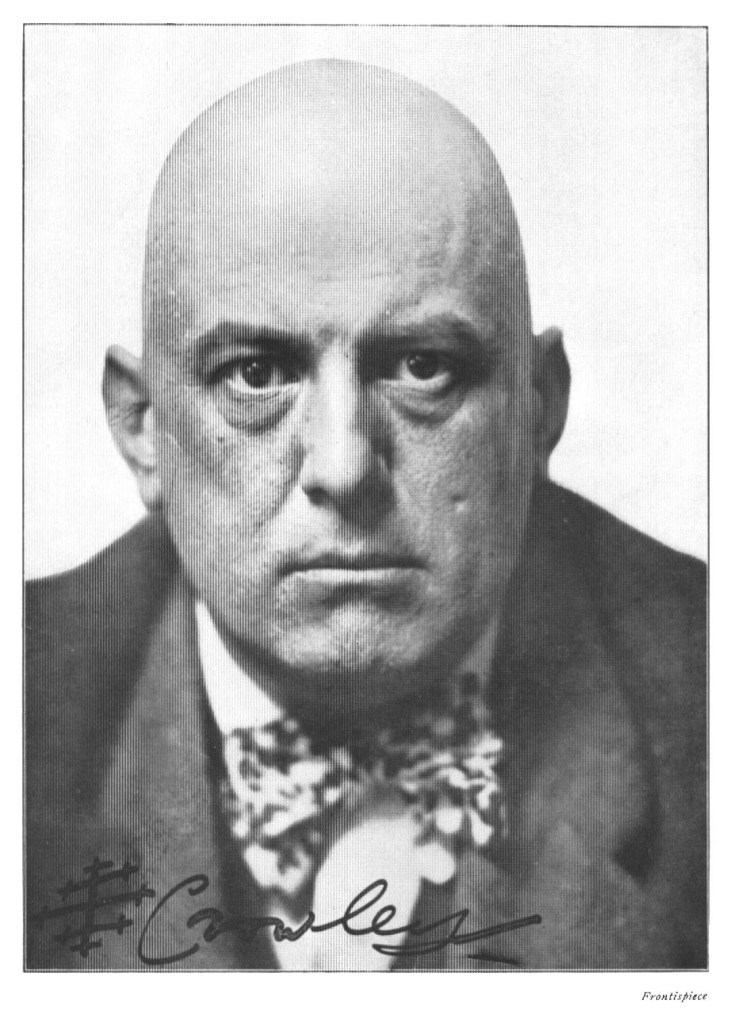

I’ve written about LAM, the according-to-some extraterrestrial entity which English ritual magician Aleister Crowley is supposed to have contacted, in an earlier article about ‘Tibetan aliens’ which I shared on this blog before. The term LAM is synonymous with a specific drawing which Crowley produced, and which some occultists say is a portrait of a specific spiritual/alien entity. Now, occultists have many different opinions about who or what LAM is or was, about whether this picture is even a picture of an entity at all, and about the extent to which whatever entity or spiritual principle the image may represent is important or interesting. Some claim the image of LAM is Crowley’s spiritual self-portrait, others that it is a picture of Crowley’s Guru or Holy Guardian Angel. Some say it a portrait of Lao Tzu or another Taoist sage, of a disincarnate Tibetan lama, or the likeness of some other sort of priest or sorcerer. Others argue it is a stylized representation of penis-in-vagina (ritual?) intercourse, while yet others claim that it is one of the earliest representations of the now stereotypical ‘grey alien’ extraterrestrial (this last position seems to have gone especially viral online in the late 90s and 2000s).

