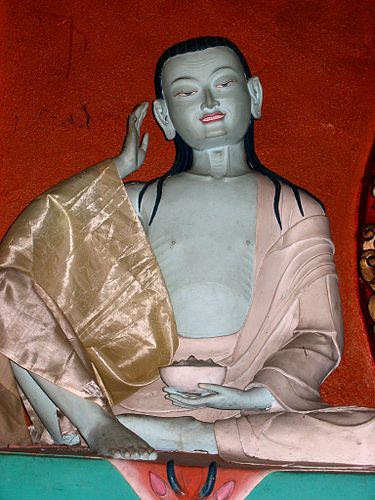

I was recently reading through Tsangnyön Heruka’s 15th century (1488 to be exact) biography of the celebrated 11th century Tibetan yogi and cultural hero Milarepa. Tsangnyön Heruka – the ‘crazy tantric yogi from Tsang’ (1452 – 1507) – reorganized and codified Milarepa’s biography from various sources, and separated this out from Milarepa’s མགུར་འབུམ་ gurbum or compendium of spiritual teaching songs. Gur is a Buddhist/tantric textual genre for which Milarepa is most famous, and refers to songs or poems which accomplished spiritual adepts are said to compose on the spot to convey in musical and poetic form key spiritual truths for audiences.

While perusing Tsangnyön Heruka’s collection of Milarepa’s songs I came across a narrative which he calls སྔགས་པའི་ཞུས་ལན་གྱི་སྐོར་ ‘Concerning Questions-and-Answers with a Ngakpa’. Readers here will probably know that my doctoral research as a cultural anthropologist was focused on Tibetan Buddhist ngakpa, or non-celibate, non-monastic tantric householders and sorcerers. I find Milarepa’s exchange with this unnamed ngakpa quite beautiful and interesting, so I thought I would share my own translation of it here. Garma C.C. Chang translated this song into English in the 60s in his ‘The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa’ (Vol. 2). I’ve reproduced his translation at the end of this post. While it has many lovely qualities, I feel that it doesn’t quite capture the thrust of some of Milarepa’s responses, which I’d like draw out more here. The gist of the short narrative is that an unnamed ngakpa from དབུས་ཕྱོགས་ Üchok, Wüchok, the region of Central Tibet, comes one day to have an audience with Milarepa. Milarepa’s yogi disciple Seban Repa asks this ngakpa what type of གྲུབ་ཐོབ་ druptop or siddhas there are where he’s from. Siddhas – literally ‘spiritually accomplished ones’, people with spiritual attainments – are yogis who have achieved various spiritual powers, ranging from mastery of psychic and healing abilities, magical powers, to meditative attainment and complete Buddhahood. Seban Repa’s opening salvo is effectively, ‘How powerful/realized are your yogis and sorcerers back home, yogi-sorcerer?’ The visiting ngakpa explains that the siddhas in his region are of such calibre that they are served or waited upon by non-human beings. It is at this point that Milarepa chimes in with a provocation:

Then a ngakpa from the region of Ü (Central Tibet) came to see the Venerable Milarepa. Seban Repa asked him: ‘What kind of siddhas are there in your region of Ü?’ ‘Our siddhas are served by non-human spirits,’ the ngakpa replied. ‘That fact alone doesn’t make someone a siddha,’ Milarepa said. Seban then asked him, ‘Do you also have this accomplishment Venerable One?’ ‘I have such accomplishment,’ he answered and sung this spiritual song:

‘Though samadhi, inexhaustible as the Treasury of Space,

Cooks my food and boils my tea,

And the Dakinis remove

All hunger and thirst and inclination for food from me,

I still do not think of myself as a siddha.’

