-no-time-for-your-third-world-irrationality-face)

Doshi: You know what I find most fascinating about American criminal procedure? Is the obsessive fixation with applying logical motivations to inherently aberrant and impassioned behaviors.

Seger: [head propped up with one hand and elbow on the desk and looking up at Doshi, tone skeptical, mildly sarcastic] You would prefer that we apply a more emotional logic to our analysis?

Doshi: At some point, we must draw ourselves into the hearts and minds of these unknown subjects.

Garret: [Passionately, clearly speaking from his past experiences with Doshi] I disagree. That approach is self-indulgent and reckless.

Doshi: And why I would prefer the guidance of the dead.

(Doshi, literally standing for African values. That’s the South African flag hanging behind her, btdubz)

The themes and tensions set up in this earlier conversation are re-addressed and apparently resolved in one of the final conversations of the episode. The case closed, the bad guys caught, Doshi congratulates Garrett on his fine team as she walks him out of her office. She adds, reflectively:

Doshi: I understand why you think my methods diminish the science of criminal profiling.

Garrett: It’s not magic.

Doshi: No, it isn’t, but I wish you could understand that you and I are not as different as you think.In every fiber, in every print, in every drop of blood left behind, are not the dead speaking to you, Jack?

Garrett: In a manner of speaking, yes. But maybe what’s most important is that I speak for them.

This declaration is followed by a triumphant snippet of the South African national anthem, South African men praising God in SeSotho. In this exchange Gary Sinise’s Jack summarizes something of the show’s intention, namely, to allow for, to make it seem sensible that US interventionist voices should speak on behalf of other people’s histories, of other people’s suffering, for their dead.

Whether Criminal Minds, Beyond Borders knows it or not, however, this very minute there are real South Africans, not foreign actors with strange names and accents, doing what they can to speak for their own dead. South Africans who aren’t waiting for any other ‘more rational ‘outsiders to do it for them.