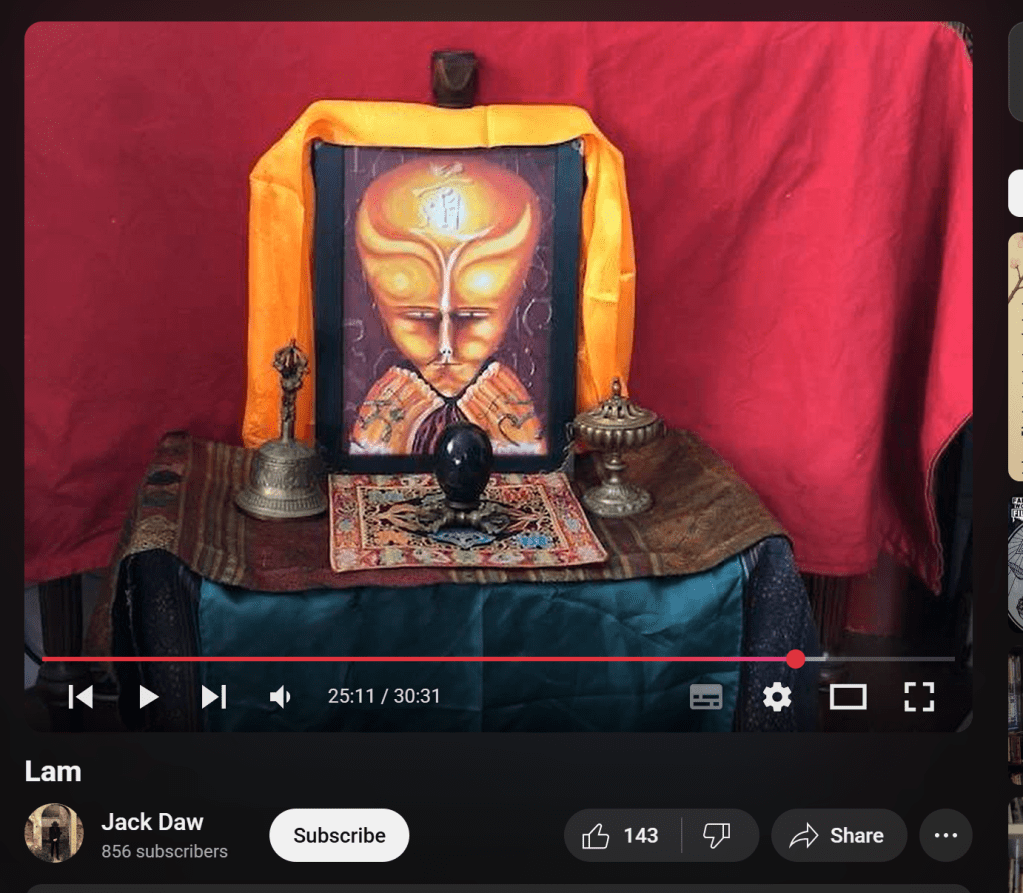

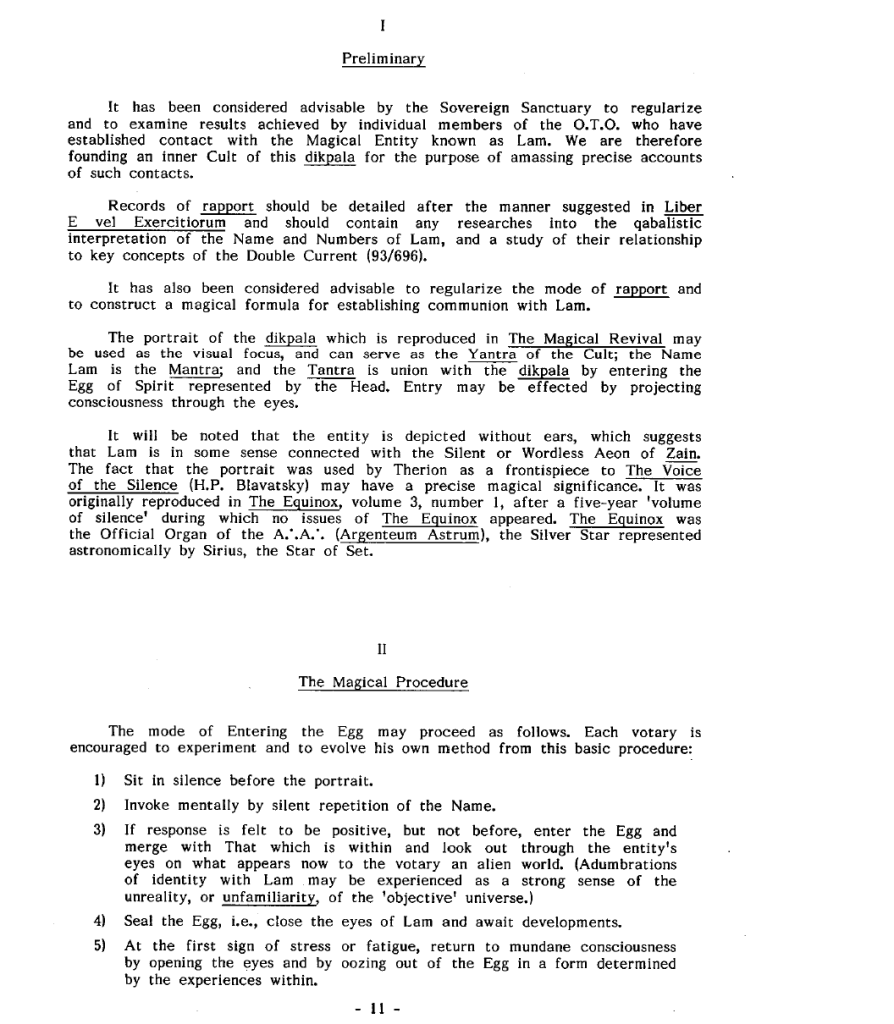

Crowley included the drawing in his ‘Dead Souls’ exhibition held in Greenwich, New York, in 1919 and then published it as a frontispiece in his commentary on Helena Blavatsky’s pseudo-Buddhist (Buddhist fanfic?) Theosophical treatise The Voice of the Silence in the same year. Much later, Crowley gifted the portrait to his personal secretary, occultist Kenneth Grant and Grant subsequently developed a ‘Cult of LAM’ – cult in the more classical sense of cultus. This Cult advocated for a set of experimental ritual-contemplative practices based on the idea that Crowley’s picture does in fact represent a ‘trans-Plutonian’ extraterrestrial being or spiritual principle. Grant (in)famously linked Crowley’s new religion of Thelema with the alien deities of H.P. Lovecraft’s fiction, developments in UFOlogy, and various religious and literary traditions which Crowley had previously paid little to no attention to. Grant and fellow investigators of his proposed ‘Typhonian current’ of spiritual gnosis, articulated their own understanding of Crowley’s picture and its importance, based on their personal experiments with using the artwork as a kind of meditative or mediumistic focus. Grant explained his own understanding of Crowley’s image in a document from the tail end of the 1980s titled ‘The Lam Statement: Concerning the Cult of Lam, the Dikpala of the Way of Silence’ (dikpala is a Sanskrit word for ‘directional guardian’, a term used to describe deities which protect and govern the various directions in Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist cosmologies). At the risk of overwhelming the casual reader with Western occult jargon right at the outset, here’s Grant’s statement in full:

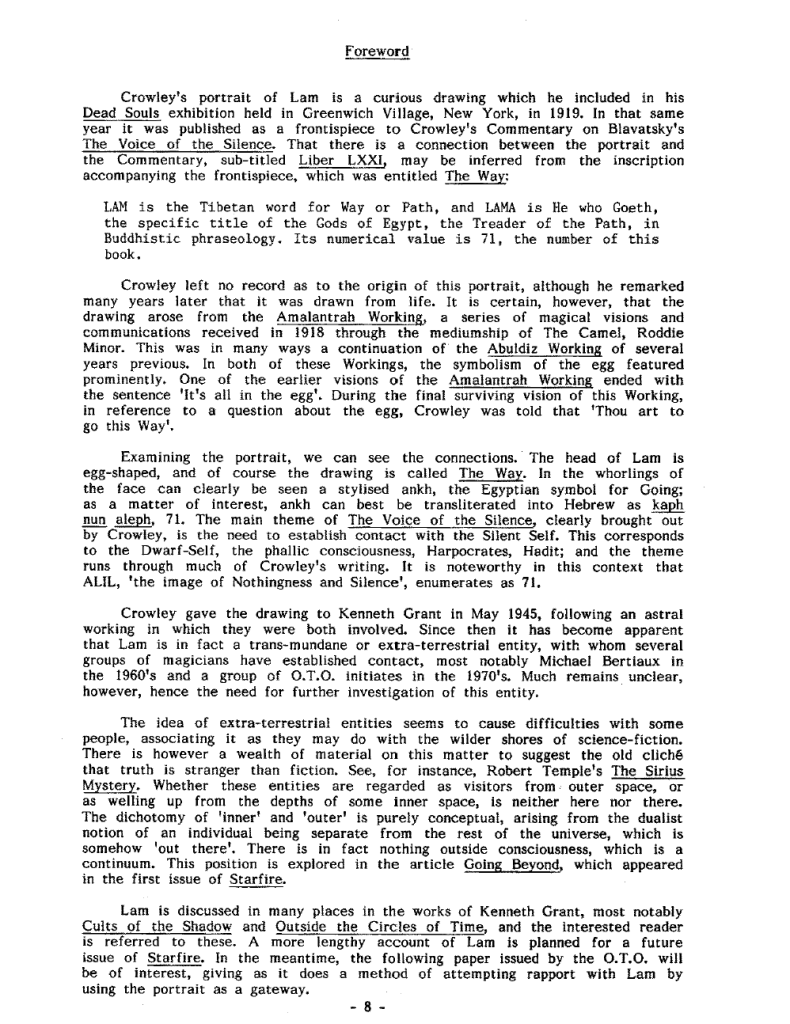

In publications and conversations following Crowley’s death, Grant claimed that Crowley confirmed to him that the LAM portrait was a picture of his (i.e. Crowley’s) own spiritual guru, an image ‘drawn from life’, an expression of Aiwass, Crowley’s Holy Guardian Angel. At the same time, it is important to note that Crowley never actually said anything directly himself on record about the image and its origin or subject, beyond the caption he included under the picture when he published it as a frontispiece to his commentary on Blavatsky’s work in 1919. Grant explains that Crowley challenged him to tell him who or what he thought the portrait’s subject was. Despite apparently not answering to Crowley’s satisfaction, Crowley still let Grant have the drawing and the rest is New Religious Movement history. Because of when the portrait appears to have emerged, i.e. around 1918, 1919, it is often linked to the Amalantrah Working, a series of rituals or seances which Crowley conducted in New York in 1918 with the help of Soror Ahita – the American pharmacist otherwise known as Roddie Minor. Minor served as a the primary medium for communications during this Working with the eponymous ‘wizard’ Amalantrah, a disembodied sage who conveyed a variety of esoteric messages and teachings as well as mundane instructions and advice to Crowley and Minor via visions over the course of about six months. Images of eggs and themes of childbirth featured prominently in these extensive transmissions and adherents of Grant’s ET interpretation of the image have made much of LAM’s alien egg-headed-ness in this regard (Crowley left us only a fairly incomplete record of the Amalantrah seances, which can be read here).