The Shania Twain of Tantric Yoga, Milarepa explains that the ngakpa‘s talk of spirits sustaining and serving practitioners doesn’t impress him much. That power isn’t what makes a true siddha. Seban Repa’s curiosity is piqued and he then asks his Master whether he himself has such a thing. Milarepa confirms that he does, but doubles down on his point with a song. As an accomplished yogi, Milarepa can indeed sustain himself through samadhi or tingngedzin in Tibetan – deep meditative absorption, single-focused trance. The extent of his meditative absorption is inexhaustible, unconditioned, incorruptible. Unlike material food and drink, it isn’t limited, it doesn’t decay and fade away. It is thus the ultimate cook. Milarepa then confirms that of course the Dakinis or tantric goddess-helping spirits wait on him and free him from all worldly cravings and inclinations. But he still doesn’t consider himself a siddha on account of this. The ngakpa then asks Milarepa another question – he wants to know if, like other great yogic practitioners, Milarepa ‘sees the faces of the yidam or tantric meditational deities, directly’:

Hearing this the ngakpa asked him, ‘So do you also see the yidam face-to-face then?’. Milarepa answered with this song:

‘Once one has seen the nature of Mind,

And has woken up from the darkness of non-knowing,

The Dakinis reveal their faces directly.

And yet, in the expanse of the Dharmata there is nothing to be seen.

The Dakinis teach that one should

Focus one’s mind on no focus at all, on un-reifiable non-conceptuality,

That all phenomena are self-arisen and self-illumined of their own accord.

And yet, there is no teaching worth listening to other than the teaching of the Guru.

The Dakinis teach that ‘All that one could want,

The ordinary siddhis and the Supreme Siddhi of Buddhahood, and so on,

Can be accomplished in this very life’.

And yet still I do not think of myself as a siddha.’

It might help to contextualize the ngakpa‘s question a little further. In Vajrayana, as part of the so-called ‘Creation’ and ‘Completion’ – or perhaps better, ‘(Re-)birth’ and ‘Pre-death’ – stages of tantric Buddhist meditation, practitioners engage in deity yoga, in which they let go of their ordinary sense of self and re-identify with a luminous, enlightened patron meditational deity or yidam. These deities can also be visualized in a more dualistic fashion, as separate beings above or in front of the meditator, but in the Two Stages practitioners typically ‘self-generate’ as deities. Much of this involves a certain amount of contrivance, actively imagining oneself as the deity to the best of one’s ability, imagining that various deities are above or within one’s yogic body, and so on. Practitioners who have spent a lot of type visualizing and identifying with deities will eventually zhel tongwa, ‘see the face of the deity’ – that is, they will perceive the deity directly and organically in visions, see it face-to-face and receive its empowering blessings. The routine procedures of the meditative regimen or sadhana become scintillating, vivid, spontaneous and filled with energetic potency. Our ngakpa assumes that Milarepa has experienced this. Milarepa again confirms that he has, but reminds his audience – which includes you and me! – that that is not really the point. In his song, he plays poetically with terms associated with luminosity and disclosure. Yes, he tells us, the tantric goddesses or Dakinis show their faces once one has seen the ངོ་ ngo of one’s mind (ngo means ‘the essential nature’ but it can also mean ‘face’) and once the ‘obscurity’ or ‘darkness’ (མུན་པ་ munpa) of marigpa – མ་རིག་པ་ not-knowing, not-seeing, not-understanding one’s true nature, the opposite of rigpa – has been lit up or cleared away, like how the blackness of dreamless sleep is dispelled upon awakening (སངས་བ་ sangwa, which is the first syllable of the Tibetan translation for ‘Buddha’, sang-gyé, the one who cleared away obscuration and woke up to or saw Reality clearly). So yes, I’ve seen the deities’ faces, Milarepa says, but the real point is that in the expanse or wide-open space of Reality (ཆོས་ཉིད་ཀློང་ལ་ chö nyi long la, ‘within the expanse of Dharmata, the nature of things as they truly are), there is no concrete ‘thing’ that can be looked at or seen at all.