“It is necessary to say here that The Beast appears to be a definite individual; to wit, the man Aleister Crowley. But the Scarlet Woman is an officer replaceable as need arises. Thus to this present date of writing, Anno XVI, Sun in Sagittarius, there have been several holders of the title. … 4. Roddie Minor. Brought me in touch with Amalantrah. Failed from indifference to the Work.”—New Comment, I 15, see also Amalantrah

“Early in October, I broke up the menage and transferred my headquarters to a studio in West 9th Street, which I shared with a friend of the Dog’s, hereafter described as the Camel.

Her name was Roddie Minor, a married woman living apart from her husband, a near artist of German extraction. She was physically a magnificent animal, with a man’s brain well stocked with general knowledge and a special comprehension of chemistry and pharmacy. She was at this time employed in the pathological laboratory of a famous doctor, but afterwards became managing chemist to a prominent firm of perfumery manufactures.

I have said that she had a man’s brain, but despite every effort, there was still one dark corner in which her femininity had taken refuge and defied her to expel it. From time to time the garrison made a desperate sortie. At such moments her womanhood avenged itself savagely on her ambition. She was more frantically feminine than any avowed woman could possibly be. She was ruthlessly irrational. Such attacks were fortunately as short as they were severe, but unfortunately too often did irreparable damage.

In the upshot, this characteristic led to our separation. I treated her as an {781} equal in all respects, and for some months everything went as smoothly as if she had been really a man. But that beleaguered section of her brain sent out spies under cover of night, and whispered to the besiegers sinister suggestions, to shake their confidence in themselves. The idea was born and grew that she was essentially my inferior. She began to feel my personality as an obsession. She began to dread being dominated, though perfectly well aware that I wished nothing less, that her freedom was necessary to my enjoyment of my own. But she failed to rid herself of this hallucination, and when I decided to make a Great Magical Retirement on the Hudson, in a canoe, in the summer of 1918, we agreed to part. There was no quarrel. Our friendship and even our intimacy continued. My last night in New York before leaving for Europe was spent in here arms.”

Kenneth Grant’s student Michael Staley, who wrote the foreword to the 1987 Lam Statement, explains there his and Grant’s belief that Crowley’s image was somehow connected to the wizard Amalantrah and his Working:

In my older Savage Minds article, I reflected on how the Crowley image and Grant’s interpretation sums up Western occultists’ ideas about Tibet, Buddhism, and aliens in interesting ways and mused about what so-called ‘Tibetan aliens’ can teach us about religious innovation and syncretism. In this blog post though, I’d like to address an aspect of the LAM portrait which I didn’t much get into in my earlier piece, i.e. LAM’s name, and the way that Crowley connects it to the Tibetan word lama in his frontispiece.

As we see in the Lam Statement, Crowley captioned his 1919 frontispiece as follows:

“THE WAY

LAM is the Tibetan word for Way or Path, and LAMA is He who Goeth, the specific title of the Gods of Egypt, the Treader of the Path, in Buddhistic phraseology. Its numerical is 71, the number of this book.“

Here Crowley takes us on a typical Western occult rollercoaster ride of creative correlation and syncretism. He titles his image THE WAY, reminiscent of English translations of the Chinese term Tao/Dao, and then explains that LAM is the Tibetan word for Way or Path. Here’s where Crowley is in fact on the money. The Tibetan word lam – ལམ – does indeed mean way, path, or road. Crowley then goes on to link the Tibetan word lam to another Tibetan term, lama. Lama is both a title and a general Tibetan term meaning a guru, a spiritual teacher, initiator, or guide, especially one who grants Tantric Buddhist transmissions of various kinds. In his caption, Crowley implies that the word lama is etymologically connected to or derived from the word lam, and explains that lama is to be glossed as ‘He who Goeth’, a term which he tells us is also a title for Ancient Egyptian deities. He goes on to add that ‘Treader of the Path’ would be the more ‘Buddhistic phraseology’ for expressing this same concept. Simply put, Crowley argues that a lama is someone who ‘lam’-s, who travels on a lam or spiritual path.

This is confidently argued on Crowley’s part, but unfortunately incorrect. The Tibetan word lama བླ་མ bla ma – which is the standard Tibetan translation for the Sanskrit word ‘guru’ – is not etymologically linked to the Tibetan word lam ལམ ‘way, path, road’, even though they do sound similar when pronounced (more on the actual etymology of the Tibetan word lama below). It’s fairly easy to see how Crowley could have made this assumption, since lam and lama are only one letter away in phonetic English transliteration. It’s harder to understand though, if you’re not already familiar with twentieth century Western occultism, why Crowley saw fit to connect Daoism and Ancient Egyptian gods to Tibetan lamas and Buddhism in the first place. Something like an answer to that particular question is nestled in the final portion of Crowley’s caption, in which he notes that the ‘numerical value’ of LAM is 71, which in turn ‘is the number of this book’.

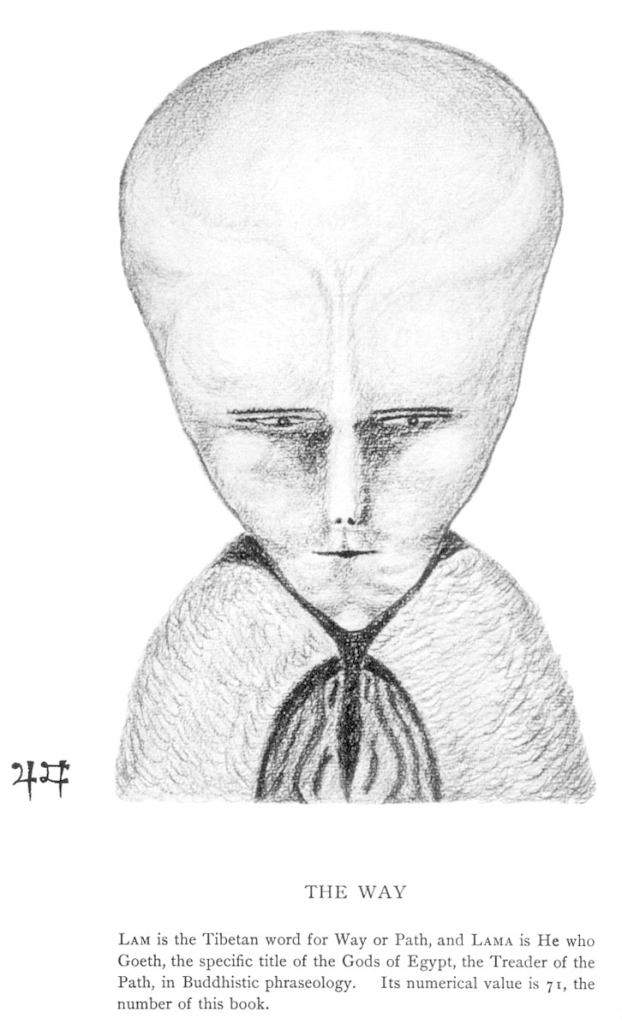

Here, Crowley is referring to the practice of Gematria, a type of Hebrew numerology used in Jewish and not-so-Jewish Qabalistic traditions. Letters of the Hebrew alphabet have numeric as well as phonemic values. As such, any Hebrew word or any word transliterated into Hebrew letters can be transformed into a number, by adding together the numerical values of its individual letters. Words which add up to the same number or which have a numerical relationship to one another are said to be esoterically linked and gematria is the practice of revealing and exploiting these numerical affinities to articulate esoteric truths. In twentieth century Western occultism, gematria became a popular tool for finding and substantiating not immediately obvious connections between concepts, words, deities, and practices from otherwise disconnected contexts and traditions. Tibetan lamas might not think that their spiritual traditions have anything to do with Jewish mysticism, Ancient Egypt, Taoism, or aliens, but gematria functions as a kind of esoteric proof regardless – as a way of arguing for a secret, primordial, unifying truth behind seemingly disparate phenomena or spiritual practices. Similarities between the sounds or spellings and transliterations of words in different languages is another kind of correlation, which is regularly relied upon by occult and alternative history exegetes as well.

The numerical values of the Hebrew alphabet. There’s a running joke in occult circles that you’re not a real occultist until you’ve managed to get your name to add up to 666 through convoluted gematric gymnastics. My first and last names are already Hebrew – בן יופי, which adds up to 158. Some phrases from the Torah with this same value are ‘In the morning’, ‘for camels’, ‘in the middle’, ‘for war’, ‘in the end’ ‘the summit’ and also ‘boiling water’ and ‘Passover’. I dunno about you, but I think the implications of that are well, pretty damning and obvious. Image taken, slightly improbably, from a UK landscaper’s website.

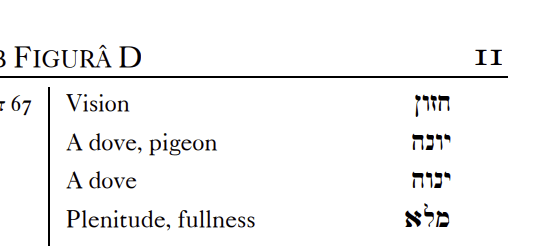

From what I can gather, Crowley seems to have taken the English word LAM and the three English letters L A M and to have transliterated these into Hebrew to come up with the sum of 71, i.e.:

L, Lamed = 30

A, Alef = 1

M, Mem = 40

LAM = 71

Here are some Hebrew words that add up to 71 as found in Crowley’s Sepher Sephiroth or Liber 777, a kind of gematric dictionary which Crowley first published in 1909.

You can see that Michael Staley draws on some of these listings in his foreword to the LAM statement, when he notes that 71 is also the gematric number for the word אֱלִ֑יל (pronounced elil). Staley glosses this words as ‘Image of Nothingness and Silence’, following Grant’s lead, who in his publications seems to fuse together the Hebrew term elil with ilem אלם, ‘silent’, another 71 term. In the Hebrew Bible, elil is commonly used to refer to an ‘idol’ or ‘graven image’ and is etymologically linked with words in Semitic languages meaning ‘worthless’ and ‘weak’. In the Tanakhic context, elil is a term of denigration, implying a weak, limited, and useless god, a false idol which cannot speak truth and is easily crushed or toppled. Grant, however, takes the nothing-ness and muteness implicit in the Biblical terms and recasts these in a more favorable, mystical light, in a way that suggests a mask or icon which points towards silent or ineffable spiritual Truth. In his foreword Staley provides another more positive gematric connection as well: he takes ankh, the most common English transliteration of the Ancient Egyptian term Ꜥnḫ, the so-called ‘key of life’ and transliterates this English transliteration into Hebrew – because, I mean, why not – to get Alef, Nun, Kaf, which also adds up to 71 (for what it’s worth, ankh is mostly written Ayin Nun Cheth in modern Hebrew, which gives a gematric sum of 128). In any case, by now it should be clear that gematria is a choose-your-own-adventure kind of exercise in modern occultism. The point is to find and prove connections to see what avenues of thought, inspiration, and experience are opened up in this process. Paying proper homage to the lesser gods or idols of linguistics, history, religious studies, and so on, is less important.

It is telling (I think?) that Crowley chose to transliterate the three English letters L A M into Hebrew for his gematric investigations. Crowley clearly understood – or knew someone who understood – that the Tibetan word lam was written with only two Tibetan letters L and M. We know this because Crowley included a rendering of the word lam in Tibetan to the left side of his drawing, albeit without the required Tibetan syllable punctuation marks. Voilà:

ལམ

Crowley didn’t know much about Tibetan and Himalayan Buddhism or at least, he probably didn’t know that much more about it than Blavatsky did, although he did most probably engage with Tibetan Buddhist and Tibetan dialect speaking porters during his mountaineering activities around the Indian-Nepal border. Crowley couldn’t read, write, or speak Tibetan fluently, but he did know enough Tibetan to write LAM correctly or to have someone else do it. His Tibetan M is boxier than necessary and closer to a Sanskrit Devanagari one, but the Tibetan L is unmistakable and cannot be confused with a Devanagari one. Any reader and writer of Tibetan can immediately identify Crowley’s glyphs as Tibetan letters and since Crowley specifically talks about the Tibetan word lam, ‘The Way’, in his caption, there is really little reason to believe the glyph could represent anything else. Correctly writing a Tibetan word as an Englishman who didn’t know Tibetan in 1919 wasn’t necessarily a very easy thing to do, but it wasn’t an impossible thing to accomplish either. British political officer Sir Charles Bell published the first edition of his accessible grammar of colloquial Tibetan in 1905 and Bengali Tibetologist Sarat Chandra Dash published the first edition of his Tibetan to English dictionary in 1902. It is not unthinkable that Crowley would have had access to these texts. Crowley was part of the expedition which attempted to summit Kangchenjunga/Gangchen Dzönga གངས་ཆེན་མཛོད་ལྔ, the third-highest mountain in the world which straddles the India/Nepal borderlands, in 1905.

As with Hebrew, the Tibetan alphabet consists of various consonants. Vowels are indicated by adding different vowel marks above and below these consonants, rather than by using separate standalone letters. When the root letter of a Tibetan syllable has no explicit vowel marks added, the inherent vowel sound of the syllable is an ‘a’ sound. All Tibetan consonants have an inherent ‘a’ sound unless otherwise marked. The ‘a’ sound in the word lam is thus implicit in the first letter, L ལ. Crowley clearly understood that the word lam only had two letters in Tibetan and that vowels were not separate letters in either Tibetan or Hebrew, yet he opted to render ལམ in Hebrew as the more anglicized לאם Lamed Alef Mem, LAM, rather than the arguably more intuitive לם . Adding in the A or alef makes the gematria 71 rather than 70, so we can maybe assume that 71 aligned better with the mystical exegesis Crowley was going for than 70.

Whatever the case though, one thing that is very clear is that Crowley’s writing of the Tibetan word lam in actual Tibetan letters beside his drawing has been routinely missed or misinterpreted by occultists – to the extent that ‘misinterpretation’ is a problem or is not the point of the exercise in this corner of the multiverse, anyway. I’ve seen occultists misconstrue Crowley’s Tibetan L ལ as the astrological glyph for the planet Jupiter, for example:

…or assume that the letters are Sanskrit rather than Tibetan (understandable, given the fact that the Tibetan alphabet was based on the Gupta script, the same script on which Devanagari was based). A number of commentators have also claimed that the letters aren’t letters at all, but are actually the number 49 written in an ‘Oriental’ seeming font.