Milarepa continues, explaining that what these directly-perceived Dakinis have taught him is that paradoxically one should actively focus one’s attention (ཡིད་ལ་བྱེད་པ་ yi la ché) on no particular focus at all, one non-referentiality, on the ultimate un-reifiability of concepts, on non-conceptuality (དམིགས་པ་མེད་པ་ mikpa mepa), that if you do this, then you will realize the self or intrinsically arising nature of all concepts, thoughts, perceptions, and appearances – i.e. རང་བྱུང་ rangjung), and their ‘intrinsic’, ‘reflexive’ or ‘self-luminosity, clarity, or illumination’, རང་གསལ rangsel. These are all technical terms associated with both the Yogachara or ‘Mind Only’ Buddhist philosophical school and the Ati Yoga or Dzogchen tradition, although they are explained quite differently in each of these contexts (see Sam Van Schaik’s and David Higgen’s books on Dzogchen philosophy for more on this). Milarepa says here that what the Dakinis have conveyed is a fundamental truth about the nature of consciousness in and of itself, beyond conceptual dualism. Even so, there is no other teaching that one should listen to other than what one’s own Lama or Guru teaches, so in effect the point is moot. The engine of all Tantric Buddhism is Guru Yoga, is cultivating the ability to see Buddha-nature in one’s teacher, in directly discovering one’s own intrinsic, awakened nature through relationship with one’s teacher and other humans on the Path. Milarepa tells us that the Dakinis he’s met face-to-face say all kinds of things, that they confirm that all manner of worldly magical powers – ordinary siddhis – and Buddhahood itself can indeed be accomplished in this life, but Milarepa still doesn’t think of himself as a siddhi in the midst of this. If one cannot see that the Dakinis are one and the same with one’s own Guru, if one cannot practice Guru Yoga, then none of this really matters.

Hearing this, the ngakpa has a final question. As our stand-in for tantric sorcery, with Milarepa’s nudging, he moves gradually from asking questions about yogi or sorcerers’ extraordinary abilities, to questions about the nature of Mind itself:

The ngakpa then asked, ‘What sort of metaphors would you give to symbolize the nature of Mind?’. Milarepa sang the following song:

‘There is no metaphor at all which can represent

The non-arising or birthless-ness of Mind.

To the unrealized, all material things are metaphors for The non-ceasing or deathless-ness of Mind;

To the realized, Mind itself is the metaphor.

It cannot be divided in two, into ‘metaphor’ and ‘thing represented’.

It transcends whatever can be spoken, imagined, or expressed.

How wondrous the blessings of lineage are!’

Our ngakpa asks Milarepa for what amounts to a ‘pointing out’ instruction, an introduction to the Nature of Mind – not the ordinary mind, but Consciousness Itself, Mind-at-large. He was perhaps anticipates that Milarepa will give him some symbolic explanations, analogies, or metaphors (དཔེ་ pé), as classically occuries in the Fourth ‘Word’ empowerment of Highest Yoga Tantra, where the initiating Guru may hold up symbolic objects and give a verbal discourse on what the Nature of Consciousness is like, to try to get disciples to understand it for themselves. But Milarepa pushes back against this request. He reminds us that Mind Itself (སེམས་ཉིད་ semnyi) is non-arising or ‘birth-less’, སྐྱེ་བ་མེད་པ་ kyewa mepa: it is beginning-less, it’s not produced from anything, it doesn’t come from anywhere, it is unfabricated, uncompounded, it has no origin story. For this reason, it can’t be compared to anything which does in fact have an origin, which does come from somewhere, which was made or produced. Milarepa then reminds us that Mind Itself is also endless, death-less, non-ceasing, འགག་པ་མེད་པ་ gakpa mepa – it will never stop, deteriorate, or run out. For this reason, ‘un-realized’ – uninformed, uneducated, unaware, foolish people, མ་རྟོགས་པ་ matokpa compare everything thing to Mind, they make analogies with all material things or phenomena – that is, because they’re stupid enough to think that all material phenomena are also ‘endless’, that phenomena are permanent. Those who really do understand the nature of Mind, however, realize that Mind Itself is its own metaphor. By its very nature it is beyond any sort of conceptual splitting into ‘symbol’ and ‘symbolized’, ‘representation’ and ‘reality’ (དཔེ་དོན་གཉིས་ pé dön nyi). The nature of Mind is wholly ineffable and inconceivable – it is beyond all objectivification or reification via speaking, thinking or imagining, expressing or communicating.

Milarepa ends his apophatic pointing out with a powerful conclusion, which may seem a bit like a non-sequitur at first sight. ‘How wondrous the blessings of lineage are!’ he proclaims. ངོ་མཚར་ཆེ་ ngotsar ché means ‘very miraculous, amazing, wonderful, strange, extraordinary, wondrous’. I chose to use ‘wondrous’ in my translation to capture the idea that the blessings are great, inspiring, awesome, but that they are also something miraculous. Why are these jinlap or empowering-blessings so amazing? Because despite the fact that the Nature of Mind is beyond anyone’s capacity to explain, represent, or convey, when a suitably prepared and qualified student meets or aligns with a suitably prepared and qualified Guru or teacher, in whatever form, a kind of chemical reaction can in fact take place which transforms the student and lights them up to their own nature. The Tibetan for ‘blessings of the lineage’ is བརྒྱུད་པའི་བྱིན་རླབས་ gyüpé jinlap. The word gyüpa means ‘lineage’ in the sense of a line of spiritual transmission. We can think of it as a ‘continuum’ of transmission as well. In the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism in particular, there is a teaching about the བརྒྱུད་གསུམ་ gyü sum, ‘The Three Lineages’ or maybe better, ‘The Three Transmission-Continuums’. The first of these is རྒྱལ་བ་དགོངས་པའི་བརྒྱུད་པ་ gyalwa gongpé gyüpa, ‘The Enlightened Mind Transmission-continuum of the Buddhas’, the second is རིག་འཛིན་བརྡའ་ཡི་བརྒྱུད་པ་ rigdzin da yi gyüpa, ‘The Symbolic Transmission-continuum of the Vidyadharas’ and the third is the གང་ཟག་སྙན་ཁུང་གི་བརྒྱུད་པ་ gangzak nyenkhung gi gyüpa, ‘The Heard ‘Ear-Hole’ Transmission-continuum of Human Teachers’. These transmission-continuums correlate to the Dharmakaya, Sambhogakaya, and Nirmanakaya. When Milarepa speaks about how amazing the blessings which stream potently and uninterrupted via the lineages or transmission-continuums are, he is again pointing, if obliquely, to the question of symbols, of representations and stand-ins versus Reality and the Thing Itself.

Why do I say this? Simply put, because human Gurus themselves are a symbol which refer back to the inexpressible, non-referential nature of Mind. The following is a brief summary of teachings on the various levels of Guru in Vajrayana, which was recorded by Sumtön Yeshe Zung in the late 12th century, early 13th century, after receiving them from Yuthok Yönten Gönpo, his root Guru:

“In general, all of the Kama teachings (i.e. teachings spoken by the Buddhas), all sutras, tantras and upadesha texts of pith instruction are in agreement that all happiness in Samsara-Nirvana depends on the Guru, that attaining Buddhahood in a single human lifetime too depends solely on one’s reverence or devotion to the Guru, and that without relying on the profound path of devotion, Buddhahood cannot arise. [But understand that] the Guru can be divided into two categories:

1) Nangwa Dé Lama, the ‘symbolic appearance’ or ‘external’ Guru and

2) Rangsem Ngö ki Lama, the Guru who is the actuality, the actual nature of one’s own mind’, the ‘inner Guru’.

There are four types of symbolic appearance Gurus:1. The Tsawé Lama or Root Guru

2. The Gyüpé Lama or Lineage Guru

3. The Deshek Ka yi Lama, the Guru of the Instructions of the Sugatas

4. The Kunkhyab Rangjung gi Lama, the All-pervasive, naturally-occurring Guru

The first symbolic appearance Guru is whoever introduces you to the very nature of your own mind as Buddha, whichever person points out that the nature of your own mind is itself Buddha.

The second includes all lineage-lamas from this root-lama all the way to Vajradhara (i.e. the original, primordial tantric Buddha or archetypal Guru).