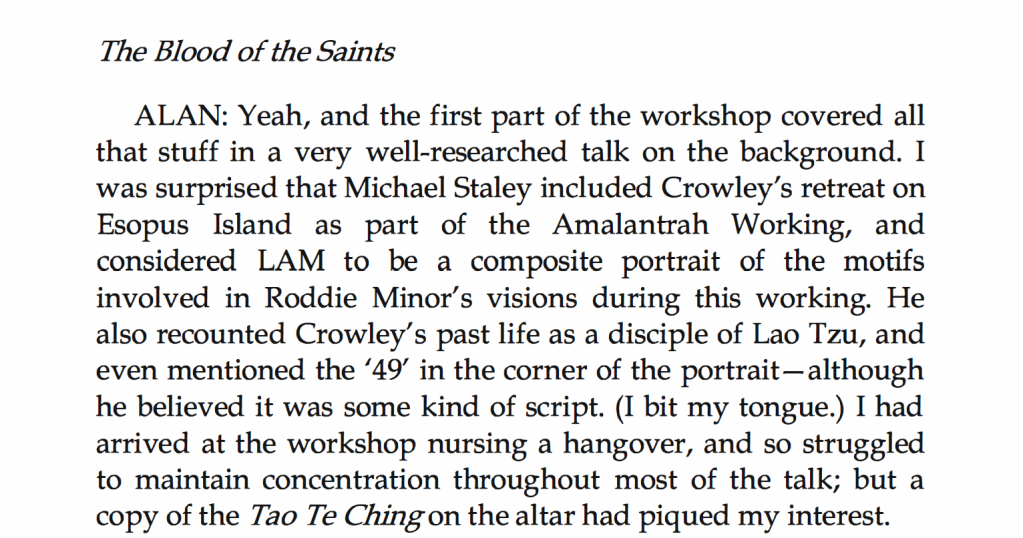

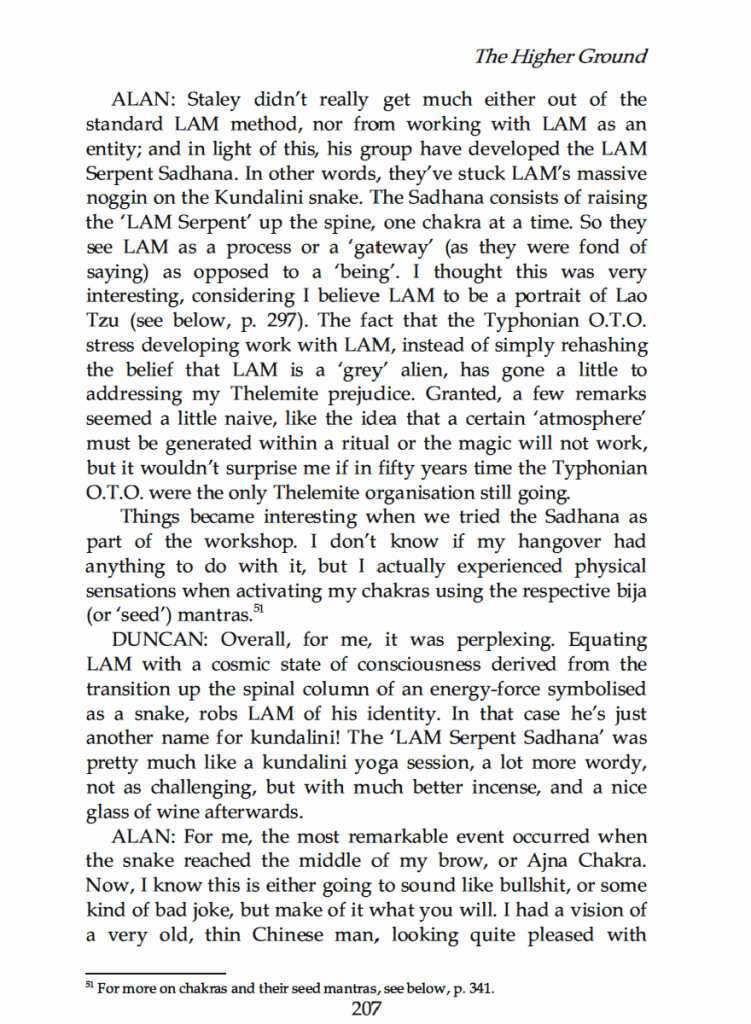

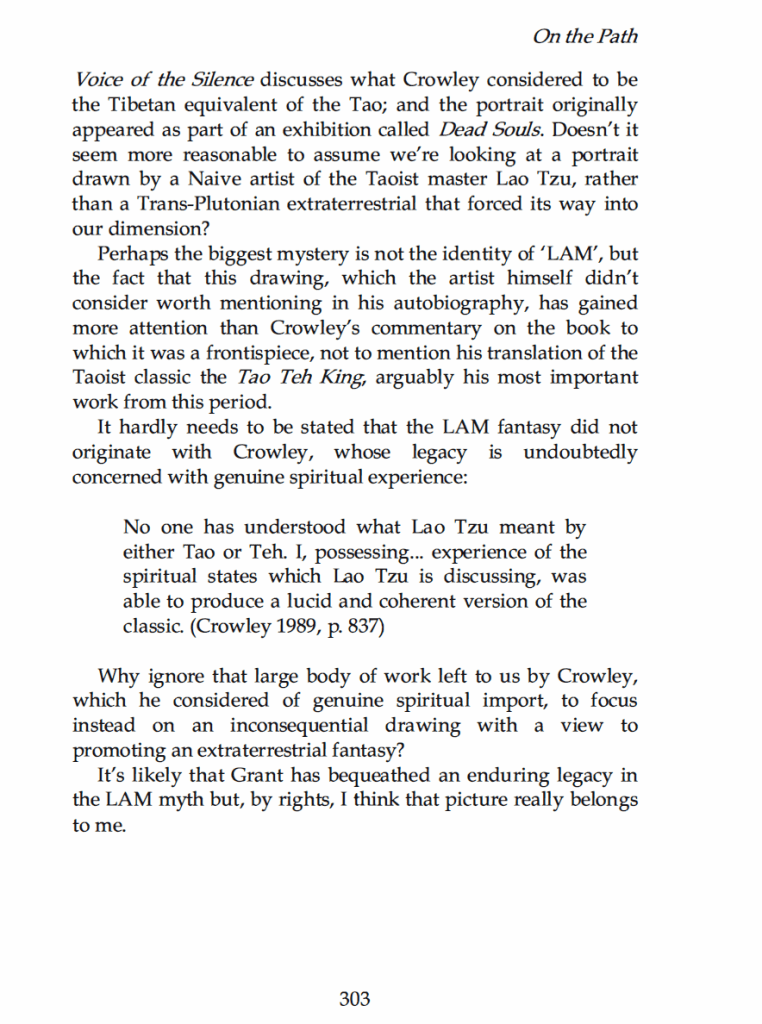

Occultists Alan Chapman and Duncan Barford are prominent proponents of this interpretation. In their 2009 book Blood of the Saints, they make much of this point. Chapman seems positively convinced that identifying these glyphs as the number 49 is the key to solving everything about the portrait and its true meaning to Crowley. In brief, Chapman and Barford, elaborating on Staley’s own comments, argue that the LAM portrait is best understood as a representation of the Daoist master Lao Tzu, who Crowley communed with following the Alamantrah Working, during a solitary retreat he undertook on Esopus Island in the Hudson River. Here is an excerpt of a dialogue between Chapman and Barford shared in their 2009 book, where the two magicians discuss attending a workshop on LAM-related practices with Staley in 2007. Chapman’s aside, ‘I bit my tongue’, conveys the extent to which he felt or feels that identifying the glyphs in Crowley’s drawing as Tibetan or any other type of letters is incorrect:

The conversation goes on, and the longtime friends and magical collaborators share more about their own experiences with and theories about LAM. Later in the text, Chapman reprints an older essay (‘Chinese Whispers: The Origin of LAM’, originally published in the Fortean Times under the name ‘Who Let the Greys In?’) where he argues his case that LAM is not an extraterrestrial but is in fact a representation of Lao Tzu or a kind of synthesis of Crowley’s experiences during the Alamantrah Working which then led to his shattering mystical insights on Esopus Island as part of his work plumbing the mysteries of the Taoist/Daoist classic the Tao Te Ching/Dao De Jing. Crowley produced his own ‘translation’ of the text, despite not knowing how to read it in its original language, claiming that his direct mystical experiences allowed him to articulate its deeper meaning better than any mere scholar of ancient Chinese could. In his Introduction to this new ‘translation’, Crowley specifically clarifies that the wizard he contacted during the Alamantrah seances assisted him to decode the Chinese text:

“From 1908 to 1918, the Tao Teh King was my continual study. I constantly recommended it to my friends as the supreme masterpiece of initiated wisdom, and I was as constantly disappointed when they declared that it did not impress them, especially as my preliminary descriptions of the book had aroused their keenest interest. I thus came to see that the fault lay with Legge’s translation, and I felt myself impelled to undertake the {12} task of presenting Lao Tze in language informed by the sympathetic understanding which initiation and spiritual experience had conferred on me. During my Great Magical Retirement on Aesopus Island in the Hudson River during the summer of 1918, I set myself to this work, but I discovered immediately that I was totally incompetent. I therefore appealed to an Adept named Amalantrah, with whom I was at that time in almost daily communion. He came readily to my aid and exhibited to me a codex of the original, which conveyed to me with absolute certitude the exact significance of the text. I was able to divine without hesitation or doubt the precise manner in which Legge had been deceived. He had translated the Chinese with singular fidelity, yet in almost every verse the interpretation was altogether misleading. There was no need to refer to the text from the point of view of scholarship. I had merely to paraphrase his translation in the light of actual knowledge of the true significance of the terms employed. Anyone who cares to take the trouble to compare the two versions will be astounded to see how slight a remodeling of a paragraph is sufficient to disperse the obstinate {13} obscurity of prejudice, and let loose a fountain and a flood of living light, to kindle the gnarled prose of stolid scholarship into the burgeoning blossom of lyrical flame.”

Chapman’s argument hinges around this connection between the Alamantrah Working and the Dao De Jing, and around identifying the letters in the image as the number 49. Take a look:

It’s not entirely clear whether Alan Chapman had already settled on his interpretation of Crowley’s picture as being a portrait of Lao Tzu before he attended the LAM workshop with Staley in 2007 or whether his experiences there were instrumental in the development of his thesis. Whatever the case, ‘Oriental’ teachers and sages are clearly a big part of the whole milieu of Crowley’s image and all the connections Staley and Chapman have made certainly make reasonable historical and esoteric sense. The 49 connections are fun, and perhaps Crowley intended for his version of the Tibetan word lam to look like that number. Anything is possible, I cannot say. Still, I am struck by the fact that it’s been over a century since Crowley published his LAM picture and even some of the people closest to the mystery have still not definitively confirmed that Crowley simply wrote out in Tibetan letters the Tibetan word he was riffing on. Given how very accessible even some of the most obscure and esoteric practices of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism are today, it boggles my big swollen, egg-shaped head to see a well-read occultist in 2009 refer to Tibetan letters, a real language spoken and written by millions of actual people on earth, as a ‘pseudo-oriental script’.

Indeed, there is an almost cagey quality to discussions of Crowley’s Tibetan lettering, as if simply accepting that these are in fact letters of a real, intelligible language would somehow deflate the cachet and mysteriousness of the whole phenomenon, would resolve it in a way that no longer lends itself to enjoyable flights of mystical fancy. Here’s one example of what I’m talking about. Danny Carey, the drummer from the American prog rock band TOOL (another evocative capitalization for you), is also an occultist. He has his own LAM inspired T-shirt for so-called ‘LAManauts’, which you can see below:

In a post on TOOL’s Facebook page from four years ago advertising the shirt’s reissue, we see the sort of almost willful indecisiveness around the Tibetan letters in the image that I’m talking about (with Crowley’s more inexpert approximation of Tibetan lettering in gold superimposed over a more correctly rendered purple digital lam ལམ་):

Senzar is the maybe Sanskrit, maybe Tibetan, maybe Atlantean language of the adepts which Blavatsky claimed her ‘Books of Dzyan’ were written in. She seems to have been the only person who ever heard about this language or these texts, which she claimed to have decoded to produce her esoteric treatises. Zhang-zhung meanwhile is an actual, historically attested language hailing from the ancient Zhang-zhung civilization of Western Tibet. Here, even as enthusiasts recognize Crowley’s inclusion of actual Tibetan letters in his drawing, they pull back, wanting to keep things in a less decided, space, one more amenable to occult speculation (see here as a bonus, a TOOL song about doing drugs and having an unplanned encounter with an extraterrestrial guru who imparts spiritual messages of great cosmic import, but you then forget what those messages are and shit your bed instead)

Since I am a Tibetan translator and have one or more feet/tentacles in Western occult goings-on, I feel like it’s worth throwing my hat into the ring here. Now, I’m not interested in yucking anyone’s magical, Personal Gnosis yum – if LAM as alien/Crowleyan self-portrait/Lao Tzu opens ‘gateways’ for practitioners, far from me to try to shut those gateways down or to throw toilet paper and eggs (ha! EGGS!) at them. Still, it does feel like this is yet one more case of Tibetan erasure and alienation by Western esotericists. Not only is the presence of Tibetan in Crowley’s portrait routinely denied or downplayed, but somewhat ironically or maybe not ironically at all, Crowley’s Tibetan alien ends up getting Sinicized. Granted, there isn’t a whole lot of ‘traditional’ Indian or Tibetan Buddhism or Tibetan voices in Blavatasky’s Voice of the Silence, or much traditional Daoism in Crowley’s self-admittedly Hermetic Qabalicized translation of Lao Tzu’s text. Still, it feels a little sad to me that in the one small instance where a prominent Western occultist went to the trouble to present actual Tibetan source material – even just one syllable of it! – it’s been mostly erased or ignored.

Crowley’s caption in his frontispiece seems like it wants to say something about the relationship between spiritual guides on the Path – Gods, gurus, lamas – and the Path itself, lam. In the interest of re-centering Tibet and Tibetan in Crowley’s picture then, let’s look at how the word lama has been parsed by Tibetan speakers, and how Tibetan etymologies for the word address this question of the relationship between the guide on the path and the path itself.