The third is all the texts of the Kama, the Sutras, and Tantras, all the agamas and upadesha pith instructions. Here the Guru takes on the form of collections and volumes of scriptures and works on behalf of beings. This symbolic appearance Guru is known as ‘the black loppön – the acharya or learned master – who is free from anger’ (i.e. because Tibetan religious texts darken with regular use from ink smudging and so on, and books sitting calmly on shelves do not lose their patience with students like human teachers!).

The fourth symbolic appearance Guru is all forms and other arisings emerging within the domain of sensory experience. For example, when one looks at the essence or true nature of all apparent forms, one is introduced, through the medium of symbol or representation, to the fact that, as it is said, “they are nothing but appearances” and to the fact that their “appearance as forms and their fundamental emptiness is indivisible”. All the other senses – smells, sounds, and so on, follow this same pattern.

The second type of Guru, the so-called ‘Guru that is the actual nature of one’s own mind’ differs from the aforementioned types of Gurus. This Guru amounts to nothing other than the natural potentiality or expression of one’s own Mind – there is not even the slightest atom’s worth of distinction between the two. Look at the essence or true face of your mind, whether it be at rest or in motion. Look yourself at its very essence, without becoming distracted or trying to ‘meditate’, to cultivate anything, planting the sentry of mindfulness, of remembering, each second. When you liberate all the appearances of apprehender and apprehended, of attachment and aversion, in their own ground, you will directly realize the teaching about the underlying ultimate nature of Reality.

Thus, your own Mind – the King of all Gurus, the loppön, the master who is revealed from out of the underlying reality of all phenomena – is timeless, is beyond the parameters of past, present, and future, has never known the coming together and breaking apart that typifies all phenomena. In this way, understand that it is not apart or separate from you, that it is beyond the suffering of samsara, beyond action and free from an actor. For this reason, not even a single atom from the total extent of conceivable phenomena and appearances, from ‘the level of form to that of total omniscience’, is not the Guru. When any conception of good or bad, right or wrong, of rejecting or taking up arises in relation to this Guru that is your own Mind, which is all the Buddhas of past, present, and future then, that is grasping onto self and onto things as concrete or substantial. It is taught that this is no other than the seed from which conditioned existence, from which samsara unfolds…”

Thus, we can see that the ‘miracle’ Milarepa ends his song with, is the fact that outer symbols, external, compounded, born-and-dying Gurus, can empower us in such a way as to facilitate the realization of what is beyond all duality, beyond birth and death., of what is deep within as our own, innate, unseen nature.

After hearing this final song, the visiting ngakpa has his own aha! moment. The very thing Milarepa sings about becomes exemplified and instantiated in his own reaction, with the sudden ripening of his own understanding:

Hearing this, the ngakpa’s karmic imprints from previous lives were awakened. He developed unshakable devotion towards Milarepa and became his follower and attendant. Milarepa gave him empowerments and oral instructions and he put these into practice meditatively. Through this he became a very distinguished tokden, or realized yogi.

This completes the short narrative. In sum, Milarepa shows us that the magic or accomplishments of a true Siddha have nothing to do with special powers. The true Siddha’s accomplishment comes from listening to the teachings of their Guru and lineage and applying them to realize Mahamudra, the Nature of Mind, which is called the ‘Great Symbol, Sign, or Gesture’, and which is no symbol or metaphor at all.

Truly, how wondrous the blessings of lineage are!

Here is the original Tibetan for the above narrative, followed by Garma C.C. Chang’s earlier translation (pp. 660 – 661 in Vol. 2 of the 1977 Shambhala edition), for comparison. You can read the entirety of Tsangnyön Heruka’s Tibetan text here for free.