As mentioned, the Tibetan word lama is a translation, Tibetans’ standard way of rendering the Sanskrit term guru in their own language. Tibetan translators have historically emphasized original neologisms over and above mere transliterations of foreign technical terms, and lama is no exception (that said Tibetans do use the transliteration གུ་རུ་ guru when using the word Guru as title). The more general Tibetan word lama has two syllables and components, la and ma, which are written bla and ma in Tibetan:

བླ་མ།

So, if lama doesn’t actually mean ‘treader of the Path’ what does it mean? One of the most common etymologies given for the Sanskrit word guru is that it means ‘heavy’. The guru or teacher is by definition someone who is heavy with knowledge, skills, and positive qualities. A guru necessarily carries a heavier weight of these things and the student or disciple is by comparison a lightweight: someone who is seeking to cultivate, accumulate, or realize these qualities, who needs the ‘heavier’ teacher’s help to do so. The Sanskrit ‘guru’ is cognate with the Latin gravitas (both words have the same Indo-European root) – the guru is someone whose qualities and cultivation lend them weight, authority, seriousness, dignity. There are other popular etymologies for the Sanskrit word guru. A common one correlates the first syllable gu with the darkness of ignorance and the second syllable ru with the fire or light that dispels or vanquishes that darkness. This is a widely cited etymology, despite not really being borne out by purely linguistic or historical facts (traditional Indian sources can be as creative, interpretive, lateral, and ahistorical as Western occultist ones). In any case, Tibetan translators chose not to carry over these Sanskrit associations into their Tibetan translation of the word guru.

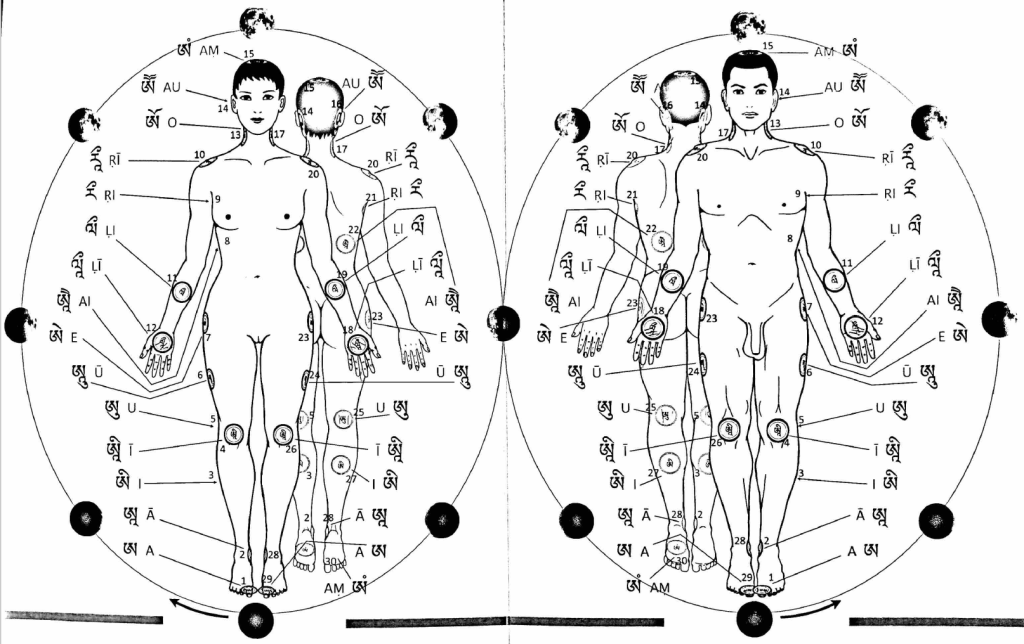

The first syllable of lama, bla, la, is a complex indigenous Tibetan concept, which predates the arrival of Buddhism in Tibet. La refers to a very important kind of ‘soul’ or vital ‘soul-force’, which is described and is a matter of concern in a number of different fields: in Tibetan astrology, divination, human and animal medicine, sexual cultivation, tantric ritual healing, funerary procedures, and everyday human life. La is often said to wander (བླ་འཁྱམས་པ, la khyampa) and it ebbs and flows for various reasons. As a very refined, subtle kind of life-force it moves through various ‘stations’ or points (བླ་གནས, la né) in the body in accordance with the lunar cycle and Tibetan physicians avoid inserting acupuncture needles or performing surgeries on points of the body where the la is concentrated at certain times of the month, lest the la get displaced or be injured and adverse effects arise for patients as a result. La can become depleted through stress, poor sleep, and poor diet, get displaced, fragmented, or frightened away by shock, trauma and accidents, and it can be extracted and captured by malicious spirits or sorcerers as well. Individuals as well as entire family or spiritual lineages possess their own la as a partible force, which can be concentrated in ostensibly external objects like precious stones, trees, and other features of the natural landscape (different species of beings have their own བླ་རྡོ la do or ‘la stone’ which magnetizes, secures, and stores la – the la do of humans is turquoise, for example. Think Tibetan horcrux). The Dalai Lamas also have their own བླ་མཚོ་ la tso, ‘la or soul lake’ in Tibet, which is connected with the state protector goddess Pelden Lhamo/Sri Devi and is occasionally used as a giant natural scrying mirror for gleaning clues about future Dalai Lama incarnations (the lake is linked to both the Goddess’ la and the Dalai Lamas’). Individual and lineage la can also appear outside the body, like a double, in animal or human form.

La is strongly connected with overall personal integrity and vitality, with mental, physical and sexual well-being, immunity, vigor, and resilience. Astrologers and doctors track how la ebbs and flows for different individuals across the years, months, weeks, and days. From a more medical perspective, la is said to be the most refined or pure distillation of ingested food and the bodily fluids and tissues progressively formed from this. La is understood to be a support for the various other life-force energies, the ཚེ་ tsé – ‘lifespan’, ‘longevity’ – and the སྲོག་ sok – the vital life-force which actually keeps the body alive or functioning. The la is the very subtle energy which keeps these other vital forces as well as the རྣམ་ཤེས་ namshé or consciousness, in healthy, stable, harmonious alignment. The literal etymological meaning of la is ‘that which is high, that which is above’ (as can be seen in the Tibetan term བླ་ན་མེད་པ་ la na mepa, ‘unexcelled, highest, none higher’, like in Highest Yoga Tantra). La is thus the highest, purest distillation of digested bodily extracts. It is the most important force keeping the powers of longevity, life, and sentience together. Although it itself moves and flows, it exerts a stabilizing influence. When it is secure and consolidated within the body it keeps a person happy, healthy, and strong. When it is scattered, diffuse, lost, or wandering, vitality, joy, and resilience wane and mental, physical, and emotional volatility and instability increase. In the medical context, the la is said to reside at the wrist margin under the pinkie finger, at the ulnar artery. Doctors feel this point to glean information about the state of patients’ la. The la travels out of the body through an energetic channel that runs through the base and tips of the ring fingers and toes. Sealing the base of the ring fingers and toes with rings, ritual hand gestures or thread is a traditional way to protect the la from seeping or wandering out of the body or from being stolen by spirits. If the la is fully displaced from the body, death follows.

In Sowa Rigpa or Tibetan Traditional Medicine, the nutrients from ingested foods and drinks are extracted through digestion. The pure or clear parts of digested substances become the blood, the pure or clear parts of which become the muscle tissue, the pure extracts of which in turn become fat, bone, bone marrow, and then reproductive cells or essences. The subsequent pure extract of these reproductive essences is called the མདངས་ dang or ‘radiance, healthy glow’ (ojas in Sanskrit). Our individual la is an even more subtle distillation of this dang or ojas, a kind of vital aura. One traditional analogy uses the image of a peeled clove of fresh garlic placed in a bowl to explain la: the bowl is our physical body, the garlic clove is our consciousness and the smell of the garlic which clings to the bowl and the surrounding space, even after the clove is removed from the bowl, is the la. La is associated with our physical body but goes beyond it. It secures our consciousness but can linger behind, close to the body even after a person has died and their consciousness has moved on. La can take on the image of a deceased person after death and may hang around the grave, cremation site, or the place where a person lived, and may cling to their belongings, and so on. In addition to stealing portions of the la of the living, spirits can also wear a deceased people’s la like clothing, or as a disguise, to impersonate them.

Texts often describe the la as a མ་མ་ mama, a ‘nanny’ or ‘nursemaid’ for the sok life-force. In ancient pre-Buddhist Tibet, ritual specialists would perform ceremonies to ‘call or hook back’ the wandering, scattered, or stolen la of ailing patients, whose la might be trapped or lost in the past, present, or future, in all possible dimensions or realms. These བླ་འགུགས་ languk or ‘la hooking/summoning’ rituals are still performed today by Buddhist and Bönpo ritual specialists. There is also a special kind of ‘massage’ or sensitizing touch which can be coupled with visualization and mantra recitation to gently pull la back into the body (Typhonian OTO officionados may be interested to note that this practice, which my Tibetan teacher promotes and calls La massage, seems to be directly connected to the same Indian traditions which inform Grant’s sex magick kala practices, but that’s is a topic for another post, I think).

The first syllable of the Tibetan word lama conjures all of the above associations. Here’s part of the Monlam Tibetan-Tibetan dictionary, one of the most thorough and authoritative Tibetan language dictionaries’, entry for the noun la (my quick and rough translation). It makes clear how much la is a unifying concept:

1. Sorig (Tibetan medicine) term – In the middle of the physical body is the location of the mantric syllable of the purest wind element, which is the ten or interdependent support for the namshé or consciousness, this is the sok or ‘life force’. The duration or time aspect of this location is the tsé or longevity. The mobile or projective aspect of these which accompanies the sem (mind/consciousness) is what is designated as the la.

2. The natural form, shape, or image (rang zuk) of the namshé (consciousness) or alternatively, the unifying or integrating aspect of the loong or vital-wind energy of the pure distillates (the nutrients, bodily tissues and fluids) which support the tsé and sok forces, the tiglé (bindu or ‘drops’, nuclei of consciousness), and the namshé

3. A specific term for the sok. As is stated in the text ‘Clarifying the Meaning of Necessary Medical Terminology’ composed by the 18th century medical authority Deumar Geshé Tenzin Puntsok, “la refers to the tsé, longevity, lifespan, to the drö, vital heat, to all those things which are an interdependent support for the namshé or consciousness.”

4. (A shorthand for) damchen la do, the la or soul-stone of oath-bound protector deities (i.e. stones used in rituals to consolidate protectors’ powers and bind them to human initiates)…

The second syllable of lama, མ ma, can be understood in three main ways. As a standalone word ma can function as a negation, meaning ‘not, is not’. It is also the feminine, feminizing syllable par excellence, since it is a contraction of ཨ་མ ama, ‘mother’, and མ་མ mama, ‘nursemaid’. It also functions as a simple suffix for many common nouns -ma, with the implied meaning of ‘the basis for x, foundation or root of x’. Some commentators read the first syllable as meaning ‘high, highest’ and the second as ‘not, isn’t’, giving the meaning of ‘none higher, none more refined or sublime’. Tibetan-Tibetan dictionaries often gloss this in terms of བཀའ་དྲིན་ kadrin or ‘kindness’. In Tibetan understanding, there is no one in the context of worldly life, there is no one you owe a higher debt of gratitude to, who has done you a greater kindness than your parents. It is they who allowed you to be born and to access the great possibilities of this existence. Your mother in particular, is the ‘kindest of all’ by default. In the Tibetan sense of it, it doesn’t really matter how good or bad your mother was at parenting. If you are alive right now, you owe her a very weighty debt of gratitude indeed. The lama then, the spiritual guide, the person who ལམ་སྟོན་པ་ lam tönpa, ‘who shows or points out the way or path’ (i.e. the way to realizing your own Buddha or Guru nature for yourself, to ultimately liberating yourself from suffering and ignorance) is a second, higher order parent. In Tibetan Buddhist societies, initiating lamas are regularly described as spiritual mothers and fathers, and this particular etymological reading understands them to be the parent, educator, and guide, the ones who help us grow up and become independent, who are even more kind than our worldly parents, because it is they who shows us the way out of conditioned existence and suffering entirely.

Alternatively, if we read the first syllable of lama as the flighty, subtle, vital la soul force and the second syllable as ma, mother or nursemaid, the lama is the one who is like a protective mother to our soul, or most subtle being, a nursemaid who looks down on us from on high and protects and guides us like a loving parent.

So, there you have it. A more Tibetan-centric explanation of the etymology of the word lama, one in which the idea of lam or Path isn’t quite central. A part of me wonders what Crowley would have made of this Tibetan etymology for lama if he had been privy to it, whether he would have engaged with it and found a way to incorporate it into his grand esoteric synthesis. It is, after all, so incredibly layered and rich. Given how much overlap there is between Western occultism, magic, and Tibetan Vajrayana these days and how much time has passed since Crowley published his commentary to Blavatsky’s text, it’s surprising to me how consistently occultists continue to misidentify the Tibetan letters in Crowley’s picture and to repeat his erroneous etymology of lama. Ultimately, it’s probably safe to say that authentic, academically peer-reviewed historicizations of words and practices are not really of primary importance in the Theosophical and post-Theosophical new religious movement terrain we’ve been traversing here. Creative re-interpreting of primary, secondary, tertiary etc. sources is not only excusable in this context, but is regarded as an actual path to gnosis. In his 1992 book, Hekate’s Foundation, Kenneth Grant takes us on a dizzying journey of gematric reasoning, to explain how the word LAMA relates to Western occultists’ understandings of Haitian loa (deities or spiritual principles) and post-Crowley developments in Crowley’s religion of Thelema. “It is surely significant,” Grant says:

“…the word loa is one less than LAMAL, 102, a palindrome expressing the true cult of LAM as the transmitter to AL (Existence) of the vibrations of LA (Non-Existence) via MA, the formula of the daughter, and the key to the Aeon of Maat. Note also that 102 is the number of QB, the root of “Kaaba”? which derives from the Egyptian Kabh, the ‘vase of

the libation’, i.e., the Graal of Babalon. The vehicle of Babalon is Nu Isis. Nu (56) + Mu (46) = 102. The loa or ‘law’ is thus a combination of the aeons of Horus and of Maat concentrated in the Current of Lam, its terrestrial intermediary.”

Clearly, this is not a space where Tibetan Studies expertise is especially wanted, needed, or relevant. Grant has it all covered by himself, and necessarily must follow his own weird and spooky logics. Overall, I think what I find most striking about LAM in all its iterations is just that, it’s incredible and audacious generativity. A small drawing Crowley did which he didn’t comment on much in his life, has managed to give birth to an entire new religious movement, however modest, has inspired viral memes and videos, band merch and a hundred frustrated back-and-forths on Thelemic Reddit. Ambivalence around Crowley’s picture and letters allows them to remain unsited and malleable. Random occurrences and errors, ‘simple’ explanations open up into grander vistas, like when mystically-inclined rabbis write esoteric treatises on why the Torah begins with the second letter of the Hebrew alphabet and NOT THE FIRST, or vigorously and beautifully defend undeniable typos in sacred texts. LAM is nothing if not an unfolding Path. I suppose what remains to be seen is how much potential or need there is for Tibetan Studies, Tibetans, or Tibetan Buddhists to speak alongside or back to occultists’ interpretations.