དེ་ནས་རྗེ་བཙུན་གྱི་དྲུང་དུ་དབུས་ཕྱོགས་ཀྱི་སྔགས་པ་ཞིག་མཇལ་དུ་བྱུང་བས། དེ་ལ་སེ་བན་རས་པ་ན་རེ། ཁྱོད་ཀྱི་དབུས་ཕྱོགས་ན་གྲུབ་ཐོབ་ཅི་འདྲ་ཡོད་ཟེར་བས། མི་མ་ཡིན་གྱིས་ཞབས་ཏོག་བྱེད་པ་ཡོད་ཟེར་བས། རྗེ་བཙུན་གྱི་ཞལ་ནས། དེ་རང་གིས་གྲུབ་ཐོབ་ཏུ་མི་འགྲོ་གསུང་བ་ལ། སེ་བན་ན་རེ། རྗེ་བཙུན་ལ་ཡང་ཡོད་ལགས་སམ་ཞུས་པས། ང་ལ་འདི་འདྲ་ཡོད་གསུངས་ནས་མགུར་འདི་གསུངས་སོ། མི་ཟད་ནམ་མཁའི་མཛོད་ལྟ་བུ། ། ཏིང་ངེ་འཛིན་གྱི་གཡོས་སྐོལ་གྱིས། ། བཀྲེས་སྐོམ་ཟས་ཀྱི་འདུན་པ་དང་། ། བྲལ་བར་མཁའ་འགྲོ་མ་རྣམས་བྱེད། ། དེ་ཡང་གྲུབ་ཐོབ་ཡིན་སྙམ་མེད། ། ཅེས་གསུངས་པས་སྔགས་པ་ན་རེ། ཡི་དམ་གྱི་ཞལ་མཐོང་བ་ཡང་ཡོད་ལགས་སམ་ཞུས་པས་མགུར་འདི་གསུངས་སོ། ། སེམས་ཀྱི་ངོ་བོ་མཐོང་གྱུར་ཅིང་། ། མ་རིག་མུན་པ་སངས་པས་ན། ། ཞལ་དག་མཁའ་འགྲོ་མས་ཀྱང་སྟོན། ། ཆོས་ཉིད་ཀློང་ལ་ལྟ་རྒྱུ་མེད། ། དམིགས་མེད་ཡིད་ལ་བྱེད་ཅིང་། ། རང་ཉིད་རང་བྱུང་རང་གསལ་གྱི། ། ཆོས་རྣམས་མཁའ་འགྲོ་མ་ཡིས་གསུང་། ། བླ་མའི་གསུང་ལས་གཉན་པ་མེད། ། མཆོག་དང་ཐུན་མོང་ལ་སོགས་པའི། ། དགོས་པ་ཐམས་ཅད་ཚེ་འདི་རུ། ། འགྲུབ་ཅེས་མཁའ་འགྲོ་མས་ཀྱང་གསུང་། ། དེ་ཡང་གྲུབ་ཐོབ་ཡིན་སྙམ་མེད། ། ཅེས་གསུངས་པས། ཁོ་ན་རེ། སེམས་དཔེ་ཇི་ལྟ་བུ་ཞིག་གིས་མཚོན་པ་ལགས་ཞུས་པས་མགུར་འདི་གསུངས་སོ། ། སེམས་ཉིད་སྐྱེ་བ་མེད་པ་འདི། ། དཔེ་ནི་གང་གིས་མཚོན་དུ་མེད། ། སེམས་ཉིད་འགག་པ་མེད་པ་འདི། ། མ་རྟོགས་པ་ལ་དངོས་ཀུན་དཔེ། ། རྟོགས་པ་རྣམས་ལ་སེམས་ཉིད་དཔེ། ། དཔེ་དོན་གཉིས་སུ་མ་ཕྱེད་ཅིང་། ། སྨྲ་བསམ་བརྗོད་པའི་ཡུལ་ལས་འདས། ། བརྒྱུད་པའི་བྱིན་རླབས་ངོ་མཚར་ཆེ། ། ཞེས་གསུངས་པས། ཁོ་བག་ཆགས་སད་པས། རྗེ་བཙུན་ལ་མི་ཕྱེད་པའི་དད་པ་ཐོབ་ནས་ཕྱག་ཕྱིར་འབྲངས་པ་ལ། དབང་དང་གདམས་ངག་གནང་ནས་བསྒོམས་པས་རྟོགས་ལྡན་ཁྱད་པར་ཅན་ཞིག་བྱུང་ངོ་། །